The Mob

“...in other countries mobs were common, and if people could not carry their point in one way they would in another.” - Paul Loyal [1]

Traditional Virginian society often reinforced communal will.[2] Then came the imperial crisis, which divided Norfolk’s Gentlemen and further distanced them from the public.[3] The interests of Norfolk’s political and economic elite, particularly those that lauded inoculation, were consequently misaligned with the concerns and feelings of the general public. The Norfolk Riots can then be explained as the natural result of everyday people trying to reassert communal authority over people who refuse to hear them.

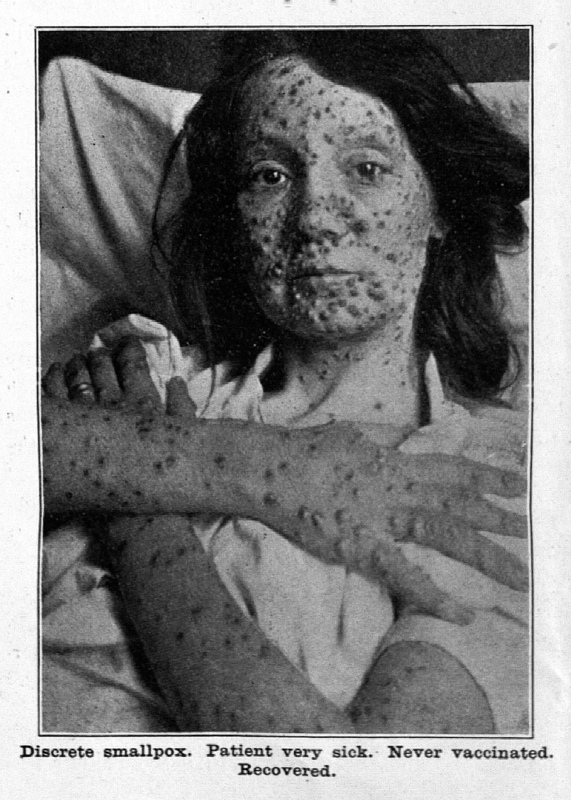

Evidence suggests the leaders of Norfolk’s pro- and anti-inoculation factions had ulterior conflicts during the riots that did not stem from inoculation itself. These same sources highlight the terror of the mob. Published accounts of the Norfolk Riots, whether they mocked or defended the mob, acknowledged the general public was terrified the inoculated families of Norfolk would infect the rest of the town. This fear was exacerbated by the town’s previous smallpox outbreak (1751-52) and the pro-inoculation Gentlemen’s apparent disregard for public safety.

Norfolk was ravaged by smallpox in 1751.[4] The disease continued to kill and maim townsfolk throughout the year, and only slowed in 1752. This understandably traumatized the survivors mentally, physically, and financially. If Samuel Boush is to be believed, Norfolk’s parish spent upwards of 800 pounds on charitable services during this outbreak.[5] Yet many of Norfolk’s families were still ruined. This trauma explains the town’s general apprehension towards inoculation in 1778.

“We presume there is no necessity for explaining to the publick why the inhabitants opposed inoculation with so much warmth: The number to be inoculated, at the Doctor’s price, would cost more money than is circulating in Norfolk; the doctors and nurses would only be benefited…” -Anonymous [6]

Inoculation’s primary purpose was to safely grant patients immunity to smallpox. This required doctors to handle organic samples from mildly ill patients, and to care for their inoculated patients until they were wholly healthy. It is not unreasonable to assume that a careless or mercenary doctor might botch the procedure and infect others as a result. A community’s willingness to accept inoculation comes down to its trust in the doctors performing the procedure, then. Unfortunately the common people of Norfolk did not trust Dr. Dalgleish or Dr. Campbell.

Dr. Dalgleish had earned his community’s ire a year prior to inoculating the families of Cornelius Calvert, Archibald Campbell, James Archdeacon, James Parker, Lewis Hansford, and Neil Jamieson. He did so by inoculating his apprentice, Mr. Robert Bell, in June of 1767.[7] Dalgleish defended his choice, claiming it was a precautionary measure meant to preserve Bell’s life and prevent him from spreading the disease.[8] Doctors and their apprentices regularly interact with highly contagious, diseased people after all.

Once the procedure was completed, Dr. Dalgleish sent his apprentice to the Pest House and publicly announced what he’d done. Town residents were furious. Some accused Dr. Dalgleish of scheming. They believed Dalgleish was trying to popularize inoculation so that he might extort Norfolk’s residents with doctor’s fees.[9] So riled was the town that legal charges were very nearly brought against Dr. Dalgleish. Fortunately, Paul Loyal is rumored to have prevented those charges from sticking.[10] While Dalgleish denied all claims, residents remained wary. His association with Campbell did nothing to assuage their doubts.

Dr. Campbell was far less popular than Dr. Dalgleish. This is likely due to the fact that he was Scottish and a devoted Loyalist[11] in a town with growing nativist sentiments. As such, he was on the receiving end of several vicious rumors. The most notable implied he was exceptionally greedy and eager to bleed the town dry with inoculation procedures.[12]

Anti-inoculation Gentlemen asserted themselves as defenders of the poor, and in doing so they marked Dr. Campbell as a danger to the public. They claimed the doctor wanted the inoculation to take place on his plantation in Tanner’s Creek. His choice to do must have been motivated to not lose business by sending patients to another county.[13] If he went through with the inoculation, however, everyone in town would also have to be inoculated to prevent infection. This would bankrupt Norfolk, as Campbell supposedly charged an exorbitant amount for the inoculation procedure.[14] Meanwhile, the poor and working class would be wholly unable to pay for the procedure.[15] Assuming smallpox did spread through the community, this would be a death sentence for them.

