Encouraging Patriotism

Patriotic gifts on display

Both the Argand lamp and the asparagus tongs represent the public use of either an American made good, or a good to promote American ideals. The Argand lamp was purchased at a time when the United States was in its infancy, and Elizabeth had all her connections to the political figures of the era. She her power, in this specific case, through her connection with George Washington to help influence the future political discussions. Elizabeth continually purchased American made goods throughout the nineteenth century, for anniversaries and for presents. Both of these gifts are not overly ostentatious, and made for practical use.

Argand lamp

Recipient: George Washington (1731/2-1799)

President George Washington was a close friend of both Elizabeth and her husband Samuel Powel, for nearly 30 years. Elizabeth frequently gave gifts to George Washington, including books, a chair (commissioned and designed by herself) and an argand lamp of this same style. The gifts between George and Elizabeth highlight a political relationship built on “mutually beneficial political gain.”[1]

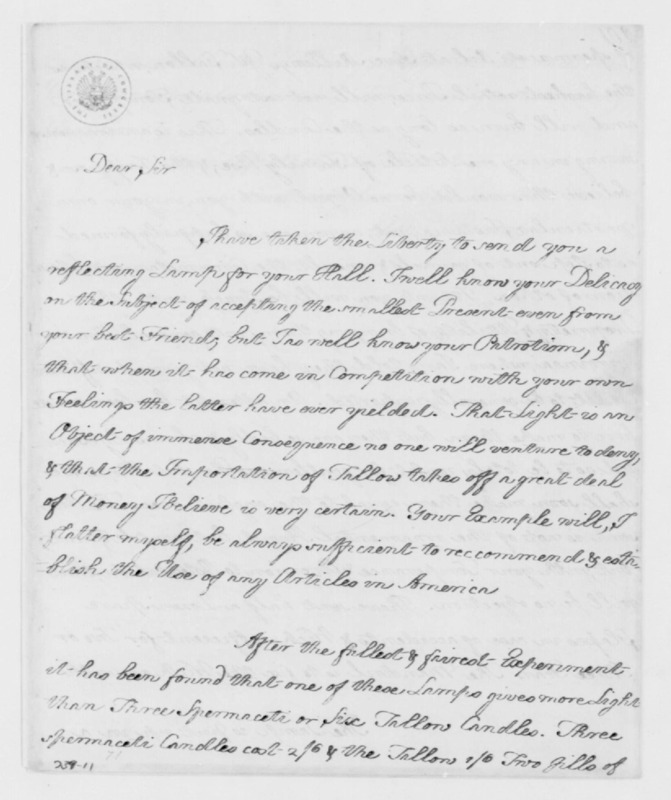

In the 1780s, Argand lamps were a revolutionary new form of lighting, patented in 1780 in France. The design of the argand lamp made it “easier for study and allowed for individuals to read with greater ease.”[2] She acknowledged the lamps importance, and that if he put it in his home on public display, this “…Example will, [I flatter myself] be always sufficient to reccommend & establish the Use of any Articles in America.”[3]

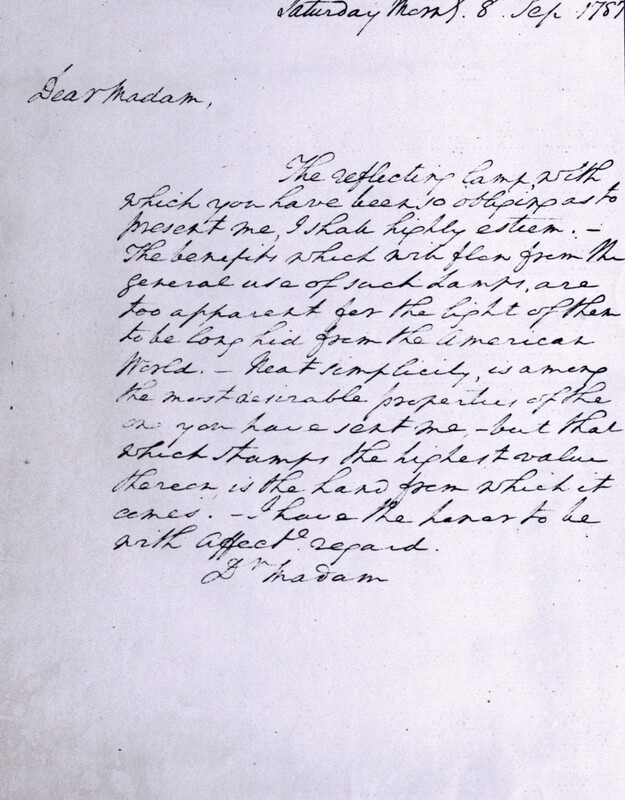

With this, she used Washington as a way to move the intellectual happenings of America forward quickly. The lamp itself was not American made, but Elizabeth’s sentiments were what tied it to the newly forming United States. Her purpose was not to simply provide a fashionable good for the Washington home, as she did not give him a design of “of the ornamental Kind, but simple & neat; but, with your Temperance & Aversion to Ostentation, that will be no objection.” George Washington responded and said that he would “highly esteem the lamp.” He also acknowledged the true sentiment and significance of the gift, that “the benefits which will flow from the general use of such Lamps, are too apparent for the light of them to be long hid from the American World.”[4]

In the item showcase below, there are two documents related to the gifting of the Argand lamp.

