Issues & Dissemination of Campaign Rhetoric

In the era before the 1800 Presidential election, if there was any major consensus between the Federalist and Republican political parties, it was that events in Europe would ultimately be influential in the New World, and in particular, matters involving France and the French Revolution.[1] [2] The relationship between France and the U.S. in this period generates myriad problems that will eventually become election issues in the 1800 campaign: XYZ Affair, the undeclared naval war with France (“Quasi War”), and the passage of the Alien and Seditions Acts (four acts curtailing civil liberties, most importantly “freedom of the press”). Other issues included religious freedom and established churches, immigration, and the size of the public debt.[3]

Modern campaign rhetoric can be delivered in many different ways not imaginable in the Early American Republic (e.g. on-line social media). This in no way diminishes the ability of the candidates and their supporters from effectively delivering their messages in the 1800 election, except that the volume and speed at which it was disseminated was smaller and slower. Among the methods deployed were public meetings, speeches and correspondence of the candidates, their surrogates and other actors supporting them, along with newspapers (including paid advertisements), pamphlets, handbills and other campaign materials, and informal methods (e.g. political gossip) describing the issues and respective positions of the candidates and their advocates.

One of the more interesting and influential methods of dissemination of campaign rhetoric, not usually thought about systemically, was political gossip.[4] In her book, Affairs of Honor, Joanne Freeman devotes an entire chapter to what she calls the “Art of Gossip”. In her view, one of the most skilled practitioners of this art was Thomas Jefferson, who undertook to make a record of his conversations for posterity (his so-called “Anas”).[5] She describes political gossip to be “private discussions of revealing, immoral, or dangerous behavior learned and passed on through unofficial channels'; an ordinary event and an important means of practicing politics. Hamilton is quoted in Freeman’s book; calling gossip to be “malicious intrigues to stab me in the dark”.[6] In his text, Anas, Jefferson recites personal anecdotes over and over again about consistent themes: Monarchist, money-man, corrupter, and schemer, and almost always attached to a Federalist.[7]

A common form of distribution for campaign rhetoric in the Early American Republic was the use of pamphlets, inexpensive paper-backed booklets. In his 95-page pamphlet published in 1799, Jame Callender, a notorious Jefferson supporter, lays out some of the issues in the election of 1800.[8] Admittedly antagonistic to President Adams and the Federalists; a infamous quote from this pamphlet referring to Adams follows: “a hideous hermaphroditical character, which has neither the force and firmness of a man, nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman." Callender goes on to further lists the following campaign issues: corruptions and misconduct of the Adam’s administration, Quasi-War crisis, antipathy towards France and the French Revolution and the Federalist refusal to permit voters to choose presidential electors in many states in the 1796 election. In spite of the prohibitions of Alien and Sedition Acts (another important campaign issue), Callender concludes that the 1800 election presented a clear choice of outcomes: “Adams and war, or Jefferson and peace”.[9]

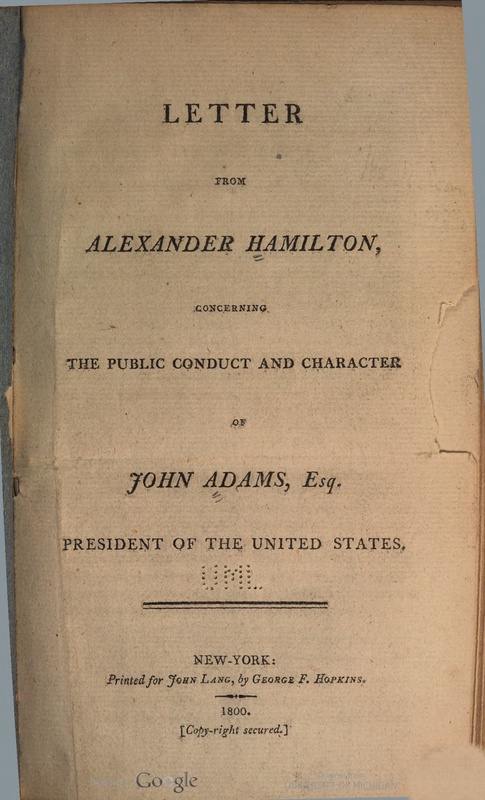

Another interesting example of campaign rhetoric is 54-page pamphlet published in October 1800 by Alexander Hamilton stating his issues with John Adams standing for President again, despite both being prominent leaders of the same political party. His litany of defects in the character of Adams run the gauntlet of anger, weakness, egotism, vacillation, eccentric tendencies, bitter animosity against his cabinet and policy issues. Interestingly, Hamilton makes no charges of corruption or misconduct; he even praises Adam’s patriotism and integrity, and concedes that Adams has “talents of a certain kind”. In the end, Hamilton even concludes that Adams must be supported equally with Pinckney in the election.[10] Here’s a representative extract from this pamphlet:

“In executing this task, with particular reference to myself, I ought to premise, that the ground upon which I stand, is different from that of most of those who are confounded with me as in pursuit of the same plan. While our object is common, our motives are variously dissimilar. A part, well affected to Mr. Adams, have no other wish than to take a double chance against Mr. Jefferson. Another part, feeling a diminution of confidence in him, still hopes that the general tenor of his conduct will be essentially right. Few go as far in their objections as I do. Not denying to Mr. Adams patriotism and integrity, and even talents of a certain kind, I should be deficient in candor, were I to conceal the conviction, that he does not possess the talents adapted to the Administration of Government, and that there are great and intrinsic defects in his character, which unfits him for the office of Chief Magistrate.”

This document is certainly not helpful to Adam’s campaign, but emblematic of a larger issue. While Hamilton is from the same political party as Adams, he is also is the leader of a major dissident faction of the Federalist Party, often referred to as “High Federalists”. This faction represents a signification opposition to Adams continuing in office and some historians believe that it contributes to Adam’s losing the election in 1800.[11]

[1] Elkins, et al, The Age of Federalism: The Early American Republic, 1788-1800, Page 303 ff

[2] Larson, Magnificent Catastrophe: The Tumultuous Election of 1800, America’s first Presidential Campaign, page 67

[3] Ferling, Adams vs. Jefferson : The Tumultuous Election Of 1800, Page 148

[4] Freeman, Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic, Page 62 ff

[5] Freeman, Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic, Page 65

[6] Freeman, Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic, Page 68

[7] Freeman, Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic, Page 74

[8] Ferling, Adams vs. Jefferson : The Tumultuous Election Of 1800, Page 136

[9] McCullough, John Adams, Page 537

[10] McCullough, John Adams, Page 545-550

[11] Ferling, A Leap in the Dark: The Struggle to Create the American Republic, Page 456-457