The assumptions above may seem dubious, and perhaps they are. The entire town was never inoculated. No one outside of the inoculated was even reported sick. These presumptions did prey on existing fears, though. Dr. Dalgleish inoculating someone without the approval of his community gave credence to rumors that he was arrogant or money-hungry. He did not appear to value the opinions of his neighbors. Similarly, Dr. Campbell’s foreignness makes him an outsider; he was easy to “other” and ascribe negative values to. If local Gentlemen claimed this inoculation procedure was unsafe, and if they were supported by local doctors Ramsay and Taylor, it’s no great mystery why the frustrated townspeople devolved into a mob.

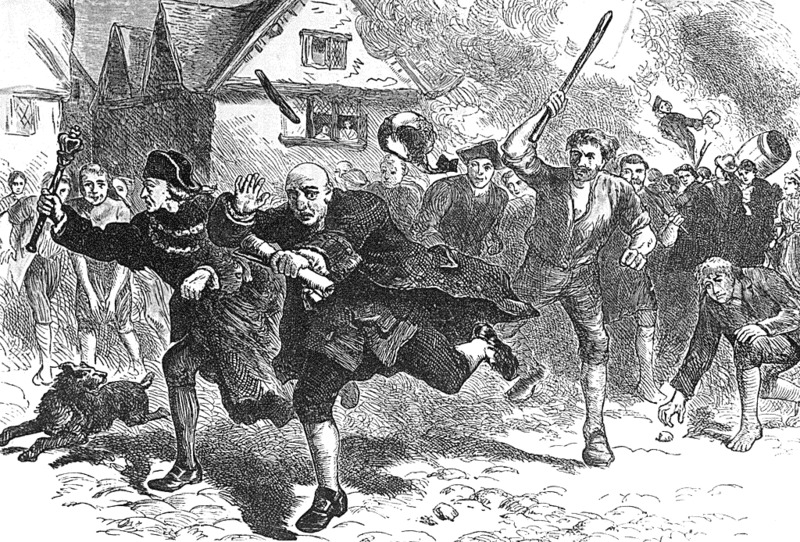

One anonymous witness to the Norfolk Riots, presumably a pro-inoculation Gentlemen, portrayed the mob as irrational and wild. The inoculated were forced from Dr. Campbell’s plantation to the Pest House on the basis that it would be safer for the town,[16] and the author rightly pointed out the flaws in this logic. The Pest House and plantation were roughly the same distance from town. Moving the inoculated to the new location wouldn’t protect Norfolk’s residents from smallpox any more effectively than if they had stayed, isolated, in Dr. Campbell’s home. What the author fails to consider is that the riots were about more than safety. They were about control.

The pro-inoculation Gentlemen repeatedly dismissed the community’s concerns about inoculation while anti-inoculators validated them. Each time anti-inoculatrs approached them, the pro-inoculators insisted the procedure was safe and that they were going through with it. Right or not, this behavior would make any group feel unheard. By forcing the inoculated off the plantation and into the Pest House, the mob reasserted the joint authority of Norfolk’s inhabitants. Practically this did not make the townsfolk any safer, but it granted them a peace of mind. The feeling of having done something is sometimes more rewarding than the actual task. It gives one a sense of autonomy. When considering the mob, modern audiences should take into account humanity’s innate desire for control over their life and their wellbeing. It is the same desire that, in part, inspired the Revolutionary War.

Footnotes

[1] The Virginia Gazette Supplement (Rind, VA), Aug. 25, 1768.

[2] Kristan Crawford, ‘“Exciting the Rabble to Riots and Mobbing’: Community, Public Rituals, and Popular Disturbances in Eighteenth-Century Virginia,” Dissertations, Theses, and Master Projects (2015): 30.

[3] Crawford, “Exciting the Rabble to Riots and Mobbing,” 62.

[4] Crawford, “Exciting the Rabble to Riots and Mobbing,” 64.

[5] Samuel Boush, The Virginia Gazette (Rind, VA), Aug. 29, 1768.

[6] Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon, VA), Sept. 8, 1768.

[7] John Dalgleish, The Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon, VA), Oct. 20, 1768.

[8] John Dalgleish, The Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon, VA), Oct. 20, 1768.

[9] John Dalgleish, The Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon, VA), Oct. 20, 1768.

[10] John Dalgleish, The Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon, VA), Oct. 20, 1768.

[11] Patrick Henderson, "Smallpox and Patriotism: The Norfolk Riots, 1768-1769." The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 73, no. 4 (1965): 414.

[12] The Virginia Gazette Postscript (Purdie and Dixon, VA), Sept. 8, 1768.

[13] The Virginia Gazette Postscript (Purdie and Dixon, VA), Sept. 8, 1768.

[14] The Virginia Gazette Postscript (Purdie and Dixon, VA), Sept. 8, 1768.

[15] The Virginia Gazette Postscript (Purdie and Dixon, VA), Sept. 8, 1768.

[16] The Virginia Gazette Supplement (Rind, VA), Aug. 25, 1768.