Promoting Education

Promoting Education

Focusing on moral and domestic education, rather than solely religious education, became more prevelant at the end of the eighteenth century. Women's education evovled in one sense through Dr. Benjamin Rush, who argued that women should be educated not only in the basic skills, but also in the principles of liberty and government. He believed these skills were necessary to teach future generations, as “the first impressions upon the minds of children are generally derived from women.”[1] Therefore, they needed be educated to teach and embody the morals of the new United States.By gifting books and industrial items, the giver encouraged this exact thing. Both young men and young women received these types of goods, especially by the mid-nineteenth century. It helped enhance their intellectual abilites to participate and facilitate important conversations.[2]

A domestic or industrial education encouraged young women to be actively engaged in society.

[1] Benjamin Rush, Essays, Literary, Moral, and Philosophical (Philadelphia, 1798), 6-7.

[2] See: Lindsay O’Neill, “Networking in the Epistolary World,” in The Opened Letter: Networking in the Early Modern British World (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), specifically 108-112, for information on women and networking in the eighteenth century.

Literary gifts

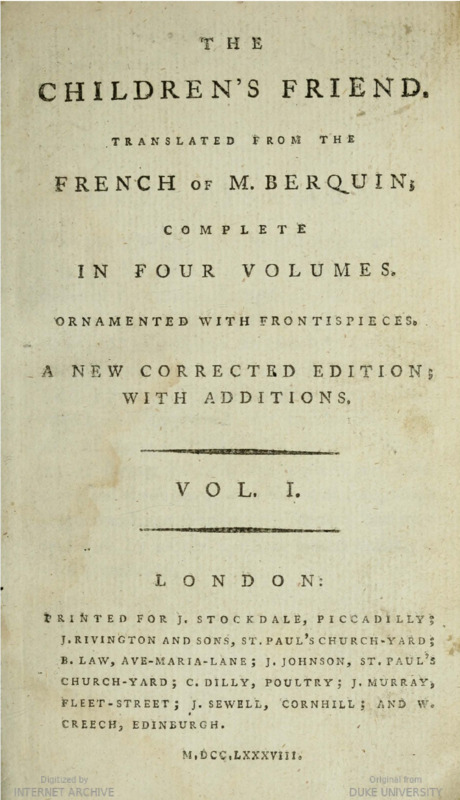

The Children's Friends

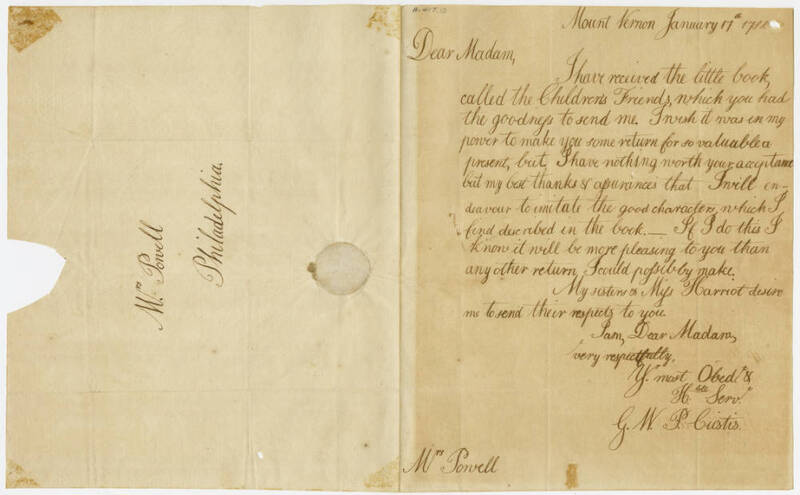

Recipient: George Washington Parke Custis (1781-1857)

