Enhancing Physical Appearance

Gifts of physical enhancement, helped provide the gift giver to give the recipient a way to have their body present power. This power could be shown through outward adornments, perfect posture, or handmade material goods.

Outward ornaments

Watch String

Recipient: Bushrod Washington (1762-1829)

Bushrod Washington, the nephew of George Washington, was one of Elizabeth’s earliest favorites. He spent a year in Philadelphia studying law, and frequently mentioned in letters home to his mother how much he adored the Powels, especially Elizabeth. He wrote that he would “send the most happy Hours in that agreeable family – I at once find Instruction and entertainment, and after a day’s Study, it proves an agreeable relaxation.”[1] The close relationship between Bushrod and Elizabeth formed out of Elizabeth’s loss of her own children.

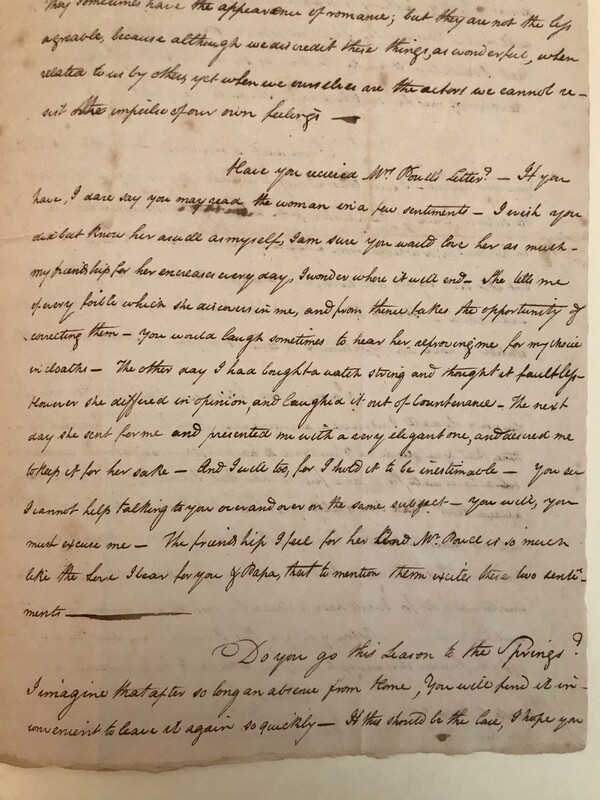

In the case of the watch string, it came out of one of many times she “reproved” Bushrod for his choice of clothes. He wrote to his mother about the moment she gave him the string:

“She tells me of every foible which she discovers in me, and from thence takes the opportunity of correcting them – You would laugh sometimes to hear her reproving me for my choice in cloaths – The other day I had bought a watch string and thought it faultless. However, she differed in opinion, and laughed it out of Countenance. – The next day she sent for me and presented me with a very elegant one, and decreed me to keep it for her sake. – And I will, too, for I hold it to be inestimable.”[2]

This string represents the idea that the receiver could consider it as an “intimate token of affection,” as it was worn close to the body.[3] A watch string also represented industrial and intellectual prosperity, as it kept the wearer focused on time. As Bushrod was studying law, and under the watchful eye of his uncle, he needed this type of status boosting gift.

[1] "Bushrod Washington to Hannah Bushrod Washington, 12 April 1783," George Washington National Masonic Memorial.

[2] "Bushrod Washington to Hannah Bushrod Washington, 7 June 1783," George Washington National Masonic Memorial.

[3] Good, Cassandra A. Founding Friendships: Friendships between Men and Women in the Early

Republic. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015, 126-129.

Fashioning the Body

Posture collar/chin piece

Recipients: Eliza Parke Custis Law (1776-1831), Martha Parke Custis Peter (1777-1854), and Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis (1779-1852)

The three recipients of these gifts were the granddaughters of George and Martha Washington. They were the daughters of Martha’s son John Parke Custis, who died in 1781 shortly after the death of his son, George Washington Parke Custis. Eleanor Pare Custis Lewis and George Washington Parke Custis lived with the Washingtons beginning in the 1780s, and all throughout the presidency. Elizabeth was close with both of the grandchildren.

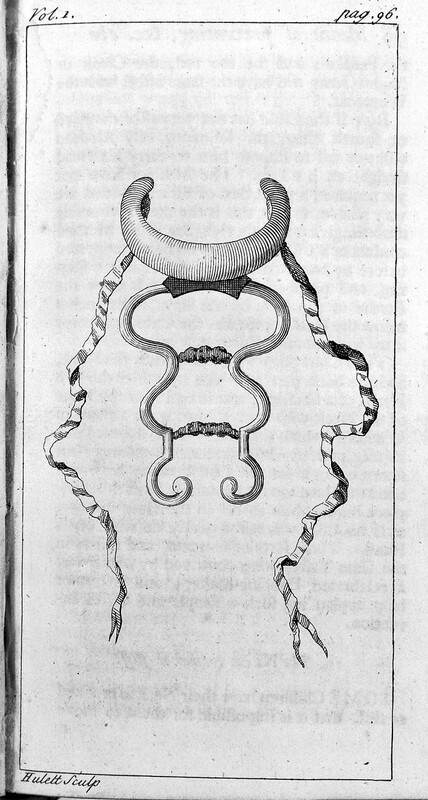

Elizabeth purchased these collars/chin pieces shortly after the Powels’ return to Philadelphia after visiting the Washingtons at Mount Vernon in early October 1787. As young girls, the Custis granddaughters were reaching the stage of necessary lessons in physical appearance. Elizabeth did not send these without previous direction from Martha Washington. Elizabeth viewed these collars as a necessary means to be as healthy and confident as possible. She described her thoughts on the collars in her letter to Martha in November 1787:

