Newspaper Advocacy in Early American Republic

Equally important sources of campaign rhetoric were other print forms: newspapers, political cartoons, broadsides and handbills. Newspapers in particular were important. One reason for that, quoting Pierre Dupont de Nemours (French-American writer, economist, publisher and government official at the turn of the 19th century): while “a large part of the nation reads the Bible, all of it assiduously peruses the newspapers. The fathers read it aloud to their children while the mothers are preparing breakfast”.[1]

Both parties believed that newspaper advocacy was key to Jefferson’s election to the Presidency in 1800. Jefferson conceded that the “unquestionable effect” of the Philadelphia Aurora and other newspapers “in the revolution produced on the public mind, which arrested the rapid march of our government toward monarchy”. A Delaware Republican noted that the “great political change in the Union” was largely due to the “unremitting vigilance of Republican Printers”. Fisher Ames, a Federalist from Massachusetts, observed that “the newspapers are an overmatch for any government, the Jacobins owe their triumph to the unceasing use of this engine”.[2]

Although a majority of newspapers were supporters of the Federalist Party, newspapers supporting the Republican cause made up for their smaller number of outlets by their intensity; there were about 150 Federalist newspapers as compared to 85 Republican newspapers (mainly located in major cities).[3] Two significant Federalist newspapers, located in the capital area were the Georgetown Washington Federalist and the Alexandria Advertiser and Commercial Intelligencer. For Jefferson, his major backer was the National Intelligencer, also located in the capital.[4] Other prominent examples of Republican leaning newspapers include the afore mentioned Philadelphia’s Aurora, and the Boston’s Independent Chronicle and New York’s Argus. An interesting twist, illustrating an important campaign issue in 1800, each of these Republican newspapers became subject to multiple prosecutions under the Sedition Act or related laws by the Federalists; at least 17 indictments were issued against periodicals supporting Republican candidates with the intent of suppressing their influence in the run-up to the 1800 election.[5]

These 19th century newspapers were unlike their 21st century counterparts who try to portray a fairly objective view of current affairs. Instead, they were part of an overt adversarial political battle, designed to report and comment on political issues from the viewpoint of their sponsors, primarily partisan supporters and their respective political parties. Activities generally fell into three phases: campaigning and electioneering, crisis management, and the promotion of victory, conciliation, and party values. Postal rates for distribution of the newspapers were also highly subsidized under federal law.[6]

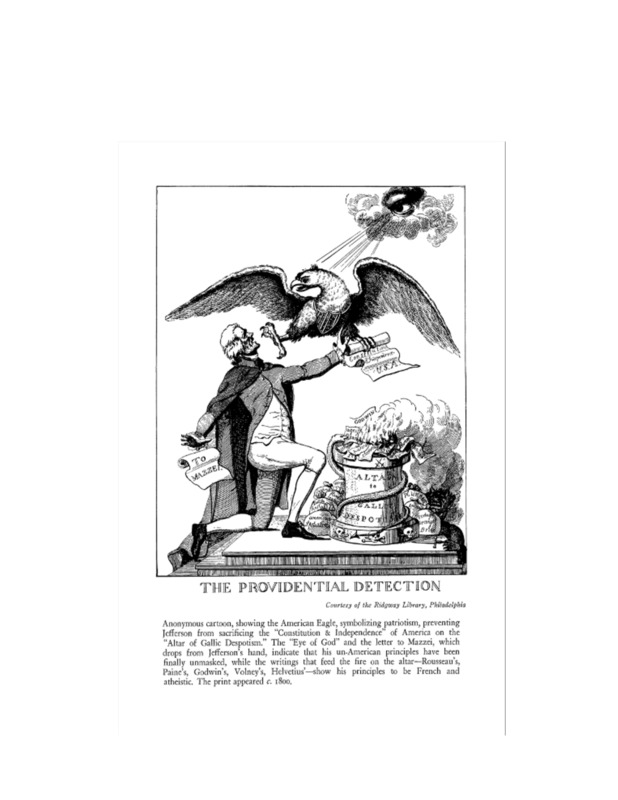

Political cartoons in these newspapers also help to shape the political discourse.

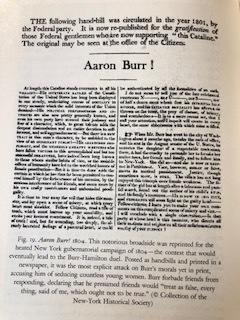

Broadsides and handbills in the era were typically large or small, single page, paper notices providing campaign rhetoric or an announcement of an upcoming political events. They could be hand-distributed or pasted onto billboards or buildings. Often displaying campaign slogans or other messaging.

[1] Laracey, “The Presidential Newspaper as an Engine of Early American Political Development: The Case of Thomas Jefferson and the Election of 1800”, Page 10

[2] Pasley, The Tyranny of Printers: Newspaper Politics in the Early American Republic, Page 105

[3] Laracey, “The Presidential Newspaper as an Engine of Early American Political Development: The Case of Thomas Jefferson and the Election of 1800”, Page 11

[4] Laracey, “The Presidential Newspaper as an Engine of Early American Political Development: The Case of Thomas Jefferson and the Election of 1800”, Page 12

[5] Larson, Magnificent Catastrophe: The Tumultuous Election of 1800, America’s first Presidential Campaign, page 74

[6] Laracey, “The Presidential Newspaper as an Engine of Early American Political Development: The Case of Thomas Jefferson and the Election of 1800”, Page 9