Walker's Call for Black Unity

“There is great work for you to do... You have to prove to the Americans and the world that we are men, and not brutes, as we have been represented, and by millions treated.”

David Walker, Walker’s Appeal in Four Articles

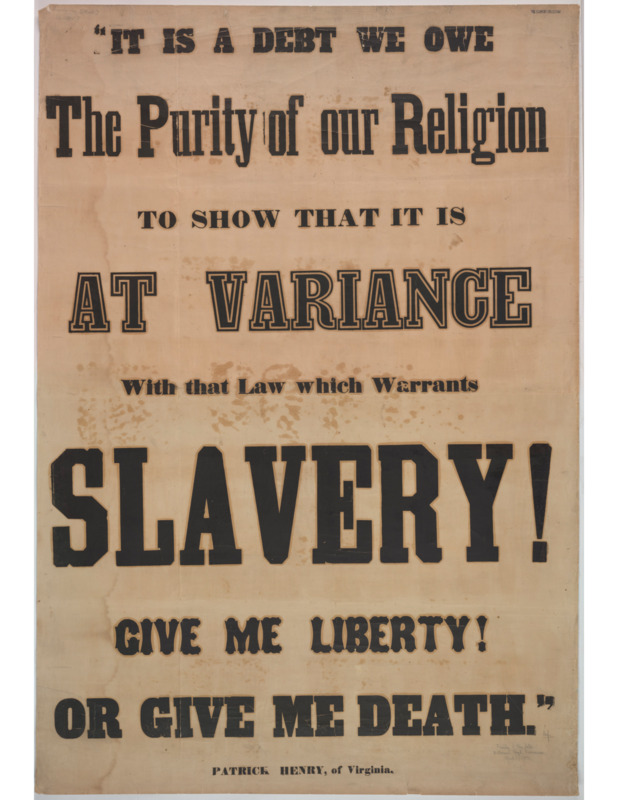

In the face of radical antislavery rhetoric from black activists like David Walker, white southern landowners initiated a new defense of slavery as a virtuous, wholesome system for both whites and allegedly subordinate and inferior blacks. Historian Bruce Dain tells us that Walker’s repudiation of attempts to whitewash slavery’s brutality in his Appeal recognized the devastation caused by, from among all slave societies of the past, the particular cruelty of American slaveholders’ failure to acknowledge enslaved blacks’ humanity.[1] Walker’s Appeal clarified the free black community’s obligation to alleviate their enslaved brethren’s burden, and in doing so, tapped into and exploited white fear of slavery’s capacity to create social upheaval, such as uprisings among the enslaved, and negative outcomes associated with a mass influx of freed blacks into the general population.

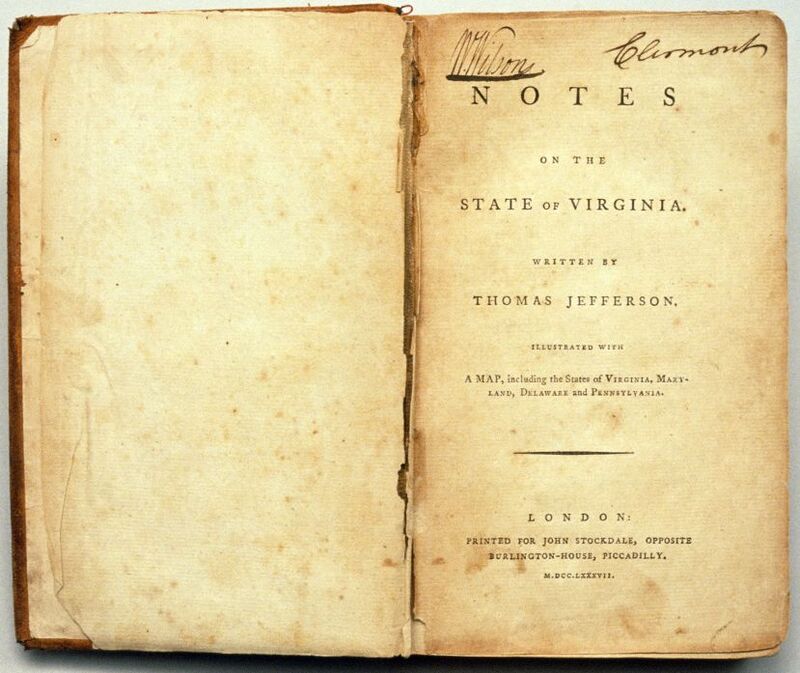

Walker devoted ample space in the Appeal to critique and counter Thomas Jefferson’s assertions in Notes on the State of Virginia regarding the inherent, biological subservience of blacks, citing and responding to Jefferson repeatedly in the first two articles of his Appeal.[2] Jefferson believed blacks, by the laws of nature, to be incapable of participating in the American republic as full citizens, writing, “I advanced it, therefore, as a suspicion only, that the blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time or circumstances, are inferior to whites in the endowments of both body and mind.”[3] Walker sought not only to repudiate Jefferson and other whites’ unfair justifications for black oppression based on scientific theories regarding their natural inferiority, but also to use the Founding Father’s own enlightenment and liberty rhetoric to argue that slavery itself contributed to the blacks’ lack of social, political, and intellectual progress, writing,

“Has Mr. Jefferson declared to the world, that we are inferior to the whites, both in the endowments of our bodies and of minds? It is indeed surprising, that a man of such great learning, combined with such excellent natural parts, should speak so of a set of men in chains. I do not know what to compare it to, unless, like putting one wild deer in an iron cage, where it will be secured, and hold another by the side of the same, then let it go, and expect the one in the cage to run as fast as the one at liberty.”[4]

In direct contradiction of Jefferson’s beliefs, Walker’s Appeal repudiated the racism and hypocrisy of white Americans, and sought to affirm the African American community’s political agency to work against slavery’s abuses and inequities. Walker's pamphlet clarified the responsibility of all blacks to overcome their oppression, and uniformly demand, by any means necessary, an immediate end to slavery in the United States.

[1] Bruce Dain, A Hideous Monster of the Mind: American Race Theory in the Early Republic, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003), p. 142

[2] Gene Andrew Jarrett, “’To Refute Mr. Jefferson’s Arguments Respecting Us’: Thomas Jefferson, David Walker, and the Politics of Early African American Literature,” Early American Literature 46, no. 2 (2011), p. 297

[3] “Africans in America/Part 3/Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia,” PBS (Public Broadcasting Service), accessed July 11, 2021, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part3/3h490t.html.

[4] Walker, Appeal, p. 16.