Moral Suasion and Redemption

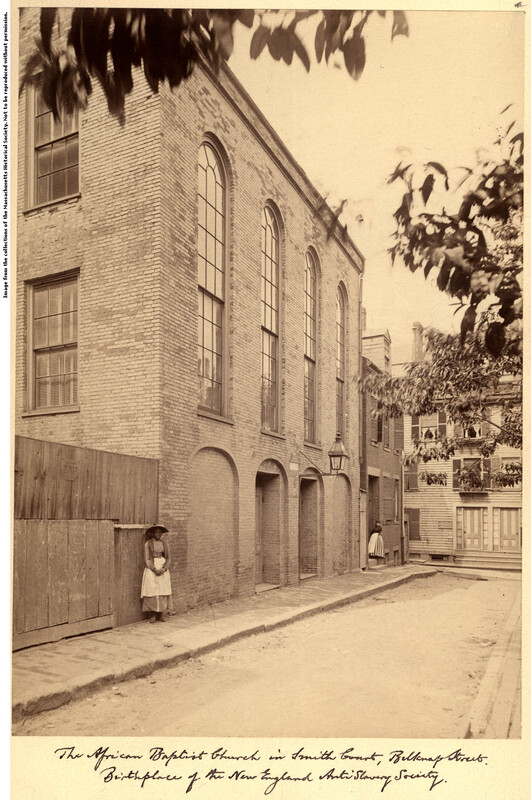

African Meeting House, Boston, Massachusetts

The African Baptist Church in Smith Court, Belknap Street. Birthplace of the New England Anti Slavery Society

Garrison and Walker’s viewpoints notably diverged on the conceivable necessity to bring about abolition through bloodshed. Troubled by Walker’s violent and incendiary language, Garrison wrote, “knowing that vengeance belongs to God...we deprecate the spirit and tendency of this Appeal.”[1] In the decades leading up to the Civil War, Garrison remained steadfast in his pacifism, continually expressing powerful reticence toward Walker’s and others’ advocacy of violence in opposition to prejudice and slavery. Many other prominent white abolitionists, including Benjamin Lundy, Garrison’s early Quaker mentor, shared Garrison’s objection to assertions in the Appeal that righteous violence would inevitably ensue from a failure to bring slavery to an immediate end. In Lundy’s antislavery newspaper, Genius of Universal Emancipation, where Garrison served as assistant editor for a few months at the same time of the Appeal’s initial distribution in 1829, Lundy published a strongly worded condemnation of the provocative language in Walker’s pamphlet, stating, “There can be no impropriety in an expression of sentiment, on the part of the colored people, relative to their wrongs, provided it be done in a truly Christian spirit,”[2] to establish his objections to Walker’s rageful and provocative tone primarily on religious grounds.

Henry Mayer, in his 1998 book, All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery, tells us that Garrison’s more tempered response to Walker’s indignation reflected the white abolitionist’s recognition that Walker’s arguments originated from similar impetuses to his own, such as natural rights ideology and Christian doctrines of repentance and forgiveness.[3] For example, David Walker’s Appeal promised Christian redemption for both blacks and whites upon slavery’s ending, deriving its abolitionist ethos from a powerful oratory moral suasion tradition that African American historian Tunde Adeleke tells us originated with early black abolitionist community leaders and ministers in Philadelphia and New York, not with Garrison, as commonly presumed.[4] Despite David Walker’s profound criticism of white attitudes toward slavery and civil rights for blacks, his Appeal extended antislavery and other reforms through a moral suasion lens, instigated on the premise that blacks and whites together bore responsibility for relying on reason and faith in humankind’s basic goodness to improve conditions for free and enslaved blacks in the United States.

By 1832, Garrison and his followers had formally adopted moral suasion as the official objective of Garrison’s newly founded New England Anti-Slavery Society. The society’s Constitution, stating that “whoever retains his fellow-man in bondage is guilty of a grievous wrong,”[5] codified a general philosophy intended to convince the American public that slavery should be abandoned on ethical grounds. In accordance with many of the convictions found in Walker’s Appeal, the New England Slavery Society and Garrison believed that most Americans would eventually view slavery as an immoral blight on the nation, and voluntarily agree to its abolishment. As Henry Mayer noted, “Garrison paid close attention to the ambivalent emotions that swirled through The Appeal and appreciated Walker’s ‘sensible warnings’ that an uprising could be averted through white repentance.”[6] Garrison’s subsequent long abolitionist career, contained within an unrelenting renunciation of slavery, continued to build on the moral foundation established by black abolitionists such as Walker, delineating the ethical responsibility of all whites and blacks to urgently accelerate slavery’s demise and to hasten the inclusion of blacks within the national pantheon of natural rights. Poignantly, despite Walker’s and Garrison’s shared optimism regarding the capacity of whites to overcome their racism, the bloody events of the Civil War quashed both men’s hopefulness that slavery’s redemption might be achieved quickly and by peaceful means, and instead, fulfilled Walker’s forewarning that white and black Americans must prepare themselves to purge slavery from the nation through a long, devastating, and bitter war.

[1] “Africans in America/Part 4/Editorial Regarding ‘Walker’s Appeal,’ PBS (Public Broadcasting Service), accessed July 12, 2021, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4h2929t.html.

[2] “Benjamin Lundy: Nat-Turner,” accessed July 12, 2021, https://www.natturnerproject.org/benjamin-lundy.

[3] Henry Mayer, All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery, (New York: Norton, 2008), p. 83.

[4] Tunde Adeleke, “Afro-Americans and Moral Suasion: The Debate in the 1830’s,” The Journal of Negro History 83, no. 2 (1998): p. 127.

[5] “Constitution of the New-England Anti-Slavery Society: Together with Its by-Laws, and a List of Its Officers: New-England Anti-Slavery Society: Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming,” Internet Archive (Boston: Garrison and Knapp, January 1, 1970), https://archive.org/details/constitutionofne1832newe, p. 4.

[6] Mayer, All on Fire, p. 84.