Charles C. Jewett's vision for the Smithsonian Institution

Charles C. Jewett was well educated but did not come from a family of means, which led to his affinity for libraries from an early age. While attending Brown University, he and a friend organized a collection of library books, and later at seminary in Andover, he helped a professor catalogue their library’s books alphabetically according to the author’s last name, but also cross-referenced by subject, the system he used when he published the Catalogue of the Brown University Library in 1843. These early experiences influenced his passion, and practical interest in cataloguing library books. He graduated from Brown University, where he was eventually hired as the first full time, paid, professional Librarian. By the time Congress passed the act for the Smithsonian in 1846, Jewett had gained a national reputation as a librarian, especially regarding his work with cataloguing books.

Within Congress, there were debates over whether a national library should be funded by the Smithsonian Institution, or left to the Library of Congress. One of the biggest proponents for a public library was Senator Rufus Choate of Massachusetts who argued that many more would stand to benefit if it was freely accessible to all, and not just to the legislators. In fact, some members of the Board of Regents thought a national library was so important that a Librarian was the only other position besides that of Secretary whom they selected. But when offered the position in 1846, Jewett was hesitant to accept. When he and Joseph Henry met for the first time in December of 1846, it was clear that, while they both agreed that an ‘increase’ of knowledge was more important than ‘diffusion’ of knowledge, they disagreed over the role that a library should take within the Smithsonian Institution, an ideology that would continue to hamper their professional relationship during Jewett’s time at the Smithsonian. He accepted the position as the first Librarian of the Smithsonian in early 1847, with a goal to “overcome all opposition to his dream of a great national library,” knowing the challenges he would face. So he agreed to a compromise that the library would be a ‘bibliographic centre’ instead of a collection of books, for the time being. But he still had his own personal interests, and plans he hoped to accomplish. To Jewett, public libraries were not only about increasing knowledge, but they also had a higher purpose related to class and democracy, where the wealthy could afford books, while those of lesser means would need the help of the government, and a means to break a monopoly of access to higher education by the wealthy. Ultimately, Congress included provisions to include some money for a library, which Henry begrudgingly accepted, believing that more money should fund scientific research with the purpose of a library for support.

In his first annual report to the Board of Regents in 1848, Jewett explained his intent, for the purpose of placing “American students on a footing with those of the most favored country of Europe, is the design of the Smithsonian Library (Harris, 86). ”He planned to purchase books, including complete collections of the most important around the world, to make the Smithsonian Institution a center of bibliographical reference, and to accept donations of private collections to a national library (Harris, 90). The remaining funds of this department would be devoted to the purchase of books of general importance; at first, most especially those which are not to be found in other libraries of the country. (Harris, 86). In conclusion, he stated that he believed a great library, “to rank among the largest, the best selected, and the most available literary treasurer-houses of the world (Harris 86).” He believed that Washington DC, as the political center of the nation, would be the most favorable location, “spread in ever-widening circles over the land, softening the asperities of party contentions, calming the strifes of self interest, elevating the intellect above the passions and the senses, cherishing all the higher and nobler principles of our being, and thus contributing more than fleets and armies to true national dignity (Harris, 87-88).”

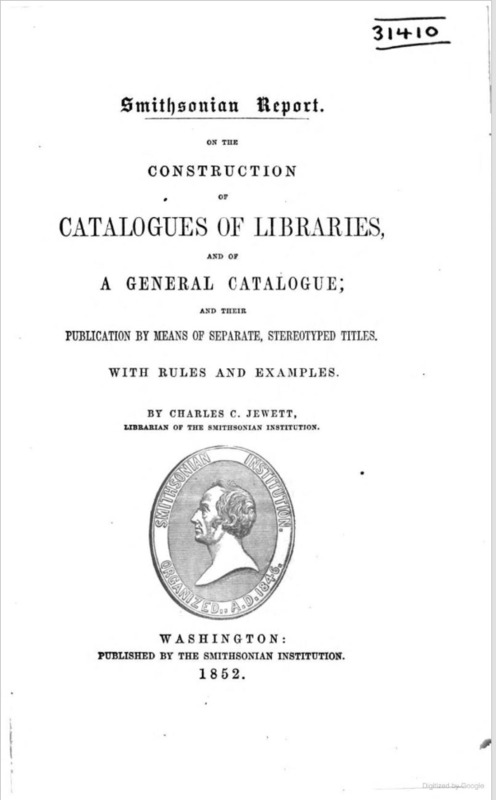

Writing to Secretary Henry in 1850, Jewett discussed the importance of creating a general catalogue of all the books in all the public libraries in the US, believing that no one has attempted such an endeavor on such a large scale as of yet. In addition to creating a universal catalogue, Jewett also suggested to ‘stereotype’ the catalogue, for the purposes of eliminating repeated, duplicate printing. Stereotype in print had been used for newspapers, whereby for words that would be used frequently there were models, made of either paper-mache or clay, that could be stored, instead of setting the same words anew for each printing. Stereotyping had not been used for library cataloging, but Jewett believed it could revolutionize the organization of lists of available books world-wide, saving time and money. He also sought contact with all existing public libraries in the US for the purpose of conducting a survey of their collections of books, which was eventually compiled into his Notices of Public Libraries in the United States of America, 1851. Unfortunately for Jewett, the stereotyping did not work, which he considered a great failure. However, his universal cataloging of books and standard rules of procedure were one of his greatest accomplishments during his time as the first librarian of the Smithsonian. They were explained in detail in his most important published work, On the Construction of Catalogues of Libraries, which emphasized the necessity of uniformity, and alphabetizing bibliographic information of books. His ideas were influential in the creation of union catalogues of public libraries in the US, the precursor to electronic databases used worldwide today.