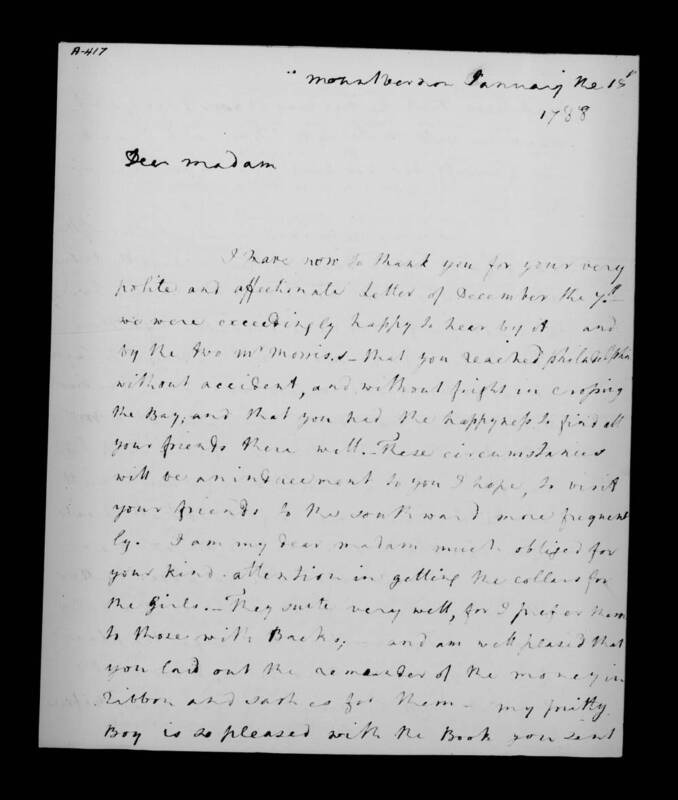

Elizabeth gifts this book to George Washington Parke Custis, the grandson of George and Martha Washington, after the Powels visited Mount Vernon in 1787. This book has little stories with lessons about morals and education. She gifted this book to GWPC for just that. He understands the point, as shown in his thank you note to Elizabeth, when he says:

"I have received the little book, called The Children’s Friends, which you have the goodness to send to me. I wish it was in my power to make you some return for so valuable a present, but I have nothing worth your acceptance but my best thanks & assurances that I will endeavor to imitate the good characters which I find described in the book."

See more correspondence related to this gift in the item showcase below.