“these are… as essential to Health as to Beauty, to hold up the Head & throw back the Shoulders. It expands the Chest & prevents those ridiculous Distortions of the Face & Eyes at which Girls, at a certain Age, frequently fall into from a foolish Bashfullness, or, as the French call it; a mauvaise honte.[1]

She also expressed her distate at another style of collar:

“There are Collars with Backs for the Shoulders; but this is so like putting them in Harness that I reprobate them, as I do all Ligatures on the human Form. Native Grace is superior to all that Art can do; and it is as natural to hold up the Head, & open the Chest, as to lollop the Head in the Bosom & rise the Shoulders to the Ears.”

By providing the easiest, most comfortable of the variety, Elizabeth knew she would still be successful in establishing a proper set of young ladies, but not with any negative connotation. She also knew that these pieces would not be publicly displayed, and that the practice of posture correction was more private, so she made adornments (Ribbon and sashes) for the collars to "be worn over them as a Disguise when the young Ladies are dressed or go without a Vandike."

See Martha Washington's response in the Item showcase below.

[1] Elizabeth Willing Powel to Martha Washington, 30 November 1787, Martha Washington Collection, Mount Vernon Ladies Association.

Self made fashion

Pockets

Recipient: Elizabeth Hopkinson Elizabeth Hopkinson (1800-1891)

Elizabeth was the daughter of Elizabeth’s godson Joseph Hopkinson. The Hopkinson family lived next door to Elizabeth Powel, and seemingly interacted with her quite frequently. In the 18th century, when Elizabeth Powel was a young woman, she would have been a frequent wearer of pockets. These were separate to the actual dresses or skirts women wore, and interchangeable. Women kept their most useful and personal accessories in their pockets throughout the day, such as “thimbles, keys, handkerchiefs, spectacles and coins.”[1]

By the nineteenth century, separate pockets were not as important of an object, as they fell out of fashion with the rise of built in pockets. This is an interesting letter as it shows how Elizabeth interacted with her servants, that she started the set and her "workman" finished them. This "workman" may have been Margaret McIntire, Elizabeth’s longtime mantua-maker and seamstress.

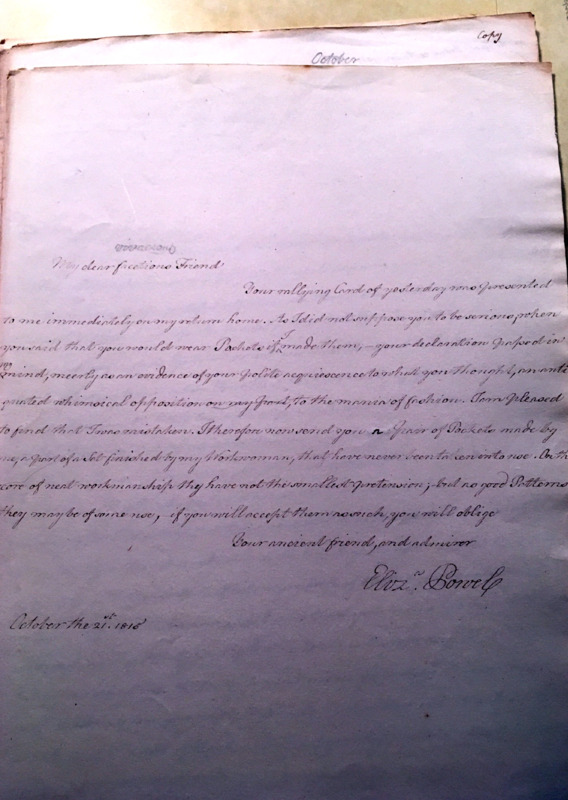

In her letter to Elizabeth Hopkinson, Elizabeth Powel expresses her surprise at her young neighbor desiring a pair made by Elizabeth herself. She sent a pair she made, and explained they would work as good patterns. This encouraged the young woman to make her own, regardless of fashion or taste, it would be good to do an industrious activity: “

As I did not suppose you to be serious, when you said that you would wear Pockets if I made them; - your declaration passed in my mind, merely as an evidence of your polite acquiescence to what you thought an antiquated, whimsical opposition on my part, to the mania of fashion… On the score of neat workmanship they have not the smallest pretension; - but as good Patterns they may be of some use, if you will accept them as such.”[2]

[1] Unknown, (Maker),. ca. 1784, Image: 2007. Pocket (Tie Pocket). Accessories-Women; Carried. Place: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://library.artstor.org/asset/ABROOKLYNIG_10312351074.

[2] “Elizabeth Powel to Elizabeth Hopkinson, 21 October 1815,” Series 3. Elizabeth Powel, Powel Family Papers (1582), Historical Society of Pennsylvania.