A Respectable Option

Although Hannah maintained many of her deceased husband's Alexandria, lots[1] deciding that these were valuable as potential future income, the recently-widowed mother-of-eight’s finances were dire. The Kentucky lands were not selling. Debts were owed. However, the poorhouse was not an imminent threat to Hannah, as it might have been to other women in similar circumstances. Her status as widow of the celebrated Dr. Rev. David Griffith and her eldest son’s recent marriage to Elizabeth Fairfax, daughter of Bryan Fairfax, the 8th Lord Fairfax of Cameron and successor to David Griffith’s position as rector of Fairfax Parrish, afforded Hannah opportunities unavailable to less-revered personas.

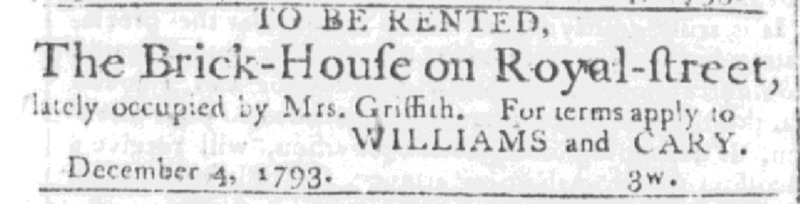

From 1794 to 1797, Hannah Griffith leased one of John Wise’s brick buildings which sat on Royal Street, alongside Market Square, but she did not operate a tavern there as had previous proprietors. Taverns, alehouses, inns, and coffeehouses were all classified as some form of “ordinary” for licensing purposes, and a license was required to serve alcohol- sometimes called tippling, thus the term "tippling house."[2] Even the coffeehouse would have alcoholic options. However, the atmosphere that differentiated each of these establishments relied heavily on the clientele they attracted. Each provided “institutionalized sociability,” but by the end of the eighteenth century, the political importance of taverns was being replaced by buildings in the capital city constructed for the purpose of debating and deciding legislature. Taverns eventually became regarded as less reputable places where drunkenness and debauchery were to be found. Alehouses had never pretended to be much more than a room to drink in, but inns and taverns also supplied news, space for events, meals, and lodging. The emergence of the hotel and its focus upon comfort and luxury during a visitor’s stay, would raise the standards of “institutionalized sociability”[3] and the coffeehouse would begin to lose its original significance as well.

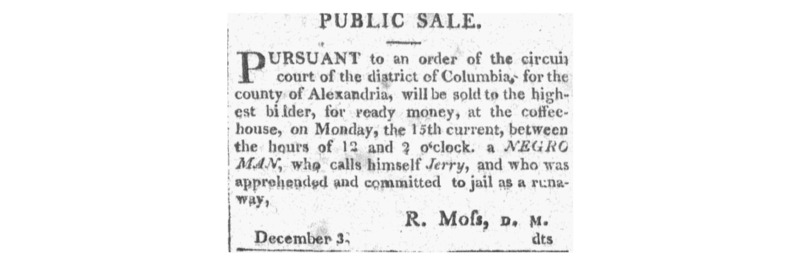

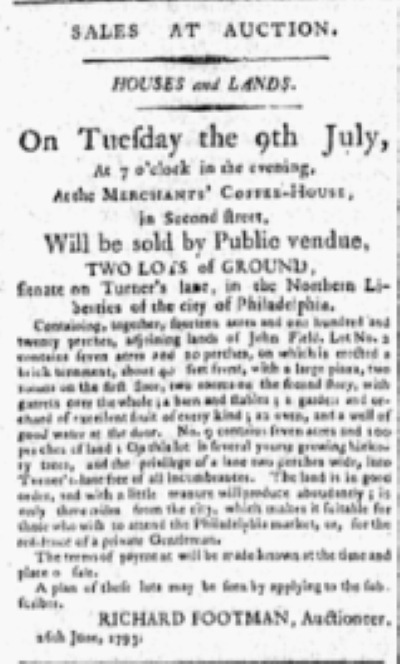

Unlike the emerging hotel industry, coffeehouses were not focused on providing room service and other comforts for lodgers. Yet, there had to be some luxuries to lure the upper class. Hannah’s Alexandria “Coffee-House” on Royal Street boasted what is believed to be the largest room in the entire town the year it was built, 1785. Referred to as the assembly room, it can still be viewed on the second floor of the museum that is located on the premises today. The multiple windows allowed light and air flow, and two fireplaces kept the space comfortable in the winter cold weather. The assembly room had been used previously to host balls, other entertainment, and even the occasional teeth-pulling by a traveling dentist. Coffeehouses made use of such spaces for auctions of merchandise, land, and sometimes enslaved people.

In addition to auctions, these areas were used to hold large meetings of the town’s merchants or club assemblies for members only. Paying a regular subscription fee for membership to a coffeehouse ensured that only men of means would enter and thus guests would, in theory, be free from association with the less civilized sort. Sometimes referred to as “penny universities,” proprietors and patrons perpetuated the idea that coffeehouses were “cultural centers” for intellectual discussion and sophisticated games such as chess.

Many clubs comprised of wealthy men who shared a certain passion such as poetry or even a particular food, like hominy, met regularly in coffeehouse rooms and often with much invented ceremony.[4] To attract and maintain such clientele, it was imperative that a coffeehouse operator possess “respectability.” Privilege allowed Hannah to avoid the poorhouse and make use of her advantageous name and connections to open a coffeehouse that prioritized providing a sophisticated environment for affluent and influential merchants.

Hannah may have lived on the premises with her children, this detail is currently unknown, but it would not have been uncommon for a proprietor to do so. She was fortunate enough to operate her business as the nation’s economy continued to improve greatly and while wiping a table or straightening cups, Hannah may have overheard any number of topics being discussed. Recently celebrated revolutionary ideals of that era had sparked a short, but remarkable, period of contemplation and debate on issues such as women’s rights and the morality of slavery. Coffeehouses served not only as a private place in a public space for businessmen to network and discuss these topics as well as more confidential matters, but they also provided access to the latest information regarding arrival and departure of ships, current prices of goods, and even reports of weather and other events that would affect those prices. Besides this, coffeehouses advertised auctions of land and other expensive items; selling bulk goods like barrels of flour and even tickets for passenger ships. There were even auctions of enslaved individuals. As the system of chattel slavery was the source of America's economic assent onto the world stage, Hannah's coffeehouse and others like it would have profited greatly, directly and indirectly, from the slave trade. Such an atmosphere attracted wealthy enslavers, slave traders, and professional "slave catchers" who met with clients and negotiated deals. Even someone seemingly opposed to slavery, such as a Quaker insurance man, profited from the institution by way of insuring ships used for transporting goods and enslaved laborers.

[1] “Fairfax Deed Book Index, 1742-1866,” Books A-Z. Fairfax County Historic Records Center Deed Books, https://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/circuit/historic-records-center/finding-aids/deeds

[2] Paton Yoder, “Tavern Regulation in Virginia: Rationale and Reality,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 87, no. 3 (July 1979), 260, 264.

3 David S. Shields, Civil tongues and polite letters in British America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1997), 199.

[4] David S. Shields, Civil tongues and polite letters in British America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1997), 57, 61- 62, 199.

Created by Kristy Huettner, 2020.