The Beginning of the American Traveler

His first great adventure occurred during the American Revolution, but his fame would not be on a battlefield, rather as a British marine sailing the world under a British ensign. While in his writing after the voyage he would refer to himself and the other members of the expedition originally from the colonies as “American,” what that meant at the time was in flux. Ledyard and his American brethren may have been called American, but were probably understood to be colonist, as they would not learn of the Declaration of Independence until 1778 and would return to England before the issue was decided.

Ledyard returned to America in October of 1781, having succeeded in avoiding service as British marine in the American theater. He determined his best future lay as an American, his ambitions for a commission as a British officer having been rebuffed, and deserted to Long Island where his mother ran a boarding house. His reintegration into his family and community was helped by his lacking association with either the patriot or loyalist cause and his service with the British being on an acclaimed voyage.[1]

In Among the Powers of the Earth: The American Revolution and the Making of a New World Empire, Eliga Gould argues that American survival required recognition as a treaty worthy nation to the powers of Europe and making defensible claims on the North American continent still unsettled by Europeans. By extension, establishing the who and what of the United States also depended on commerce, including the need for recognition by and rights to trade with, China and colonial powers in the Far East.

American identity was also established by the interactions between Americans and the cultures they were encountering on a global scale. Dane Morrison uses print culture to explore the issue of identity and what he framed as national self-confidence in his True Yankees: The South Seas and The Discovery of American Identity. The importance of being recognized as a nation was also crucial in dealing with commercial and transportation issues in other parts of the world – Morrison tells of the supercargo on a China trader not being afforded the same courtesies of passage on vessels as the European nations offered each other, stranding him in Macao.[2]

Identifying the Americans separately in his narrative of his travel with Captain James Cook may have been a choice based on his citizenship in a new nation, especially since he lost several family members in Benedict Arnold’s raid on Groton and New Haven. Publishing immediately following what was a civil war, war for independence and a global conflict, clearly identifying with the United States was critical to the success he aspired to in the new nation.

Later, before his departure for Russia, he would offer his cousin Isaac Ledyard as an explanation for his venture:

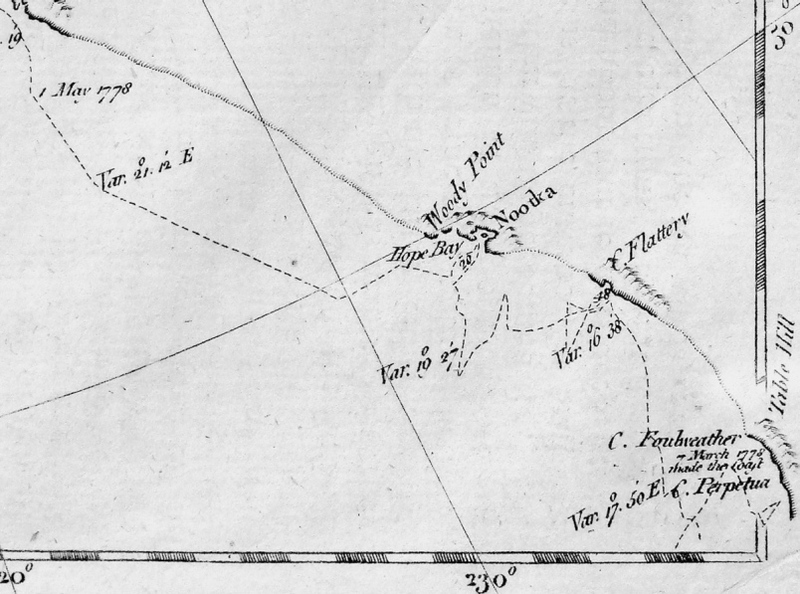

“A blush of generous regret sits on my Cheek to her of any discovery there (Northwest Pacific Coast) that I have not part in, & particularly at this auspicious period…a Native only could feel the pleasure of the Atchievement. It was necessary that an European should discover the Existance of the Continent, but in the name of Amor Patria, Let a Native of it Explore its Boundary. It is my wish to be the Man.”[3]

[1] Gray, pp. 3-4.

[2] Dane A. Morrison, True Yankees: The South Seas and The Discovery of American Identity (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014), p. 37.

[3] John Ledyard to Isaac Ledyard, August 8, 1786 in Stephen D. Watrous, editor. John Ledyard’s Journey Through Russia and Siberia, 1787-1788: The Journal and Selected Letters. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2011) ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.mutex.gmu.edu/lib/gmu/detail.action?docID=3445171, pp.106-17