African Slave Trade Practices

During the 18th century, Britain was a major participant in the African slave trade, notwithstanding the inconsistency of its citizens trumpeting about the freedom available in the homeland. In the first part of the 18th century, Britain sold about 12,000 slaves per year in the New World (39% market share); during the last 80 years of that century the number increased to 23,000 per year (60% market share).14 In one estimate, the ratios of males to females transported varies from a 60/40 split to a 68/32 split.15 There is also some evidence that price ratio between men and women transported in the Atlantic slave trade was about equal.16

The area encompassed within the Blight of Biafra supplied more than 326,000 slaves to the transatlantic trade between 1780 and 1800 and accounted for over one-fifth of all slave exports in the period. Over 85 per cent of the Africans exported from the Bight of Biafra between 1740 and 1807 were carried in British vessels and the region was of particular importance to Liverpool traders.17

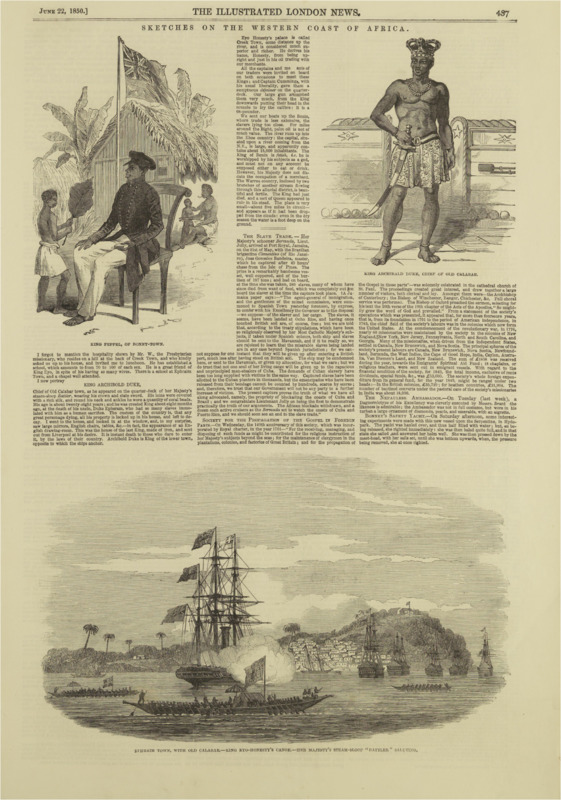

Most of the slaves acquired by the British were sold to them by African indigenous merchants in coastal ports; primarily in Old Calabar and then later in Bonny (both located in the Blight of Biafra). Such acquisitions were usually accomplished through daily sales in small quantities over an extended period of time (sometimes more than a month18 ) using complex market and delivery networks in the interior of West Africa, then gathering them together on the coast where they were exchanged for an assortment of trade goods. Trade networks and military campaigns in the West and West Central African interior determined the flow of enslaved people to the coast in terms of both quantity and direction.19 Most slaves originated as war captives.20 Others were kidnapped, some were sold to ward off starvation, taken for payment of a debt, or to be falsely accused of some crime; still others were born into slavery.21

Antera Duke, for example, was one of 49 Old Calabar merchants who sold slaves and other commodities to the Liverpool ship Dobson between July 1769 and January 1770.22 Excerpts from the Duke and Irving materials confirm that practice. For example, a footnote annotating Duke’s diary entry for January 30, 1785 argues that most of the slaves sold by Efke were purchased by them from towns in the interior because only a single diary entry describes a raid where the Efke themselves captured person to be sold into slavery. The African destinations mentioned by Irving in his letters included some of the most important trading locations for British ships in the late eighteenth century. All of the voyages in which he participated between 1783 and 1788 obtained slaves in the Bight of Biafra.

Another important aspect was that the ability of the captain (or surgeon) to negotiate a favorable rate of exchange for these trade goods; central to the financial success of the voyage. African slaves were typically exchanged for textiles, copper, brass and pewter goods, personal luxury goods, containers, beads, guns, gunpowder, luxury goods and liquor; of which textiles and metals were normally the most important commodities of exchange. Currency and precious metals were not generally used used for payment.23 But cowery shells (a form of currency in some cultures) were also sometimes used for payment. There was little differential between the prices paid for men and women.24 One commentator points out, the merchandise exchanged for slaves included ‘many goods which were relatively high in quality, thereby disproving the myth that Africa got virtually nothing for the export of ‘its sons and daughters’.25 At times, slave ship captains also negotiated with other Europeans in Africa, exchanging merchandise among each other.26

In the New World, slaves were mainly traded in exchange for sugar and other agricultural goods,27 which were ultimately sold in Britain for cash or exchanged for other goods that could be traded in Africa.

______________

14 Colly, Britons: Forging the Nation 1707-1837, Page 352

15 Eltis, David. The Rise of African Slavery in the Americas, page 287

16 Eltis, David. The Rise of African Slavery in the Americas, page 293

17 Schwarz, Slave Captain : The Career of James Irving in the Liverpool Slave Trade, Page 20

18 Irving’s ship was in Old Calabar for three months while purchasing slaves.

19 Ruderman. “Intra-European Trade in Atlantic Africa and the African Atlantic”, Page 215

20 Oliver, The African Experience: Major Themes in African History from Earliest Times to the Present. Page 125

21 Zoellner, Island on Fire: The Revolt that Ended Slavery in the British Empire, Page 57

22 Schwarz, Slave Captain : The Career of James Irving in the Liverpool Slave Trade, Page 24

23 Eltis, David. The Rise of African Slavery in the Americas, Page 300

24 Eltis, David. The Rise of African Slavery in the Americas, Page 293

25 Schwarz, Slave Captain : The Career of James Irving in the Liverpool Slave Trade, Page 26

26 Ruderman. “Intra-European Trade in Atlantic Africa and the African Atlantic”, Page 214

27 Eltis, David. The Rise of African Slavery in the Americas, Page 305