Post-Modern Antisemitism Historiography

By the 1890s the Christian imagery of the Jew was so much a part of the general American culture that it could easily by exploited by any dissatisfied group seeking a scapegoat for its ills.

As historians in the 1970s began using a wider variety of sources including newspapers, popular books, and textbooks, they have found that a strong current of deicide and religious antisemitism existed in the United States even when Europe’s antisemitism transformed into racial antisemitism. According to Robert Rockaway and Arnon Gutfeld who trace the history of antisemitism in the 1800s in “Demonic Images of the Jew in the Nineteenth Century United States,” religious antisemitism remained strong because American national identity was tied to being a Christian nation. The American public school, particularly with its use of the McGuffey Readers, advanced the “goal of creating an American national identity” which in practice meant “Protestant religious values and moral principles.”[1] As such, the McGuffey Readers, which had sold 46 million copies by 1870, discredited Israel and Judaism, and blamed Jews for the torture and death of Jesus.[2]

In The Tarnished Dream: The Basis of American Anti-Semitism, Michael Dobkowski breaks from the historiography of the 1950s that deemphasized anti-Semitism or relegated it to the 1890s alone. Dobkowski differentiates between multiple kinds of anti-Semitism. Religiously motivated anti-Semitism charged Jews with deicide while at other times Jews were identified “with an excessive participation” in illegal activity, notwithstanding facts.[3] When Jews were identified with crime it was as the Shylock manipulating money and preoccupied with materialism. Jews were also seen as the parvenu, the perpetual wandering alien who infiltrates society.[4] The idea that Jews were tied together alienated from the national culture made it very easy for many to believe that they were united together in conspiracy. Tangential to that was the corollary that Jews due to their alien, international status were revolutionary radicals (in contradiction to the House of Rothschild charge). Jews were seen as “the quintessential alien, part of a community of strangers, determinedly different” and they were targeted for suspicion because of their role of merchant and moneylender.[5]

Louise A. Mayo argues that the “biformities” in American culture created a complex and ambivalent contradictory image of Jews. According to Mayo, the arrival of Russian Jews in the 1890s was the first major change in anti-Semitic imagery due to concern over their ability to assimilate. Mayo notes that the contradictory ambivalent attitude continues in the 1890s, but the rise of international financial conspiracy thinking begins to permeate American anti-Semitism. In the West, with a small Jewish population, fear of the control of Eastern cities over finance became linked to anti-Semitism. The Populists, Mayo argues, which have been the subject to ongoing debate regarding their role in perpetuating anti-Semitism also were divided in its attitudes toward Jews.[6]

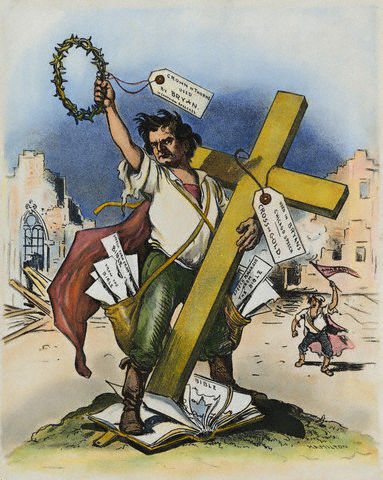

Racial anti-Semitism, according to Rockaway and Gutfeld, is introduced into American culture in the late 1800s when the publisher Telemachus T. Timayenis published three books peddling “a vicious brand of anti-Semitism that mixed ancient lies, demonic imagery, and jingoism into an attack on America’s Jews.”[7] Rockaway and Gutfeld note that anti-Semitism increases following the Civil War due to the rise of several factors: Jewish immigration from southern and eastern Europe made Jews more visible throughout the country, the relative economic success by Jewish immigrants made them the target of envy, ongoing economic crises, and lastly the rise of an agrarian Populist movement against Wall Street. All of these factors contributed to an increase in antisemitic demonization, but it was still centered on deicide. Rockaway and Gutfeld state “By the 1890s the Christian imagery of the Jew was so much a part of the general American culture that it could easily by exploited by any dissatisfied group seeking a scapegoat for its ills.”[8] The series of economic and agricultural depressions made it easy for Populists to “suggest that it was these unseen Jews who were responsible for the farmers’ financial difficulties” and in doing so they linked the religious tropes with the gold standard versus free silver issue into a Jewish financial conspiracy.[9] Even William Jennings Bryan who was not antagonistic to Jews, according to Rockaway and Gutfeld, used the crucifixion metaphor in his most famous speech.[10]

[1] Robert Rockaway and Arnon Gutfield, “Demonic Images of the Jew in the Nineteenth

Century United States.” American Jewish History (vol. 89, no. 4, December 2001) 361.

[2] Ibid, 362.

[3] I Michael N. Dobkowski The Tarnished Dream : the Basis of American Anti-Semitism

(Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1979) 69.

[4] Ibid, 61.

[5] Ibid, 14-15.

[6] Louise A. Mayo The Ambivalent Image : Nineteenth-Century America’s Perception of

the Jew. (Rutherford N.J: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1988) 184.

[7] Robert Rockaway and Arnon Gutfield, 378.

[8] Ibid, 379.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid, 381.