Vessels of Memory

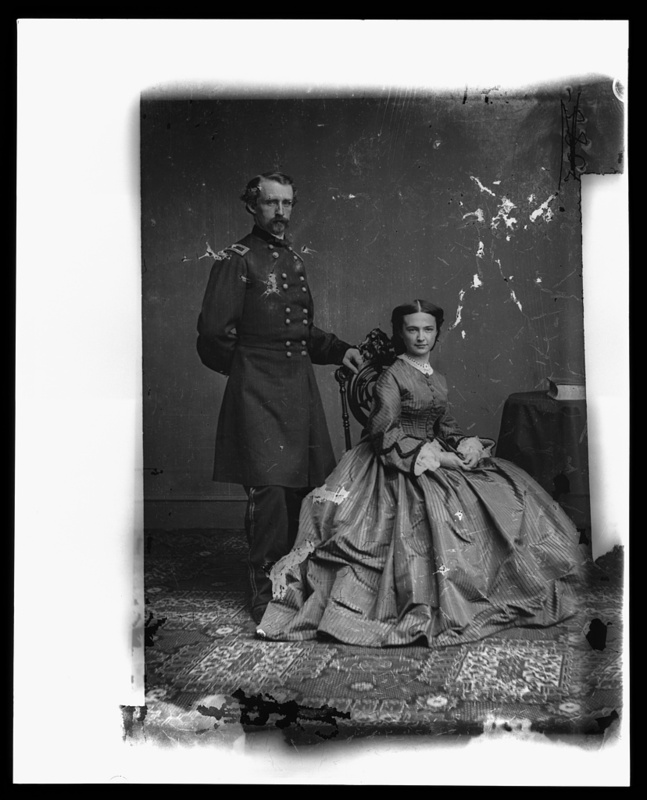

Officers’ wives contributed a considerable amount to current historical understanding about daily life, society, and gender norms on frontier forts in the post-Civil War period. Their higher social status, better education, and access to domestic helpers freed them to commit considerable time to writing correspondence. Without knowing it, letters from women like Alice Grierson and Frances Roe constructed for their future audience vivid imagery of the rich dramas playing out in their lives. Unlike other wives, Elizabeth Bacon Custer (pictured, left) offered windows to the past via memoirs. Motivated by the desire to redeem her husband’s image after his defeat at Little Bighorn, Mrs. Custer wrote extensively about his accomplishments and their life together. Despite this agenda, she is aware of her work’s importance for posterity – as the frontier recedes into the past, testimonies like hers will serve as figurative landmarks.1

However, the sources’ value must be balanced against issues with their reliability. Letters published in many collections were curated by none other than the officers’ wives themselves: whatever world is presented to the reader is, in effect, a censored or idealized version. Less flattering accounts may have been removed to protect one’s image, or embellishments may have been added to enhance the author’s reputation. Even Frances Roe’s admission to omit “all flowery descriptions” in favor of “simple, concise narration” indicates tampering. From a purely historical view, benign intent to improve readability is a poor excuse to edit original material.2 More troublesome are Mrs. Custer’s memoirs. All three books she published – Boots and Saddles (1885), Tenting on the Plains (1887), and Following the Guidon (1890) – were written almost entirely from her memory alone. Building reliable histories requires a firm, factual basis; unfortunately, she dismisses the need for evidence as cumbersome.3

"I greatly regret that I did not [keep a journal], for if I had I would not now be entirely without notes or dates and obliged to trust wholly to memory for events of our life eleven years ago." - Elizabeth Bacon CusterDespite some limitations, these letters and memoirs best help us understand how these women navigated the worlds in which they lived. Certainly, they chronicle women’s day-to-day activities which can be corroborated and supported by official military or government documents. But more importantly, the collected documents are the most reliable sources regarding how societies, value systems, and gender dynamics evolved in the frontier. Taken altogether, officers’ wives and their literate contemporaries served a most vital role as living vessels of frontier memories. These women processed the history unfolding around them, and they distilled their experiences into tangible, transmissible, and relatable memories for future generations.

1 Elizabeth Bacon Custer, Boots and Saddles, or Life in Dakota with General Custer (Santa Barbara, CA: Narrative Press, 2001), 3.

2 Frances M.A. Roe, Army Letters from an Officer’s Wife, 1871-1888 (New York, NY: Appleton, 1909), xv.

3 Elizabeth Bacon Custer, Tenting on the Plains, or General Custer in Kansas and Texas (Norman, OK: Webster, 1887), 38.