Peale and Happiness

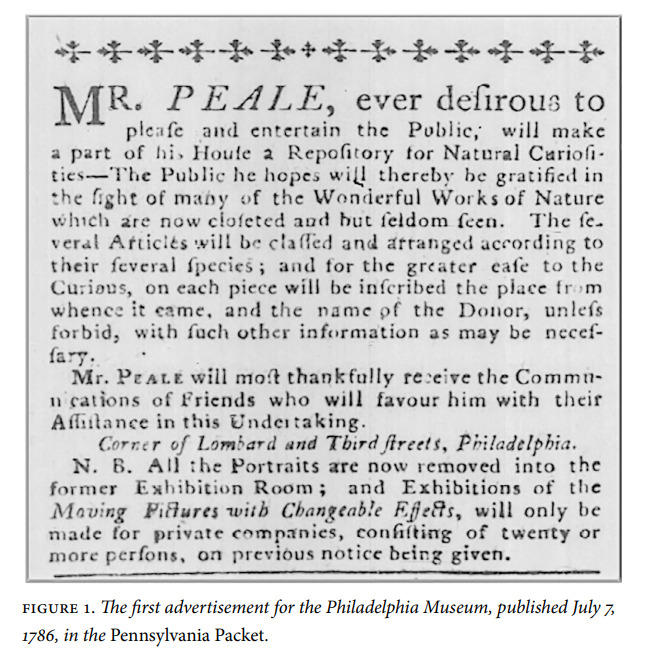

As Peale made the public decision to retire from painting to focus solely on his museum, he was now able to carry through with his Enlightenment virtues of finding beauty in the natural world and sharing it with the public. To be clear, Peale had no formal education in the sciences. “Instead, in a good eighteenth-century manner, he seems always to have assumed that he could learn whatever it was necessary for him to know for this or any other enterprises” (Schofield, 23). And ever the curious man, Peale did just that.

For Peale, the incorporation of science and the naturalistic world was a vehicle for more than simply knowing nature more fully. Rather, he wanted natural history to make people feel differently. For Peale “…carefully framed scientific experiences in terms of aesthetic and social harmony. As Peale rhetorically turns natural objects towards forms of feeling, early American happiness emerges as not only an objective or ‘pursuit’, but also a thing to be collected, displayed and beheld” (Ross, 741).

|

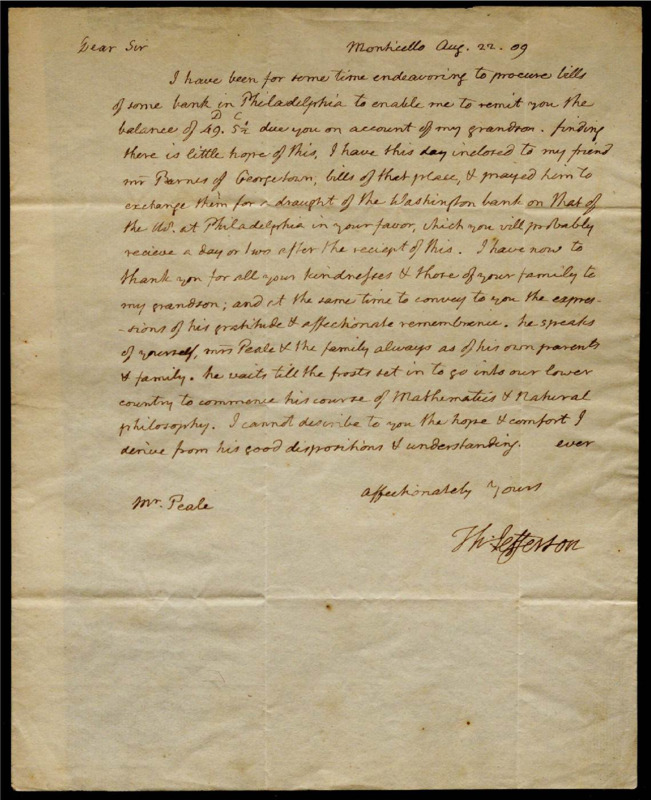

Monticello Aug. 22 .09 Dear Sir I have been for some time endeavoring to procure bills of some bank in Philadelphia to enable me to remit you the balance of 49 D. 5 1/2 C due you on account of my grandson. Finding there is little hope of this, I have this day inclosed to my friend mr. Barnes of Georgetown, bills of that place, & prayed him to exchange them for a draught of the Washington bank on that of the US at Philadelphia in your favor, which you will probably receive in a day or two after the reciept of this. I have now to thank you for all your kindnesses & those of your family to my grandson; and at the same time to convey to you the expressions of his gratitude & affectionate remembrance. He speaks of yourself, mrs. Peale & the family always as of his own parents & family. He waits till the frosts set in to go into our lower country to commence his course of Mathematics & Natural philosophy. I cannot describe to you the hope & comfort I derive from his good dispositions & understanding. Ever affectionately yours Th: Jefferson Mr. Peale |

Simply put, the relationship between the feelings of happiness and scientific objects was in fact a tangible concept in which Peale subscribed. This relationship between science and happiness might seem foreign to us now, but during the Enlightenment of the 18th century, happiness had a much more expansive meaning, and not a tangible emotion we think of today. “A society was happy when its people enjoyed the security, stability, and peace that allowed them to prosper” (Winterer, 3). Furthermore, citizens sought both public and private happiness, for “the science of social happiness” included “many realms of knowledge-nature, religion, art, literature, and politics- awaited exploration” (Winterer, 3). According to Peale’s 19th century lectures, he emphasizes the usage of negative aesthetic terms when describing nonhuman subjects in nature, and how Peale made the conscious choice to find the beauty in everything in the natural world (Ross, 744).

It is with this concept that Ross maintains Peale’s goal was to improve the visual habits of Americans by helping them look at the natural world differently. Ross consults several books on the subject of happiness during the 18th and 19th century in America and finds that happiness was an expectation of citizens and while it could be obtained in various ways, Peale’s belief that “the comfort, happiness, and support of all ranks, depend upon their knowledge of nature” (Ross, 750). Ross further explains how Peale took these ideas and incorporated them into his method of display in his museum, demonstrating Peale’s belief that how we see items, can have an effect on how well we understand the suggested message.

"The public must learn to share his own sense of the importance of natural history, seeing the Diety through His works, and learning to live in health and peace with the Creator's design. Education was his key to success, and 'rational amusement' his means of achieving it. It was compounded, this first popular museum of science, from the artistic skills and the scientific innocence of a self-declared 'citizen of the world'" (Sellers, 27).