[1] Good, Cassandra A. Founding Friendships: Friendships between Men and Women in the Early

Republic. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

[2] Deepanita Ghosh, “Illuminating the Past: Artificial Lighting in America (1610-1930) and a Guide to Lighting Historic House Museums,” (University of Georgia: 2004), 12.

[3] George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Elizabeth Powel to George Washington, September 8. September 8, 1787. Manuscript/Mixed Material.

[4] "George Washington to Elizabeth Powel, 8 September 1787," Photostat Collection, Mount Vernon Ladies Association.

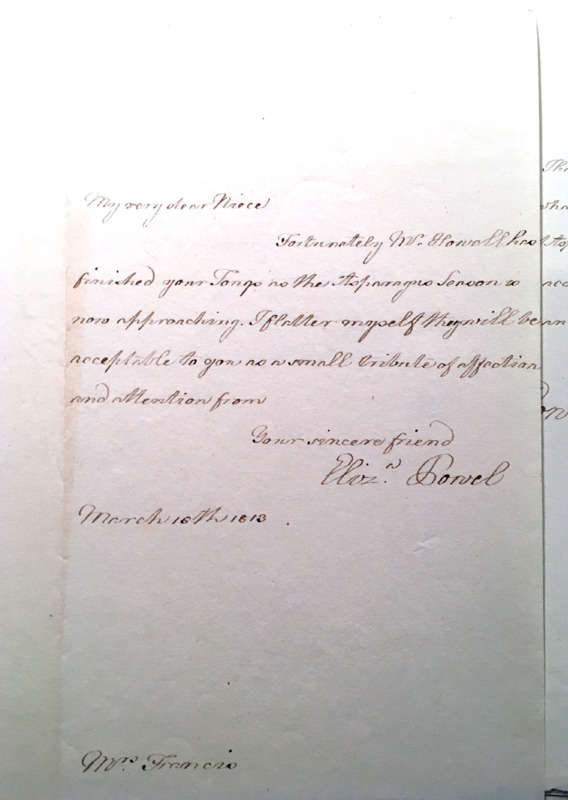

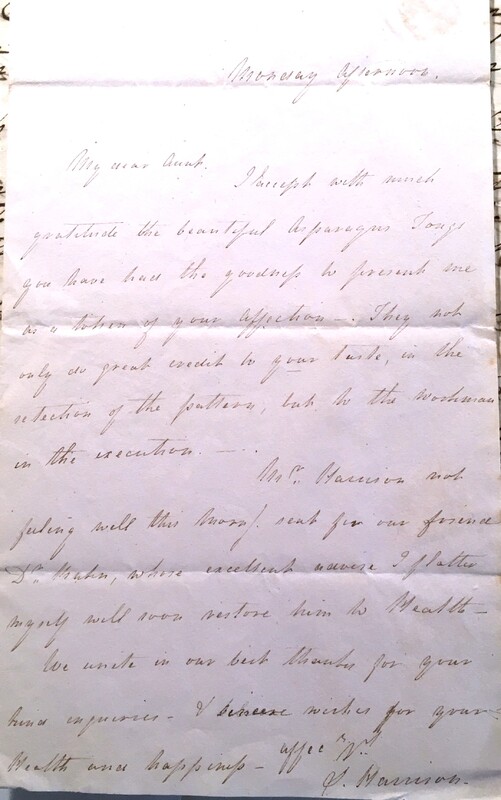

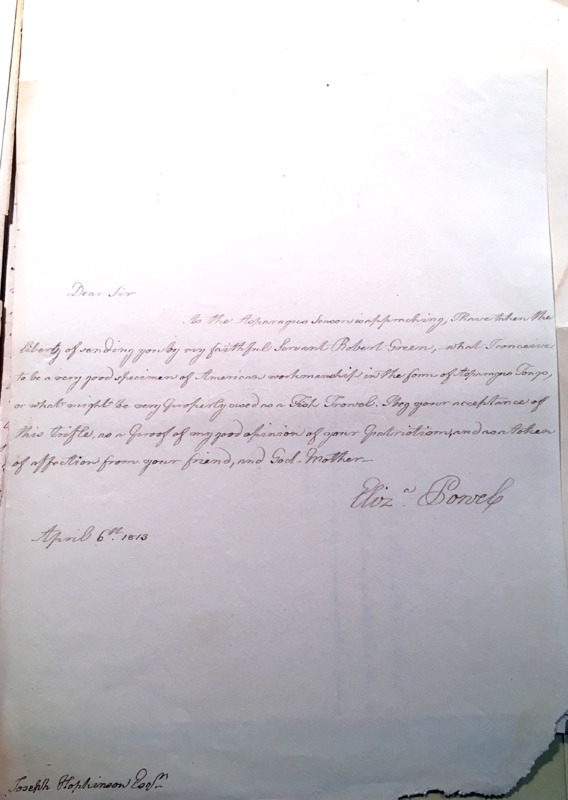

Asparagus Tongs

Recipients: Sophia Francis Harrison (1769-1851), Dorothy Willing Francis (1772-1847), Joseph Hopkinson (1770-1842)

Sophia Francis Harrison and Dorothy Willing Francis were both sister-in-laws and cousins. This highlights the small family networks so common in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Elizabeth corresponded with both young women frequently, and actively encouraged their upward mobility in society.

