Peale's Methods of Display

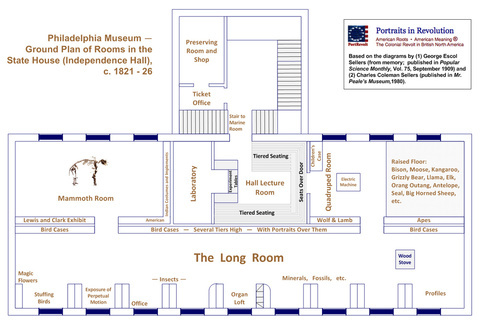

Peale envisioned his museum as “‘a world in miniature’ in which life in its variegated but ultimately harmonious forms would be on view” (Hart & Ward, 394). More specifically, collections were displayed “as links in a ‘great chain of being,’ which depicted a static universe of ascending life forms from the simplest organism to man” (Hart & Ward, 394). This sounds complicated, but for Peale, who embodied the spirit of the Enlightenment, it was anything but. The systematic layout of the museum was a testament to the harmony and order of nature. Peale closely followed the Linnaean classification method which was developed to classify plants and animals through a hierarchical structure, for his natural curiosities were to educate and provide “rational amusement” (Sellers, 27) for the general public.

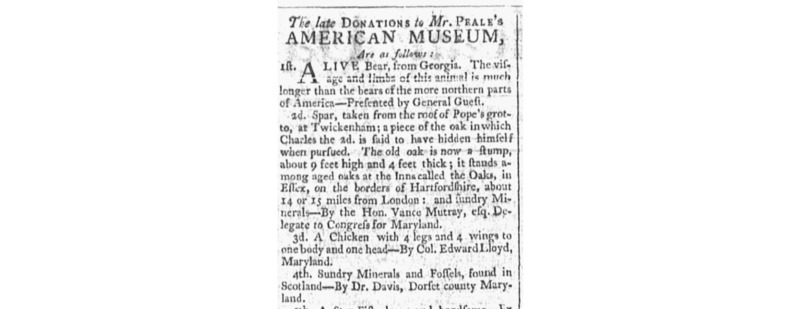

How did Peale accomplish this task of a world in miniature? Through a lot of hard work, self-taught knowledge and the donations of many fellow Americans, familiar with Peale and his quest for scientific specimens. According to Peale’s records, many of these donations arrived randomly and included: “a swordfish from New Jersey, a jackal and a mongoose from a Captain Bell, from a boy, a weasel killed in Philadelphia; twelve cases of East Indian insects, a full-grown lion (at a cost of $50), an African ostrich and Gallapagos turtle, a jaguar from St. Croix, an antelope from Senegal, a Russian sheep, insects from Canton; West Indian birds and an elephant, leopard and beaver seal from the de Peysters….”(Schofield, 30).

As was the accepted norm during this time, scientists would display specimens individually against white paper. Peale, with his artist’s attention to detail, would break this mold and display his artifacts in their natural habitat. The diorama was concept was utilized by Peale to group species together. “This ‘habitat arrangement’ describes the placing of mountings before painted backgrounds illustrating their natural environment, often with rocks, bushes and nesting materials added in the foreground” (Wehtje, 170).

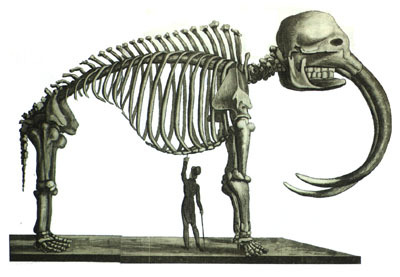

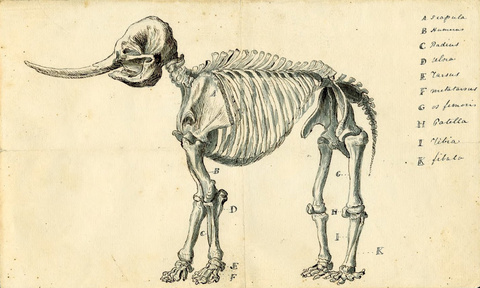

The Mastodon

The mastodon skeleton was the highlight of Peale’s museum. It was exhumed in 1801 in New York by Peale himself and was the center of attention at Philosophical Hall (where Peale relocated his museum in 1794, due to lack of space in his home). For any missing components of the mastodon, Peale painstakingly created paper maiche models of the bones. The massive skeleton had its own exhibition room and visitors were charged a separate entrance fee of fifty cents to enter the exhibit. “Eventually one of Peale’s best-known paintings, a grand and detailed picture of the exhuming operations, was placed behind the mastodon and excited considerable attention itself” (Wehtje, 170).