The Press

“...for the Good of the Community I now publish the Proceedings, to deter the Licentious, and Dregs of the Earth, as well as others, from acting as Ruffians.” -Cornelius Calvert[1]

Any narrative reconstruction of the Norfolk Riots relies heavily on two colonial newspapers: the Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon) and the Virginia Gazette (Rind). These outlets were considered the only consistent, reputable sources of information available to Virginians[2]. This brings a few facts into focus.

First, the publishers of each newspaper influenced the very ideas their audience could consider. These men received think-pieces and testimonies through submissions, and could curate their content accordingly.[3] How the Norfolk Riots were reported is how they are remembered. Modern audiences have no choice but to take the publications of the Virginia Gazettes as truth. For this reason the truth of events is perhaps less important than how the publishers framed it or who they lended their platform to.

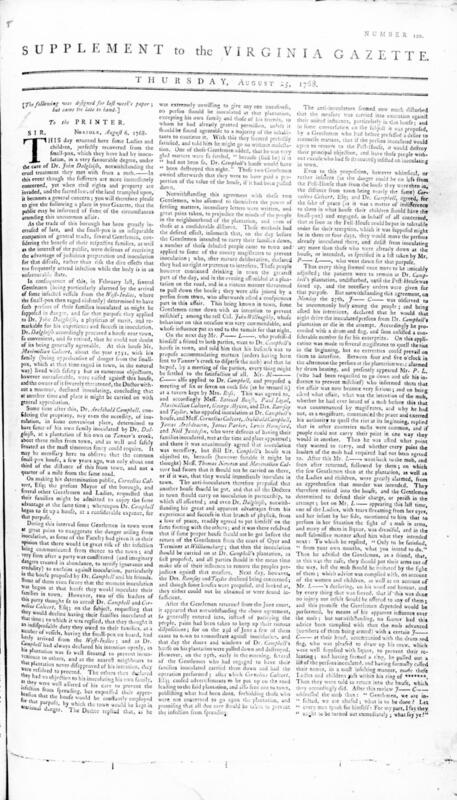

One should also note that both newspapers ran an anonymous account of the Norfolk Riots in August of 1768. This publication greatly sympathized with the pro-inoculators.[4] Subsequent issues included essays responding to this account. Authors, anonymous and not, were desperate to clear themselves of its accusations or elaborate on its details. This is curious, considering the politics of Norfolk and the gazette publishers.

Publishers Purdie, Dixon, and Rind initially claimed a “neutral” or “balanced” position in their gazettes that gradually evolved into staunch Patriot rhetoric.[5] By the Revolutionary War there was no doubt both Virginia Gazettes supported American independence. Yet these publishers chose to curate sympathy for pro-inoculators who were largely Loyalists. One has to wonder why they would give this group a voice at all. The answer may lie with America’s Founding Fathers.

Understand that the people penning narratives for the Virginia Gazettes were well educated. The initial August account of the Norfolk Riots utilizes vivacious and classical allusions that suggest the author was one of the victimized pro-inoculation Gentlemen.[6] The published response that followed sarcastically used allusions of its own, indicating the author defending the named anti-inoculation Gentlemen belonged to that same group.[7] These (assumed) Gentlemen may be adversaries in Norfolk, but they belonged to the same land-owning, Enlightened class as the Founding Fathers. More specifically, Founding Fathers who advocated for inoculation. The struggles of the pro-inoculators highlighted and ultimately contributed to an intellectual movement that many of the Founding Fathers championed: the widespread acceptance of inoculation.

It’s apparent that the Virginia Gazettes were meant to appeal to literate, Patriot Enlightenment thinkers who would enthusiastically embrace modern medicine. It is unsurprising, then, that the publishers Purdie and Dixon ran a copy of Voltaire’s defense of inoculation the same month they reported on the Norfolk Riots.[8] Likewise, Rind ran an advertisement for inoculation the very same month the Norfolk Riots happened.[9] The pro-inoculation Gentlemen may have been Loyalists, but their struggles contributed to an ongoing conversation about inoculation that both Virginia Gazettes were determined to facilitate.

At this point, one has to consider how the Founding Fathers factor into conversation surrounding inoculation, and how they tie back to Norfolk. Thomas Jefferson actually represented several pro-inoculators in the trials that followed the Norfolk Riots.[10] Jefferson was a stalwart defender of inoculation who chose to be inoculated himself.[11] His presence inevitably pulled the riots into a larger context. It became a chain in a string of attempts by the Founding Fathers to shape America’s public health and intellect.

Benjamin Franklin shared Jefferson’s enthusiasm for inoculation sixteen years before the Norfolk Riots ever took place. In a letter to his acquaintance, John Perkins, he reported on inoculation’s remarkable successes in Philadelphia. Over a period of twenty-two years, only four of eight hundred patients died as a result of the procedure.[12] This meant seven hundred and ninety-six people had gained an immunity to one of America’s most antagonistic diseases. Even more would benefit from the treatment in the Revolutionary War.

George Washington vigorously advocated for inoculation.[13] He had survived smallpox the “natural” way, and became convinced inoculation was one of the best protections against it.[14] Washington went so far as to inoculate the entire Continental Army 1777.[15] This proved to be a brilliant decision as it spared his soldiers from a wave of smallpox that rampaged through Continental and British armies alike. Washington, Franklin, and Jefferson popularized inoculation, and their actions helped overturn laws implemented after the Norfolk Riots that restricted inoculation in Virginia.[16]

In a strange twist the Virginia Gazettes empowered the Patriot movement by granting the pro-inoculators of Norfolk the public’s sympathy. By publishing accounts of pro-inoculators being brutalized by an ignorant mob and harassed by local officials (namely Joseph Calvert), the newspapers encouraged readers to see inoculation as progressive science unduly rejected. Its champions, the Founding Fathers, then become figures of admiration. Just as they put forward modern ideas for governance, they advocated for superior, modern ideas about medicine. With this interpretation, it makes sense that the publishers of the Virginia Gazettes were willing to lend Loyalists their platform.

Footnotes

[1] Cornelius Calvert, The Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon, VA), Jan. 09, 1772.

[2] Willard Frank. “Rousing a Nation: The ‘Virginia Gazettes’ and the Growing Crisis 1773-1774 1773-1774 .” Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects (1962): 8.

[3] Frank, “Rousing a Nation,” 8.

[4] Patrick Henderson, "Smallpox and Patriotism: The Norfolk Riots, 1768-1769." The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 73, no. 4 (1965): 416.

[5] Frank, “Rousing a Nation,” 10.

[6] The Virginia Gazette Supplement (Rind, VA), Aug. 25, 1768.

[7] The Virginia Gazette Postscript (Purdie and Dixon, VA), Sept. 8, 1768.

[8] Voltaire, The Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon, VA), Aug. 11, 1768.

[9] John Smith, The Virginia Gazette (Rind, VA), June 09, 1768.

[10] Frank Dewey, "Thomas Jefferson's Law Practice: The Norfolk Anti-Inoculation Riots." The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 91, no. 1 (1983): 39.

[11] Dewey, "Thomas Jefferson's Law Practice,” 39.

[12] Benjamin Franklin to John Perkins, August 13, 1752.

[13] Fritz Hirschfeld, Smallpox, the Continental Army, and General Washington (William & Mary, 1991), 22.

[14] Hirschfeld, Smallpox, the Continental Army, and General Washington, 24.

[15] Hirschfeld, Smallpox, the Continental Army, and General Washington, v.

[16] Hirschfeld, Smallpox, the Continental Army, and General Washington, 24.