Prestigious Pourhouse

With what must have been unimaginable sorrow weighing upon her, Hannah had to push forward and prepare to leave her home as another minister, Reverend Lord Bryan Fairfax, made plans to fill David’s position in the parish. Bryan Fairfax, the 8th Lord Fairfax of Cameron, was content to remain at his own impressive estate. Instead of moving himself into Glebe House, Lord Fairfax allowed the property to become the home of his daughter Elizabeth and her new husband, Hannah's eldest child, David Griffith, Jr. The couple were permitted to remain there during the Reverend Lord Fairfax's service to the parish.

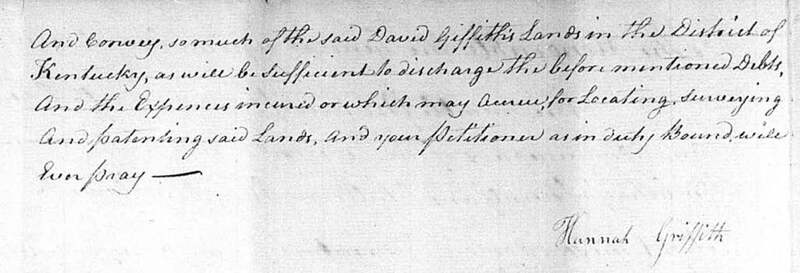

Thus, Hannah left behind her home of the past decade just months after losing her husband. Exactly where she went is unclear, but she still owned properties in Alexandria. Perhaps she squeezed her family into one of them or maybe the ladies of her parish took her and the children under their care for a time. What is apparent is that she expeditiously collected her wits and sorted her affairs, because by October of 1791 she had composed and submitted an eloquent petition to the General Assembly of Virginia asking that she be allowed to sell her husband’s military land grants (instead of dividing them among the her and the children as inheritance) and use the money to pay the family’s crushing debt. The education provided to a young lady in Hannah’s day was often determined by her parents' own levels of learning. Most girls concluded their formal studies after learning to read, though boys were more likely to move on to lessons in the art of writing. It is likely that education was a priority for Hannah and her family due to the artful precision of her penmanship[1], as displayed in the petition. Education would be yet another asset to Hannah in her future endeavors.

In her 1791 petition, Hannah carefully explained the specifics of her debts, including £600 in Virginia currency owed to the executors of Ann Colville, which may have been money borrowed by the couple from Hannah’s mother. Another £840 was owed to a Mr. Thomas Lewis and all she had to work with was the Kentucky land. Of course, she could have sold the property in Alexandria, but she articulated in her petition the reasons why she felt it more beneficial to maintain ownership of that property, as it was likely to increase considerably in value and leasing it would provide immediate income necessary for her and her children’s survival.[2] She also presented the letter written by David shortly before his death, in which he gives power of attorney to a representative, Christopher Greenup, who is instructed specifically, by the same letter, in the methods by which to sell the Kentucky land and settle the debts. The Assembly found Hannah’s request reasonable and approved her petition.

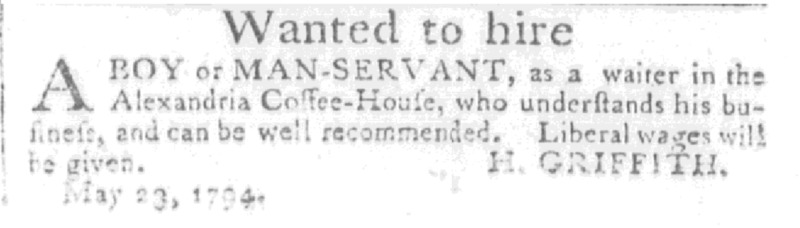

By May 1794, Hannah regained enough footing to lease a handsome building situated on an ideal lot across from Market Square, next to the most luxurious hotel in all of Alexandria and the newly emerging District of Columbia, and she placed an advertisement in the town paper promising “liberal wages” for a waiter.[3] The brick structure she leased had been a tavern, but Hannah envisioned the space as a “Coffee-House,” a sort of social club and reputable space to facilitate discussion and business exchanges among wealthy merchants—which there was no shortage of in the busy port city of Alexandria. Of course, one could also order tea or the warm, frothy, dark chocolate liquid quite often enjoyed by wealthier adults in the morning. The caffeine content of each of these beverages, plus any added lumps of sugar, fueled lively interactions and displayed the wealth of her patrons as each of these items- coffee, tea, chocolate, and sugar- were expensive imports. In addition, coffeehouses typically charged subscription fees, essentially membership dues. Thus, these gathering places enjoyed a customer base that was, or at least considered themselves to be, more refined than that of a tavern or alehouse.

British America's concept of the coffeehouse and its connection to respectability grew from the eminence of London's merchant and exchange coffeehouses, though the institution stretches much farther back, likely being of Turkish origin.[4] America's infatuation with the coffeehouse would never quite match that of England's, though Boston and other centers of United States commerce would construct massive, luxurious facilities that rivaled those of London. Businessmen had enjoyed gathering in coffeehouse like Hannah’s for centuries. In the company of other "respectable" gentlemen, deals were solidified, politics discussed, and news shared, all while sipping the invigorating imported drink that had surpassed tea in popularity and patriotic association.[4]

1 Jennifer Monaghan, “Literacy Instruction and Gender in Colonial New England,” American Quarterly 40, no. 1 (Mar 1988): 19.

2 Hannah Griffith: Petition, Oct. 21, 1791, Petitions Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond.

3 “Wanted to Hire,” advertisement in The Columbian Mirror and Alexandria Gazette (Alexandria: May 24, 1794). Accessed through Readex.com.

[4] Nat Zappiah, “Review Essay: Coffeehouses and Culture,” The Huntington Library Quarterly 70, no. 4 (2007):672-673.

Created by Kristy Huettner, 2020.