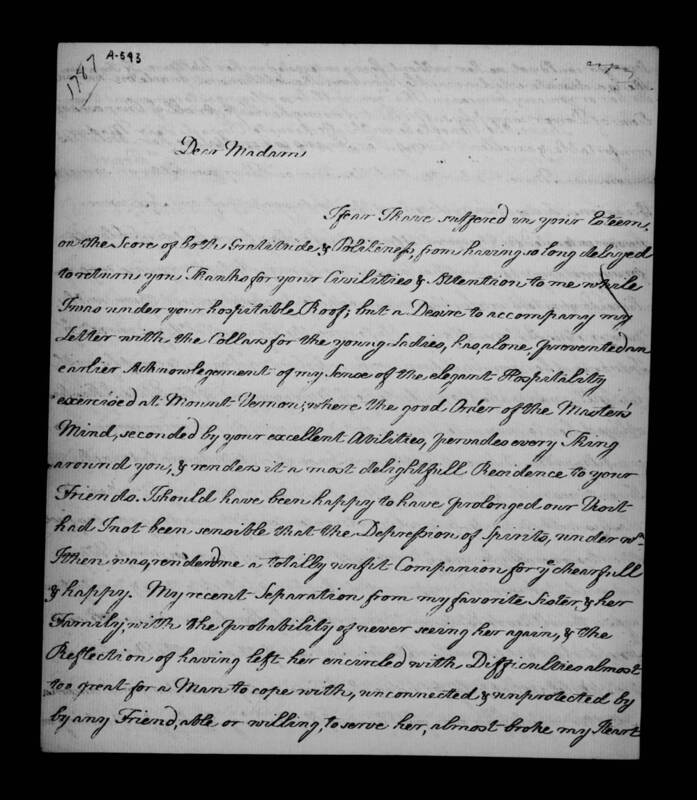

Martha Washington to Elizabeth Willing Powel, 18 January 1788

Martha Washington to Elizabeth Willing Powel, 18 January 1788

Elizabeth Willing Powel to George Washington Parke Custis, 10 May 1788

Elizabeth Willing Powel to George Washington Parke Custis, 10 May 1788

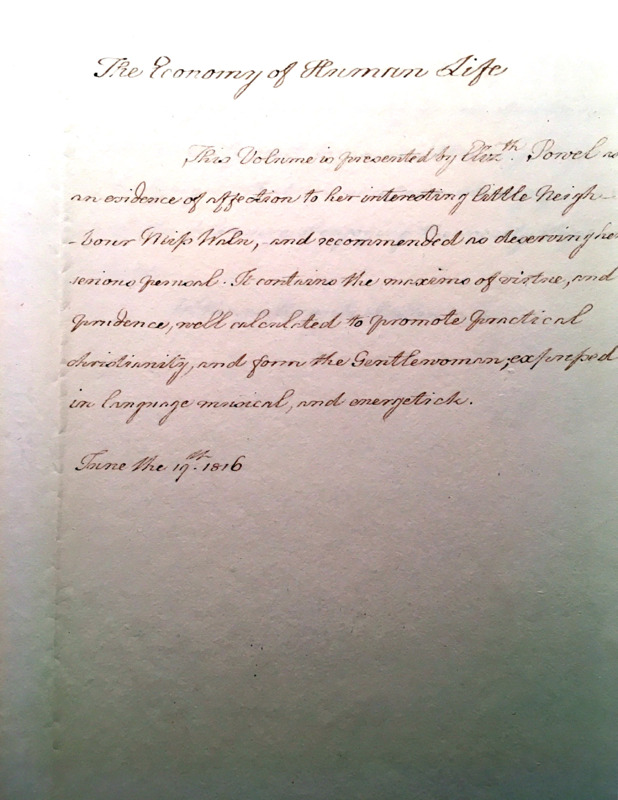

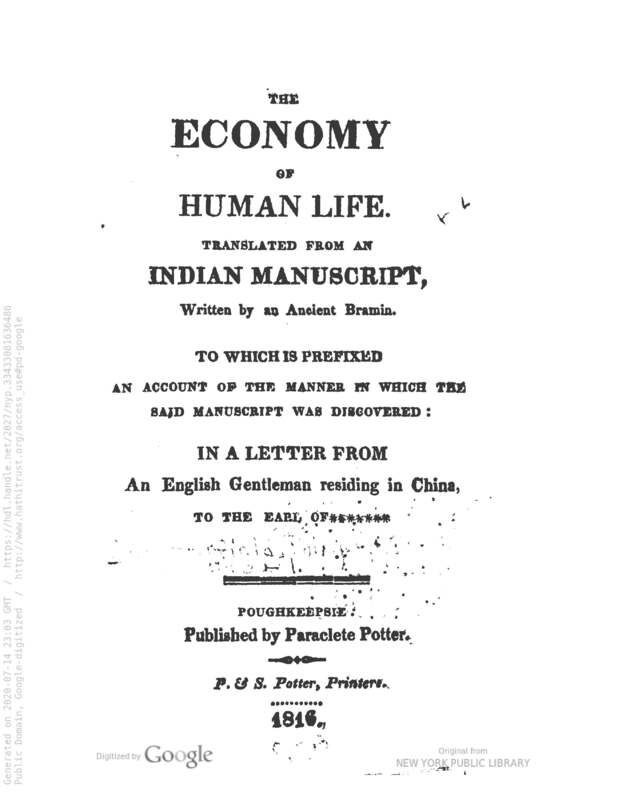

The Oeconomy of Human Life

Recipient: Sarah Waln (1806-1886)

Elizabeth Powel gifted this book, to her "interesting little neighbor," Sarah Waln, in 1816. Sarah Waln was the child of the Waln family, an important family in Philadelphia who lived next door to Elizabeth Powel from the early 19th century until 1830.

The book was first published in 1751, is a collection of essays "moral precepts" of ancient writers. It was best seller throughout the eighteenth century, and Elizabeth previously recommended it to her nieces in 1783. With its popularity, Elizabeth may have read it herself as a young woman.

Industrial and domestic gifts

Thimbles

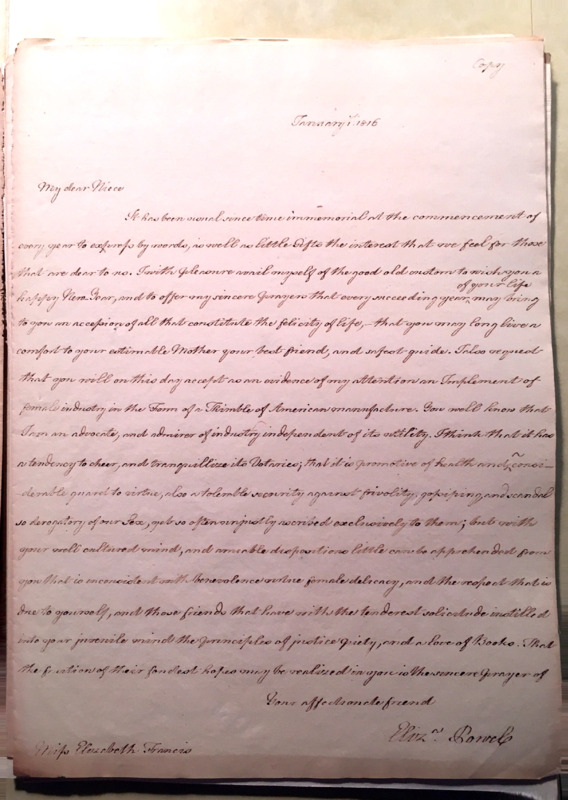

Recipients: Elizabeth Francis (1796-1866) and Elizabeth Haslett (unsure of age)

