Anniversary Gifts

American made silver:

In the early 19th century, American silversmiths developed their own style, moving beyond their previously trained British counterparts. The tradesmen of the new United States distanced their designs from the British goods of the eighteenth century. The styles became “bolder, more substantial, and confident.”[1]

This confidence in design, also represented the confidence in the establishment of the United States. By providing an American made good for an anniversary, Elizabeth explicitly highlighted that she believed the newly married couples, or new parents, to build their lives with patriotism as its foundation.

[1] Beth Carver Wees, “Nineteenth-Century American Silver,” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, (Department of American Decorative Arts, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004).

Weddings:

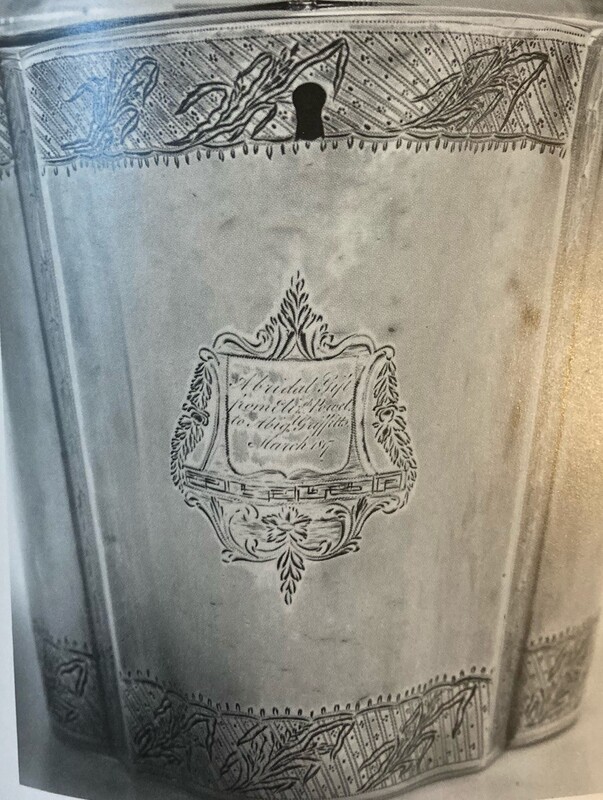

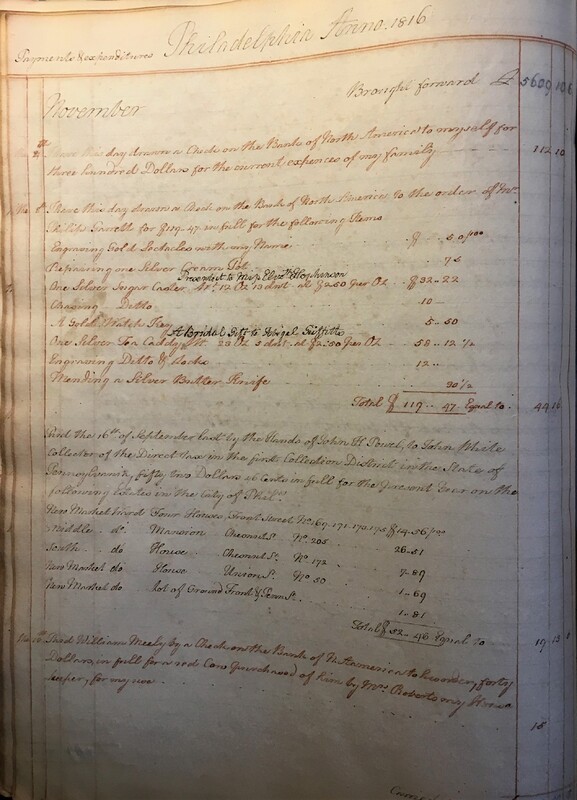

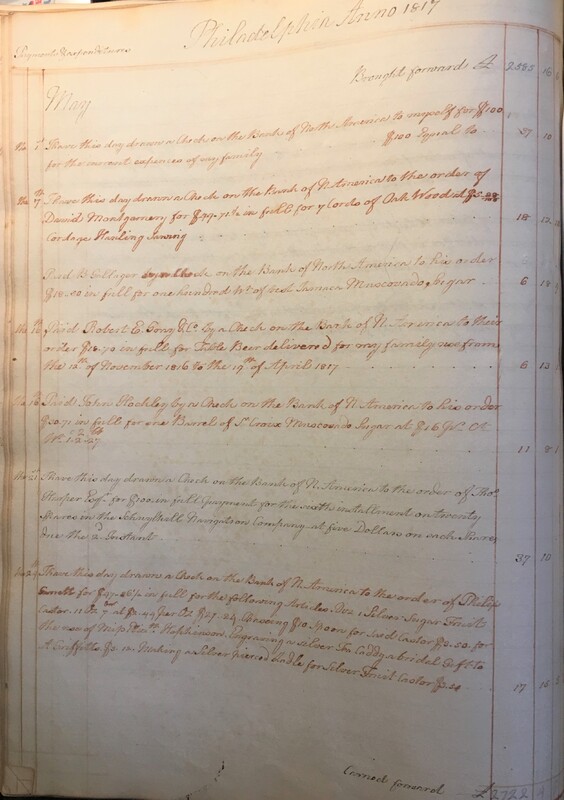

Silver Tea Caddy

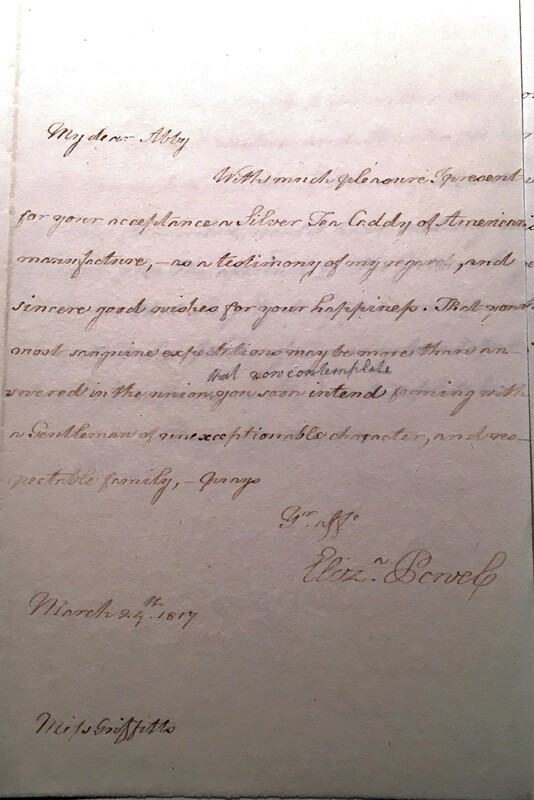

Recipient: Abigail Griffitts (1791-1871)

Abigail Griffits was the daughter of Elizabeth Powel's sister-in-law, Abigail Powel Griffitts. The Griffitts family were Quakers, and while they were high ranking in Philadelphia society, they did not have the same reputation as the Powels. In giving this tea caddy, Elizabeth encouraged her great niece to emulate the genteel status of her Aunt and Uncle, thereby her to the family legacy.[1]

In choosing something related to tea drinking, Elizabeth encouraged the new bride to develop a social network by performing one of the most foundational rituals for developing a social network. “The correct staging of the drinking, and the fashion dictating the manner of serving,” that highlighted the true station of the hostess.[2] The tea caddy that the new bride had access to the “luxury commodity,” of imported tea.

The “presentation engraving,” establishing a permanent connection between the giver and the receiver.[3] For as long as the receiver used the present, especially in the evolution of a marriage, Elizabeth’s name would be associated with it. As this was a gift to a family member, Elizabeth likely expected it to travel through the hands of multiple generations after her, always tying back to Elizabeth and her own power.

In the item showcase below, there are three documents related to the purchase and gifting of the tea caddy.

[1] Zara Anishanslin, Portrait of a Woman in Silk: Hidden Histories of the British Atlantic World, (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2016), 214.

[2]Ching-Jung Chen, Tea parties in early Georgian conversation pieces,” The British Art Journal, 10, no. 1 (Spring/Summer 2009),

[3] David B. Warren, Katherine S. Howe, Michael K. Brown, Marks of Achievement: Four Centuries of Presentation Silver, (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1987), 80.

Childbirth:

