Key Points of Walker's Appeal

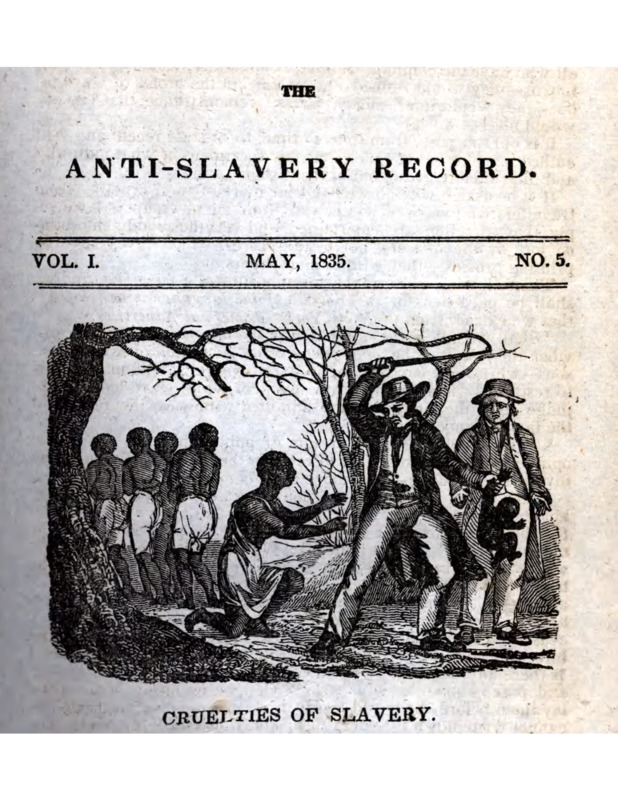

In the 1820s, David Walker migrated to Boston from North Carolina to run a used clothing store. As a free black man, Walker’s exposure to southern slavery had created in him a powerful antagonism to its brutalities, and he soon became an influential figure in Boston’s black abolitionist community. Historians mark David Walker’s significance to the early abolitionist movement mainly through the lens of three of his ideas:

- His powerful call for black unity in advocating for slavery’s ending and rights for African Americans.

- His condemnation of racist proslavery tactics such as colonization and miscegenation.

- His forceful insistence that blacks be prepared to achieve emancipation from slavery through violence, if necessary.

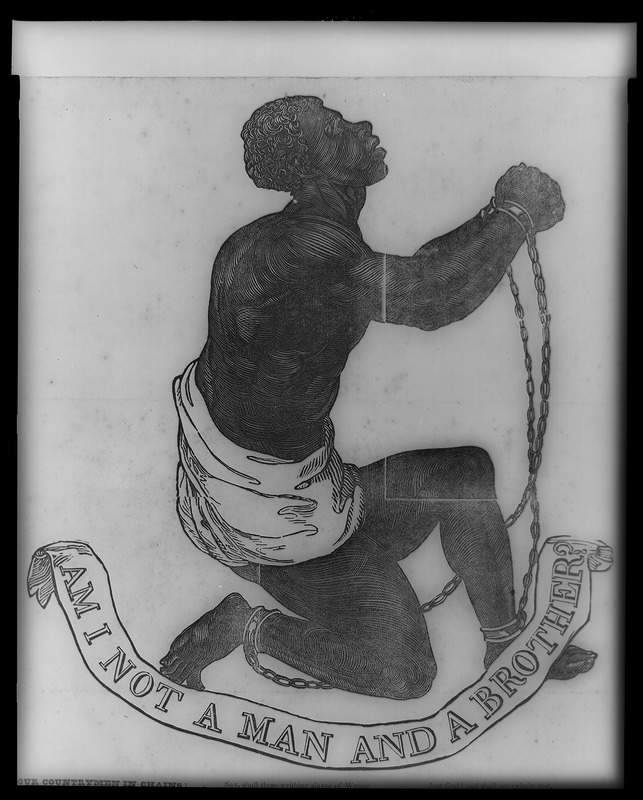

Walker’s use of “appeal” in his pamphlet’s terminology imbued blacks with political status and embodied the sensibility and rationality of self-determining African Americans.[1] Accordingly, Walker’s Appeal, a potent seventy-six-page antislavery pamphlet, affirmed both the evils of slavery and the necessity for blacks to elevate themselves.

[1] Melvin L. Rogers, “David Walker and the Political Power of the Appeal,” Political Theory 43, no. 2 (December 2014): p. 227

Walker’s Appeal represented the most courageous and pioneering plan for empowering African American resistance that Americans had ever seen.[1] Walker’s tone of outrage in the controversial tract exemplified a growing willingness among Northern black reformers to publicly decry slavery’s incongruence in a republic dedicated to inalienable natural rights. In the Appeal’s preamble, Walker vividly described the impact of slavery’s cruel injustices, writing,

“HAVING travelled over a considerable portion of these United States, and having, in the course of my travels, taken the most accurate observations of things as they exist—the result of my observations has warranted the full and unshaken conviction, that we, (coloured people of these United States,) are the most degraded, wretched, and abject set of beings that ever lived since the world began; and I pray God that none like us ever may live again until time shall be no more.”[2]

Walker’s resolve to share his ideas as widely as possible, especially in the South, put his life at risk, and demonstrated his determination to inspire and motivate both free and enslaved blacks to cohesive self-awareness in regard to their capacity for defiance against slavery, their fundamental equality with whites, and their collective power over oppression.

[1] Peter P. Hinks, To Awaken My Afflicted Brethren: David Walker and the Problem of Antebellum Slave Resistance, (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997), p. xv.

[2] David Walker, 1785-1830. Walker's Appeal, in Four Articles: Together with a Preamble, to the Coloured Citizens of the World, but in Particular, and Very Expressly, to Those of the United States of America. Written in Boston, State of Massachusetts, September 28,1829, accessed July 12, 2021, https://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/walker/walker.html. p. 3