Every Dog Has its Day (in Court)

"While most contemporary Western legal systems treat animals as chattels to be acquired, controlled, and disposed of at their owners' pleasure, animals have historically been treated as partial legal persons to allow the legal system to respond to the unpredictable and sometimes fatal harms they cause." - Anila Srivastava, Mean, dangerous, and uncontrollable beasts.

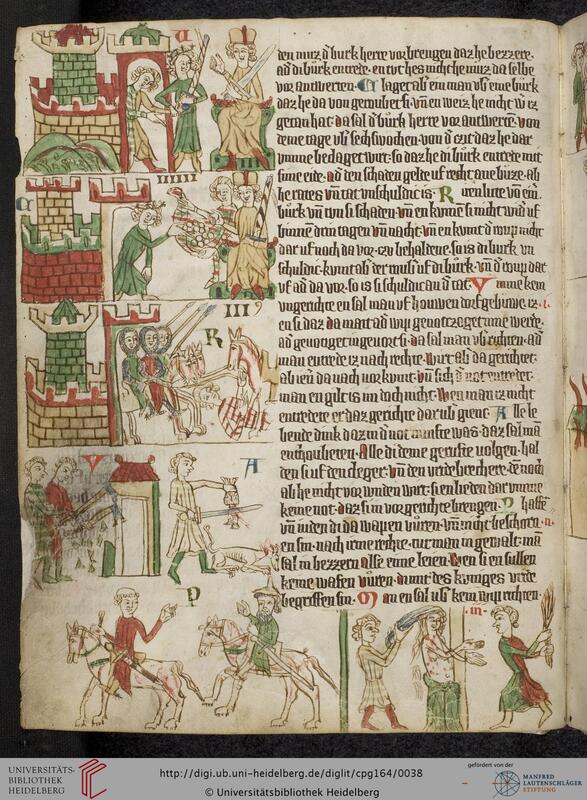

As discussed and exemplified in Establishing Boundaries and Caught in the Act, animals continued to be held to human rule of law as it was believed they were creatures with the intelligence necessary to make decisions. It is alleged that hundreds of animals trials had taken place in England throught the centuries; however, the trials are difficult to distinguish for regular trials as a result of this lack of legal differentiation. The animals in most recorded trials are personified and referenced in terms that are neutral (such as offender). Often animals were given identical sentences to their human accomplices, animals that were deemed homicidal were either hung or inverted, whereas crimes of bestiality resulted in burning.[1]

In the late 17th century, a dog was tried in Austria and incarcerated for a year for biting the leg of a local council member. Two centuries later, the English satire Another Ministerial Defeat! The Trial of The Dog for Biting the Noble Lord (potentially inspired by the incarcerated dog) was published by William Hone. The publication mocks long standing English judicial practices that upheld this belief that animals could held to human rule of law. Honesty (the dog) was bound and brought before the court on the accusation of malicious intent to hurt and damage the reputation of an unnamed Noble Lord. The trial was composed of nine jury figures, a prosecutor, and counsel for the defendant. It was reported that Honesty had bit the Noble Lord in his own home, leaving him in critical condition, and then fled the scene of the crime. Honesty’s actions created a “man-hunt” for its capture and the policemen that captured Honesty was promoted for his “vigilant perseverance.”[2]

The odds were stacked heavily against Honesty as it seemed more likely it would soon be facing imprisonment. However, the trial took a dramatic shift as they called a new witness to the stand that offered incriminating evidence against the Noble Lord. The Door-Keeper to the Noble Lord’s home recounts seeing Honesty present at the house; however, Honesty was located on the other side of the house and therefore unable to cause the injuries sustained by the Noble Man. It came to light that the Noble Lord was indeed “mad” and bit himself. Fearing how his peers would react and his reptuation would be negatively impacted, the Noble Lord blamed the injury on Honesty. After the Door-Man’s testimony, more witnesses came forward to collaborate Honesty’s innocence and testify on behalf of Honesty’s character. The final verdict was not guilty.

While the narrative of Honesty was a satire to poke fun and acknowledge England’s history of placing animals on trials, it suggests an acknowledgement of the country’s historically complex relationship with animals; however, it its a signal perhaps new shift in thought concerning aninals. Animal trials were taking place throughout Europe including the time century in which this satire was published, but Hone mocks the idea of placing animals on trial which suggests an ongoing discourse concerning animal conciousness.

[1] Anila Srivastava, "’Mean, Dangerous, and Uncontrollable Beasts’: Mediaeval Animal Trials," In Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal 40, no. 1 (2007): 127-43.

[2] William Hone, Another Ministerial Defeat! The Trial of The Dog for Biting The Noble Lord; with the Whole of the Evidence at Length, (London: Old Bailey, 1817), 6.