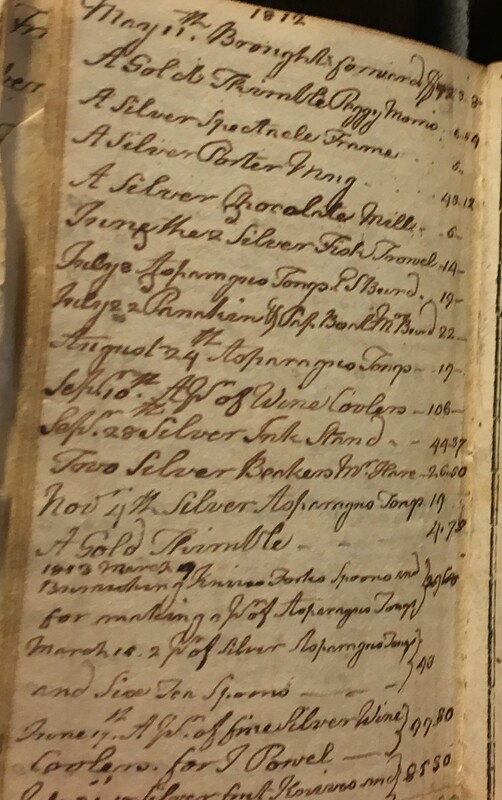

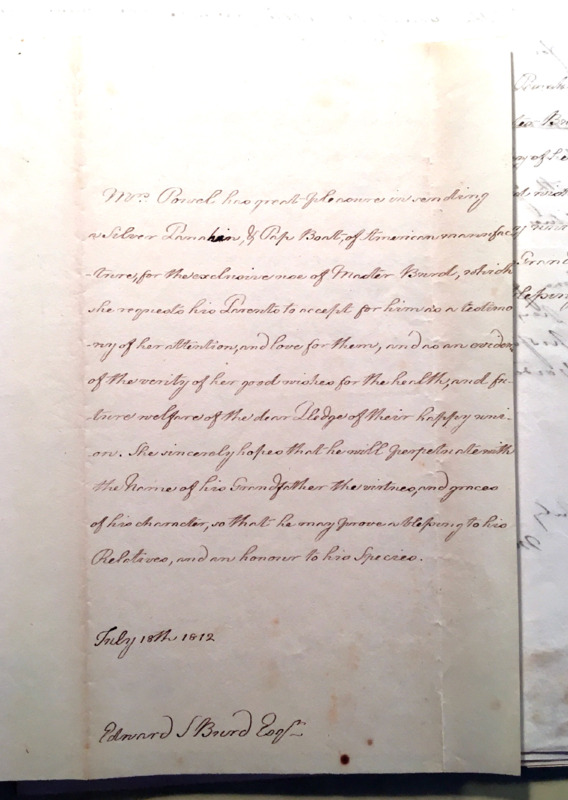

Silver Pap boat and Pannikin Recipients: Eliza Sims Burd (1793-1860), Edward Shippen Burd (1779-1848). Edward Shippen Burd was the grandson of Elizabeth's cousin. Though the family connection was distant, Edward Shippen Burd was one of Elizabeth's closest connections and friends. He served as an executor to her estate and her power of attorney. She frequently gave him silver pieces, and a set of breakfast china, shortly after his marriage in 1810. This gift of a Pap Boat and Pannikin, were for the Burds’ second son, Edward Burd. Their first son died in infancy the year prior. Unfortunately, this son would pass away just over a month later. Elizabeth’s gift, as she wrote, signified her “good wishes for the health, and future welfare of the dear Pledge of their happy union.”[1] Elizabeth likely acknowledged this based on their loss of a son the year prior. The gifts, though sent to Edward S. Burd, are listed in Elizabeth's almanac as being specifically to "Mrs. Burd." A pap boat and pannikin represent nourishment for the new baby and the new mother. A pap boat is an early form of a bottle, and an alternative for breastfeeding.[2] In acknowledging the alternative for breastfeeding. A Pannikin, sometimes referred to as a child’s mug, represented the nourishment of the child as they got older.

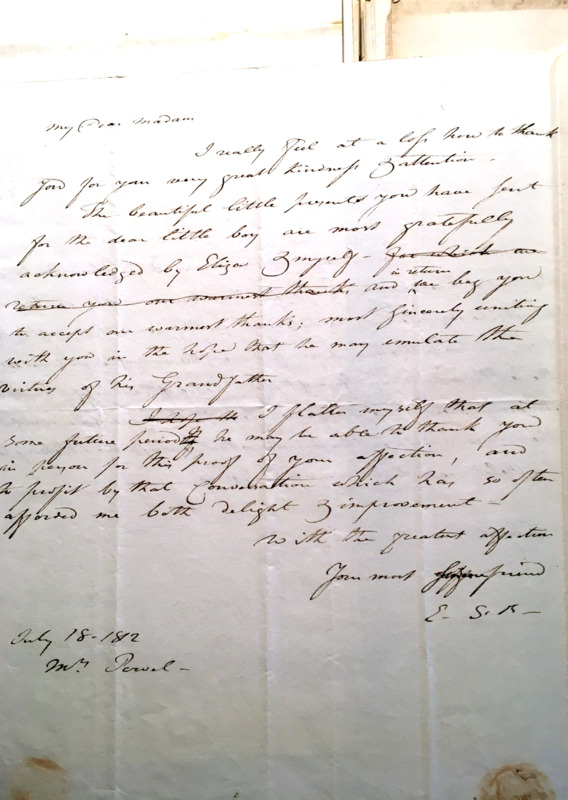

In Edward S. Burd’s response, he writes that he hopes his son, “at some future period he may be able to thank you in person for this proof of your affection, and to profit by that Conversation which has so often afforded me both delight & improvement.”[3] This idea acknowledges how the actual gift itself may not be as important as the “cultural and social interaction,” it may bring within the family network.[4]

In the item showcase below, there are three documents related to the purchase and gifting of the pap boat and pannikin.

[1] "Elizabeth Willing Powel to Edward Shippen Burd, 18 July 1812," Series 3. Elizabeth Powel, Powel Family Papers (1582), Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

[2] Sarah Fox, “An Eighteenth Century Pap Boat: Breastfeeding, Pride & Maternal Love,” Emotional Objects: Touching Emotions in History, (Foundling Museum: 2014).

[3] "Edward Shippen Burd to Elizabeth Willing Powel, 18 July 1812," Series 3. Elizabeth Powel, Powel Family Papers (1582), Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

[4] Vickery, Amanda, The Gentleman’s Daughter: Women’s Lives in Georgian England, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), 222-223.