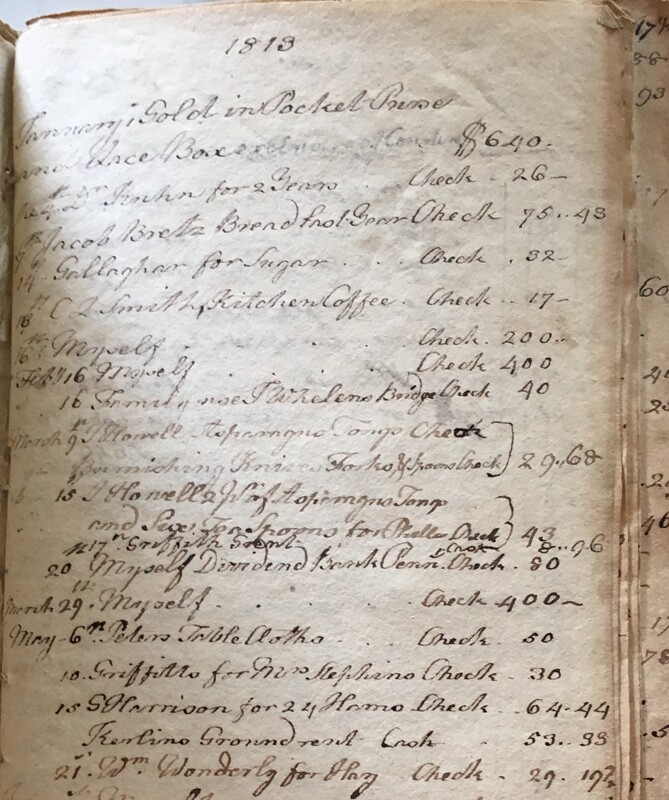

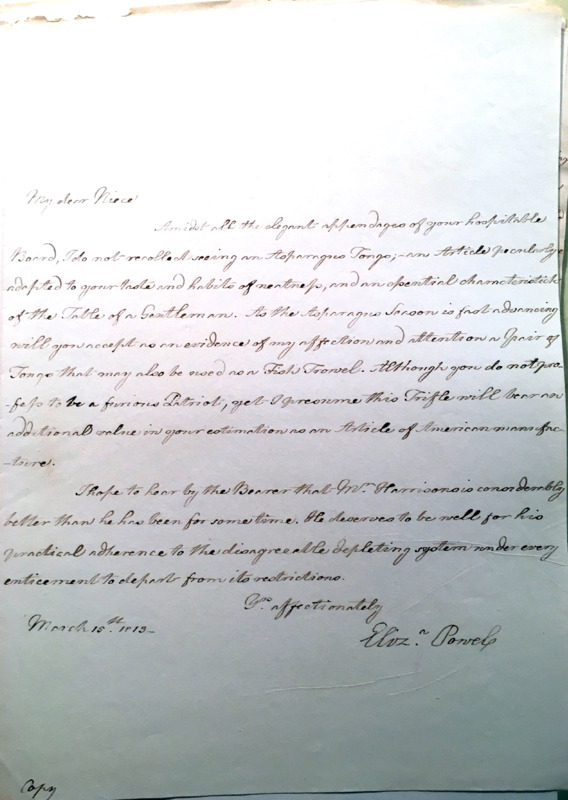

Joseph Hopkinson was the son of Francis Hopkinson, who was close with both Elizabeth Powel and her husband Samuel. Joseph Hopkinson was Elizabeth Powel’s godson, a relationship she took very seriously. Each of these Philadelphians were grown adults, and Elizabeth considered this gift as more of a social gesture of “good will, material aid, and courtesy,” which helped to develop the social structure.[1] In the case of Sophia Harrison, she specficially acknowledges that “Amidst all the elegant appendages of your hospitable Board, I do not recollect seeing an Asparagus Tongs…” and even though “you do not profess to be a furious Patriot…this Trifle will bear an additional value in your estimation as an Article of American manufacture.”[2] As she does with the gifts for anniversaries, Elizabeth is clear to note American manufacture. She also acknowledged that the asparagus tongs could double as a fish trowel, highlighting the usefulness of the piece. Asparagus, though well established in America, was somewhat of a luxury good. Similar to the Argand lamp she gifted to George Washington, there is no particular formal decorative value. The function itself, as well as the presence on the already “hospitable Board,” shows Elizabeth’s desire to elevate the couples to the next level of elite, just from their possessions alone.

In the item showcase below, there are four documents related to the gifting of the asparagus tongs.