Legacy of the Lady

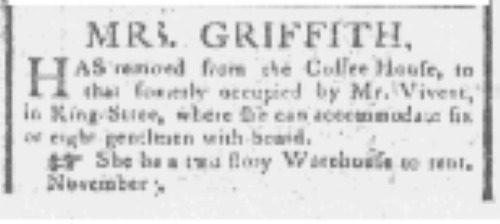

After nearly three and a half years of running the coffeehouse, Hannah decided to hang up her apron in October of 1797. Years after Hannah exited the business, coffeehouses remained integral to merchants in prosperous cities, as we can see by newspaper advertisements of proposals to advocate for the establishment of new coffeehouses. Hannah’s local paper announced her departure and her move to a nearby house on King Street where she would have room to board up to eight tenants. Included at the bottom of the notice was a note that she had a two-story warehouse available to rent.[1] It appears she was doing well on her own, still supporting the younger children, but the paper trail ends here for a while. Then, her name appeared in print once more, allowing future historians one more opportunity for partial examination of this woman.

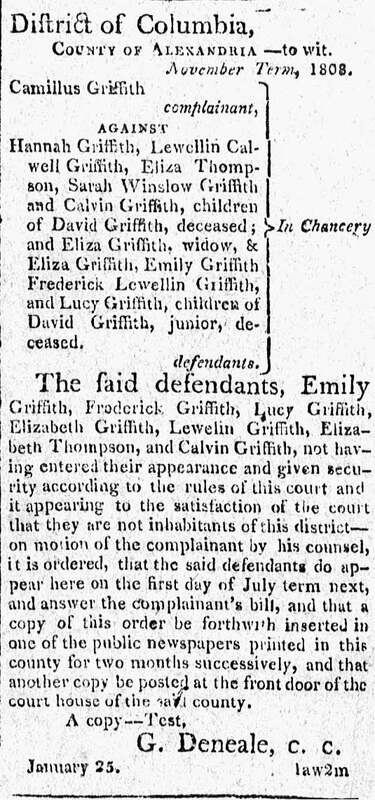

In 1809, her son Camillus sued his own mother, his siblings, and their spouses to gain control of his share of inheritance of those same Kentucky lands mentioned years earlier in Hannah’s petition.[2] It seems Hannah’s well-planned route to selling the land in order to pay her debts did not totally pan out. Unfortunately, Camillus would go on to become a notorious slave-catcher as well. One of his many assignments took him all the way to Massachusetts where he kidnapped and attempted to forcibly transported escaped individuals back to Virginia enslavers. The state of Massachusett's attempt to thwart his efforts resulted in the 1823 landmark case of Commonwealth of Massachusetts vs Camillus Griffith.

Camillus escaped charges for violating the Fourth Amendment’s search and seizure laws, and the court upheld the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, ruling that enslaved individuals were excluded from the legal protection provided by that law—excluded, in fact, from the entirety of Constitutional rights and protections.[3] Thus, Hannah’s name would become associated with this dispicable man. But, was Camillus viewed as dispicable, as disreputable, within his society?

In Hannah and Camillus's world, the business of retrieving escaped persons by force and returning them to a life of bondage was legal and quite profitable. Another son of Hannah's would also benefit financially from the system of slavery as he arranged the transport and sale of enslaved individuals from Maryland south to Virginia. Instead of finding these facts incompatible with the idea of the Griffith family's respectable reputation, it is actually a reflection of the central role that slavery played in American economics. Hannah herself would have profited from the wealthy men who met at her coffeehouse to discuss and settle deals that most certainly were connected in some way to the slave trade.

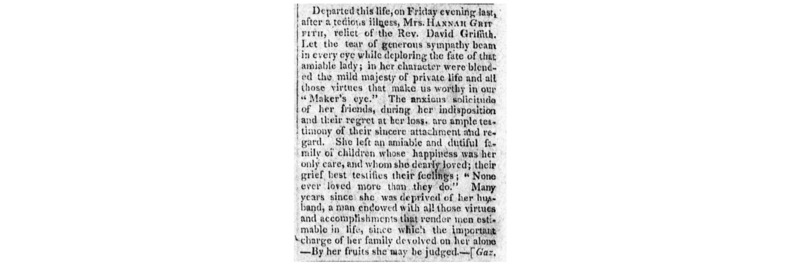

Hannah Colville Griffith died in 1811.[4] The location of her grave is unknown to me at this time, though a tombstone for Eliza Llewellyn Griffith Hoxton—born November 28, 1817, died March 19, 1854—most likely a granddaughter she never met, sits in the cemetery of Hannah’s old Alexandria Church, now known as Christ Church, where she would have walked many times beside her young husband, their two daughters brushing against the flowers blooming in the churchyard, and their six boys contemplating mischief all along the way.

To understand Hannah Griffith’s particular situation better, an analysis of the entire contents of the letters between she and her husband, David, is needed, especially the correspondence during the War years when he served as a surgeon and chaplain while she remained back at their parish home, holding the farm and family together, with her mother-in-law and an ever-increasing number of children under her care. Was she herself directly acquainted with the wives of her husband's celebrated contemporaries? Did she forge her own relationships that would aid her future endeavors? How much of a respectable role was she able to carve out for herself, outside that of being the reverend's wife? Early ecclesiastical scholars provide many excerpts from original documents, though the documents themselves are not yet digitized and I am still in the process of obtaining copies of the original letters and account books. It is hoped that by thorough examination of these documents more details will be revealed regarding Hannah’s social and financial status and connections, as well as specifics regarding any use of enslaved labor or taking in of children as boarders for schooling.

It is tempting to simply award Hannah Griffith praise for her inspiring strength and perseverence. She took on the responsibilities associated with her husband’s debts, eight growing children at home, and a business world that was not known to roll out the red carpet to those of the feminine persuasion. I am not arguing that she be denied any such credit, but one wonders to what degree Hannah was able to rely on the conception of "respectability" to overcome obstacles that may have otherwise been insurmountable. It would be of great use to compare Hannah Griffith’s status and experience in the business world to that of another coffeehouse proprietor in the same general time period and region. Such a probe may help reveal further links between privilege, the perception of achievement, and assumptions of innate superiority that continue to challenge our society to this day.

[1] “Mrs. Griffith has removed,” The Columbian Mirror and Alexandria Gazette (Alexandria: Nov. 9, 1797).

[2] William B. Sprague, ed., Annals of the American Episcopal Pulpit; or, Commemorative Notices of Distinguished American Clergymen of Various Denominations, from the Early Settlement of the Country to the Close of the Year Eighteen Hundred and Fifty-Five, Vol. 5 (New York: R. Carter & Brothers, 1858), 70. (Available through Sabin Americana: History of the Americas, 1500-1926)

[3] “Camillus Griffith complainant, against Hannah Griffith,” Alexandria Gazette (Alexandria: Jan. 25, 1809). Accessed through Readex.com.

[4] Dean Grodzins, “’Slave Law’ versus ‘Lynch Law’ in Boston: Benjamin Robbins Curtis, Theodore Parker, and the Fugitive Slave Crisis, 1850-1855,” Massachusetts Historical Review 12 (2010): 6, 28.

Created by Kristy Huettner, 2020.