Her Husband Becomes a Legend

David Griffith trained in Philadelphia and London, first acquiring a medical degree and later a Doctorate of Divinity. Members of his denomination, the Church of England, also referred to as Episcopalians, were worried about the influence of other sects, such as Quakerism and Methodism, as Anglican congregations declined in numbers. David was one of the concerned Episcopalians who sank deeper into the study of Anglican Church doctrines until the young husband and physician decided to embark upon an ecclesiastical career which would take he and his young bride far from New York.

Law required proof of ordainment by the bishop of a diocese in England in order for a minister to receive appointment to a parish. A parish was the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the Anglican Church, and a glebe was the land belonging to the Church on which ministers often lived and farmed. Typically, there were two or three churches in a parish, and the minister would be responsible for splitting his time and attention between them, preaching sermons on alternate Sundays and facilitating baptisms, weddings, funerals, and the usual sacraments, in addition to overseeing the farming of glebe lands.[1] Glebe sizes often exceeded the Virginia required minimum of two hundred acres, but the land had to be farmed in order to produce any profit for the minister, his parish and the Church. This meant that Hannah very likely oversaw the labor of many enslaved men and women who the parish, or her husband directly, “hired” (paying their enslavers) to cultivate, harvest, and dry the tobacco that provided income for her family’s needs.[2]

Finding himself in charge of the Shelburne Parish of Loudon County, Virginia when the American Revolutionary War erupted, David enlisted and served a dual commission as surgeon and chaplain in the Continental Army. Dr. Rev. Griffith would soon become a legendary figure of the War when, according to accounts repeated by Washington Parke Custis, Griffith advised General George Washington of potentially dangerous behavior on the part of Major Charles Lee, which Griffith felt could lead to a perilous situation the next day on the Monmouth battlefield. Turned away by guards at first, Griffith insisted on speaking with Washington and his warning is often credited for Washington's early intervention the next day which avoided disastrous consequences when Lee began to retreat unexpectedly.

Besides being known for Monmouth, Cornwallis would permit Griffith to cross enemy lines unharmed to tend to prisoners of war. In addition, at Washington's command, Griffith would return home to Loudon County briefly during the winter at Valley Forge in order to administer smallpox inoculations to the reluctant public in an effort to stop the spread of the disease which had been devastating Continental soldiers and civilians alike. Griffith’s work in Loudon may have been the first action of “public health” in the county.[3]

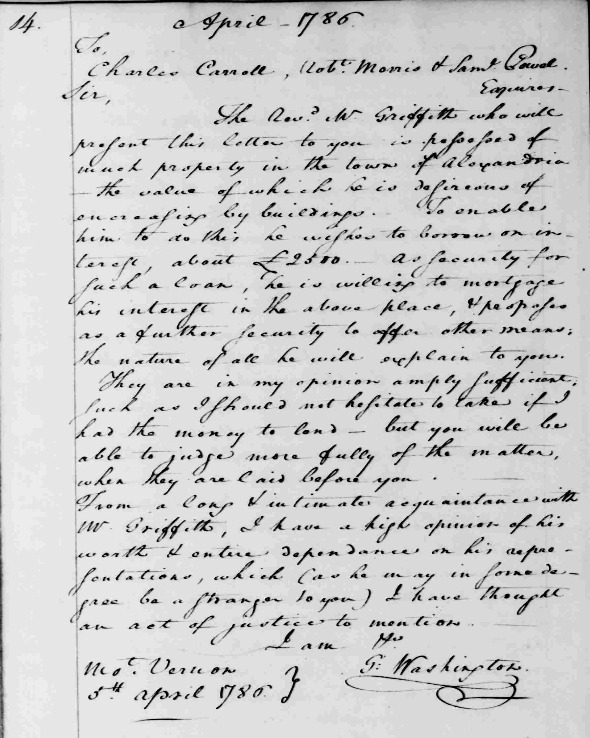

David finished his military career at last and in March of 1779 he moved Hannah and the family straight to their new home to begin work as rector for the two churches comprising Fairfax parish.[4] The 516-acre glebe and brick house provided for the Griffith family sat halfway between the two churches of the parish—the Alexandria Church, now known as Christ Church, and the Falls Church.[5] David had known of the “genteel” vestrymen of that parish, George Washington among them, when he agreed to accept the job. Though a salary was never really agreed upon, it was obvious to him that the congregation he would now be serving could afford to support their minister and his family.[6] Hannah may have been wary of this, seeing how the conflict with Britain had ceased trade and injured the economy. But soon her mind would be focused on the coming of their fourth child, a son born on February 25, 1780.

She named him Colvill, a derivative (without the “e”) of her father’s surname. She would remain in the Glebe House and accompany her husband, wrangling their brood of capricious offspring, to Sunday sacrament and community events when she was able. However, she had a great deal to do in her own household and, besides the four little ones—the oldest being ten in 1780—she would give birth to four more children within the next nine years.

During those eventful years, Hannah stood witness not only to her personal dramas, but to the end of the War with the 1783 Treaty of Peace. But, instead of peace and prosperity, the new nation plunged into a crippling economic depression with many wealthy landowners drowned by debt as currency depreciated at a startling rate. She may have been especially sensitive to these worry as the couple struggled more and more to support their growing family. There was little William, who was named for her father, and Alfred, Camillus, and sweet Sarah who carried the name of David’s beloved mother (whom records show was still alive many years after the move to Fairfax, but there is no evidence as to where she resided after leaving Shelburne). Throughout their time in Fairfax, Hannah watched her husband leave several times to visit with his parishioner and military comrade, George Washington. He often stayed overnight at Mount Vernon, due to the distance.

Washington’s diary provides a wealth of details regarding the social and business-related visits from Reverend Griffith—such as, the selling of geese and transfer of saplings for planting at Mount Vernon. They spent hours of conversation over dinner, and breakfast following the overnight stays. Though it is apparent from Washington’s documentation, that wives and even children did accompany their husbands for dinner, and even overnight visits to Mount Vernon, Hannah is never mentioned in Washington’s detailed journals, as having joined her husband on these outings. We also do not know if she was present at other momentous occasions, such as the funeral her husband conducted for Ann McCarty Ramsay.

[1] Rev. Philip Slaughter, The History of Truro Parish in Virginia, (Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs & Company, 1907), 100.

[2] Jennifer Oast, Institutional Slavery: Slaveholding Churches, Schools, Colleges and Businesses in Virginia, 1680-1860 (Cambridge: Cambridge U

[3] Rev. Philip Slaughter, The History of Truro Parish in Virginia, (Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs & Company, 1907), 100.

[4] David Griffith, letter, David Griffith to Hannah Griffith, Nov. 6, 1777. Griffith papers, manuscript collections, Virginia Historical Society.

Created by Kristy Huettner, 2020.