France

"... for my eye now caught distinctly for the first time the objects on that shore which I had so long wished to see; and I stood as if transfixed by an enchanter's wand."

Willard's trip to France was focused on discovering the similarities of education between America and Europe. She focuses on the morality of education, the educational structures, as well as understanding how the French and American cultures lead to differences between education practices. In her writings, this is where she includes multiple letters to her students. Her time in France reflects an idea of American Exceptionalism, in that she documents how she believes no country's educational practices, or culture are as strong as America's own.

A visit with the Marquis de Lafayette

Every stop Willard made in France had a specific reason behind it. This portion of her trip was focused on moral lessons for her students, understanding french culture, visiting with her friend the Marquis de Lafayette, and visiting French schools. While in France, she documents the often tumoltuous goings-on around her. The most specific event she writes about is the Revolution in 1830. She was not in France during the event, but was fascinated with the affair, and lauded her friend the Marquis de Lafayette's role in it as the acclaimed "Leader of the Revolution." He flatters her with his belief that... "he looked upon the government of the United States as by far superior to any other existing."1

Willard's close relationship with the Marquis de Lafayette is a specific example of the still close ties between America and France. Lafayette met Willard on his own American tour six years prior, and they maintaned a friendship of mutual support across the Atlantic. Her time with Lafayette in at his home, La Grange, in France gave her access into other networks of individuals within Paris and the surrounding areas. Out of all her stops in Paris and the surrounding areas, this visit is clearly one she took for mostly personal enjoyment, rather than for the benefit of her students.

1. Emma Willard, Journal and Letters from France and Great Britain (Troy: N. Tuttle, 1833), 41.

Stroll in the Gardens of the Tuileries

One feature of Paris in the early nineteenth century that was a popular destination were the numerous gardens in the city. One such garden, the Garden of the Tuileries (pictured here) was a pleasure garden meant for viewing of numerous sculptures purchased by royals over the years. This example is one of Willard's lessons to her "pupils" or her "girls" about the sculptures themselves. It shows how she's adapting her time abroad for future curriculum builidng, but keeping the students one step removed. This reflects the broader idea of women's education in the eighteenth century, how it was so focused on enhancing women's morals. This section, written as though she's talking directly to the students as though they are with her. She only does these short pieces three times during her time in France, as though she's undertsood that this time is more of a "foreign" experience rather than England, which many of the girls may think of as home.

She writes, "wait, say you, what about the gay garden below us, where we are going to join that cheerful throng, and examine those beautiful statues. No-- my dear girls. I shall not take you to examine those statues. If your mothers were here, I would leave you sitting on these shaded benches and conduct them through the walks and they would return and bid you depart for our own America; where the eye of modesty is not publicly affronted; and where vergin delicacy can walk abroad without a blush."1

1. Emma Willard, Journal and Letters from France and Great Britain (Troy: N. Tuttle, 1833), 63.

"Perfectly educated women"

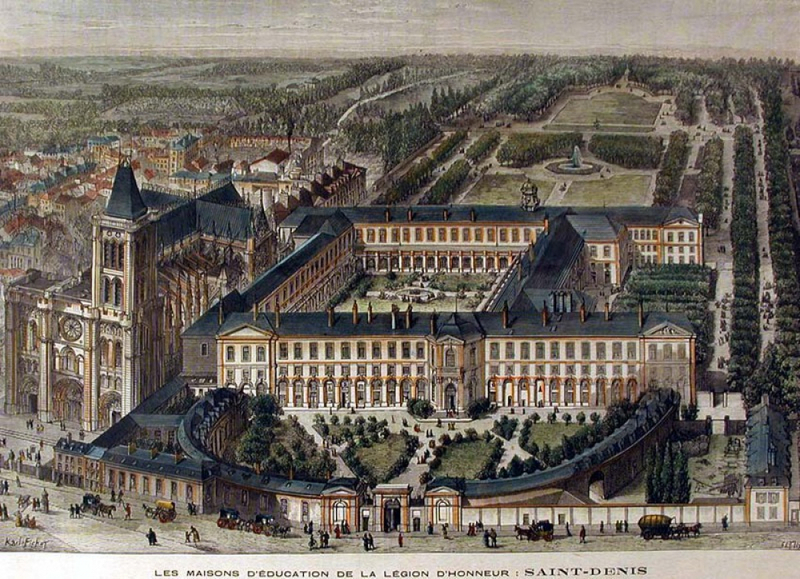

Willard acknowledge that her "first object is to learn the state of education in France, particularly that of my own sex, yet no species of information seems so difficult of attainment." She was vastly unimpressed with what she did find, and would soon visit the schools of London in hopes of more similarities with America. Prior to her departure for London, Willard visited the Maisons d'Education de la Legion d'Honneur: Saint Denis, a french school started by Napolean for the daughters of French soldiers. Willard was connected with the head of this school through a mutual connection in Paris, and documented her trip in a letter to her sister. She is doesn't believe that the ornamental education these women learn is enough, though the french believe they are "parfaitement instruite, (perfectly educated)."1

She goes on to describe their curriculum:

"...she can speak a certain number of languages, play on so many instruments, and perhaps to this list it is added that she understands mythology and history, and is mistress of drawing. This is evidence to me not only of the defective, but of the wrong views here entertained of female education. Yet if the female mind could become the subject of a proper moral and intellectual culture, how would the evils which abound in Paris be ameliorated! How different had been the past history of France, if the influence of women had been what it should be!"2

This difference helps her believe that her work in America is so important, for she believes she is doing far more than these women are for their students in France. Willard focuses on making women useful members of society, rather than pretty ornaments to entertain others.

1. Emma Willard, Journal and Letters from France and Great Britain (Troy: N. Tuttle, 1833), 93.

2. Emma Willard, Journal and Letters from France and Great Britain (Troy: N. Tuttle, 1833), 94.