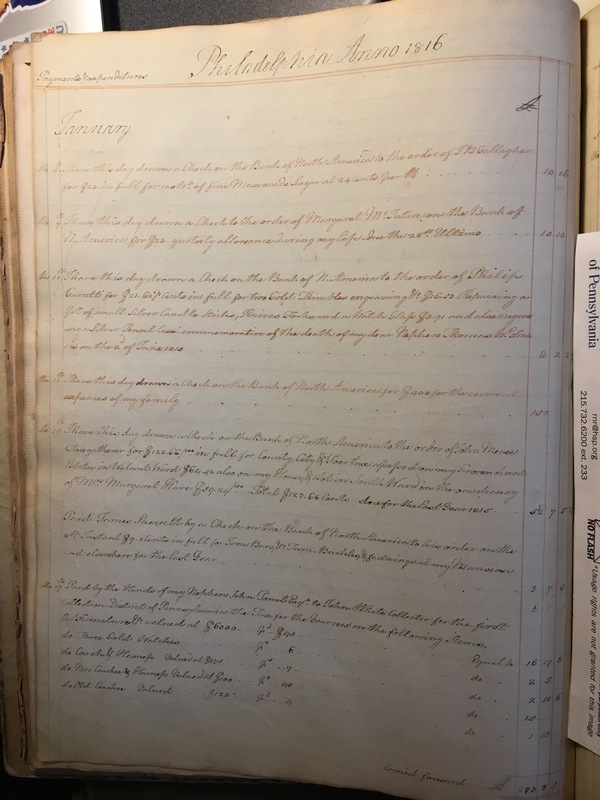

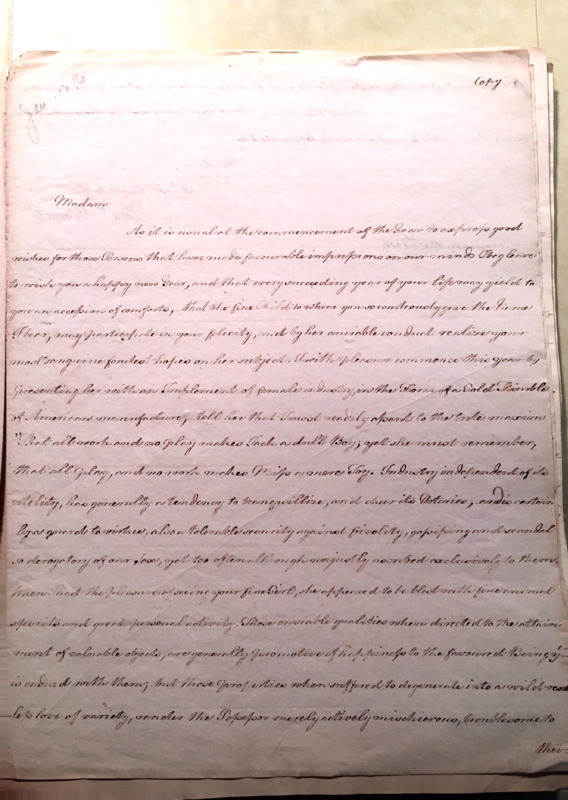

Elizabeth gave thimbles to multiple young women in her family and extended connections. Two examples are her niece Elizabeth Francis and tha family friend (whom Elizabeth refers to as her "namesake") in 1816. Thimbles were one of the most common gifts for young girls, and Elizabeth purchases multiple thimbles throughout the nineteenth century. These specific gifts were given for New Years gifts, a popular trend of the period. This gave the impression for the young women to start the year off with productivity. Elizabeth had both of these pieces engraved, and though it is unclear if she included her own name, it again establishes legacy throughout multiple generations, showing that Elizabeth helped encourage young women in their industrial pursuits.

In her letter to Elizabeth Haslett's mother, Elizabeth describes her reasoning for the gift:

"...Tell her that I must readily assent to the trite maxim “that all work and no play makes Jack a dull Boy”; yet she must remember, that “all play, and no work makes Miss a mere Toy.” Industry independent of its utility, has generally a tendency to tranquillize, and cheer its Votaries; - and is certainly a guard to virtue, also a tolerable security against frivolity, gossiping, and scandal so derogatory of our Sex, yet too often although unjustly ascribed exclusively to them."

See more about the purchase of these thimbles in the item showcase below.