Religion & Music in the Election of 1800

In 1800, the United States was fundamentally a Christian nation, albeit one with a multitude of different denominations. So it comes as no surprise, religion played a role in the election. Jefferson’s views on religion were well known. He was a deist, somewhat out of the mainstream, and did not often attend church proceedings. The Federalists hoped to use that against him. Adams had a more conventional religiosity. In general, the Federalist Party as political tended to value religion, tradition, and family authority as a means fostering social, economic, and political order. Republicans, on the other hand, viewed religion as a matter of personal choice, and disfavored establishment churches.

Religious issues against Jefferson were particularly prominent in Connecticut. One particular example of how this played out is a prominent Congregationalist and the Yale President, Timothy Dwight, often referred to as the “Pope of Connecticut”, about whom a Federalist leader noted “Dr. Dwight is here stirring us up to oppose the Demon of Jacobinism”, an obvious reference to Jefferson.[1] Another example, in which Jefferson is accused of being an atheist (among other characterizations), appears in the Connecticut Courant in the form of a question: “Do you believe in the strangest of all paradoxes—that a spendthrift, a libertine, or an atheist is qualified to make your laws and govern you and your posterity?”

But the Federalists may have overplayed their hand using the religious card. A successful Republican counter was to link public support of civil religion by Federalists to their propensity towards authoritarianism and lobbying for national days of prayer and fasting. Later in life, Adams complained “The secret whisper ran through all the sects, “Let us have Jefferson, Madison, Burr, anybody, whether they be philosophers, Deists, or even atheists, rather than a Presbyterian President’ “, referring to a denomination to which many Federalists joined, but not Adams.[2]

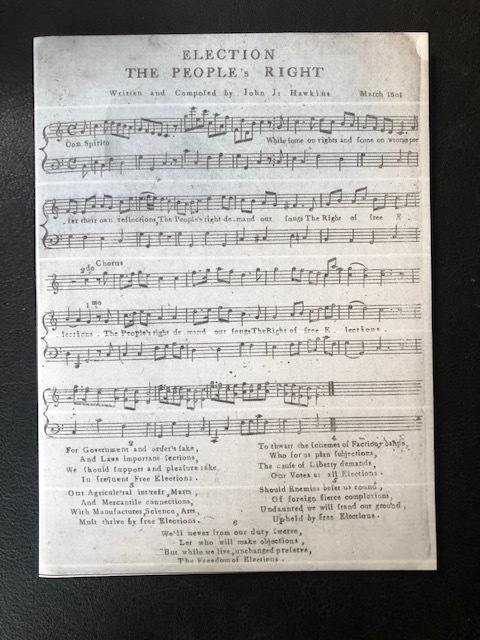

Music was also specially composed to advocate on behalf the candidates. One example, a song written to celebrate “Jefferson and Liberty”, became an instant folk standard: The gloomy night before us flies, The reign of Terror now is o’er.[3] Another campaign ditty, referring to the Alien and Sedition Acts, ends with a similar conclusion: Rejoice, Columbia's son rejoice, To tyrants never bend the knee, But join with heart and soul and voice, For Jefferson and liberty, From Georgia up to Lake Champlain, From seas to Mississippi's shore, Ye sons of freedom loud proclaim, THE REIGN OF TERROR IS NO MORE.[4] After the election, songs and music were also composed to celebrate the election of Jefferson; an example is the “Election The People’s Right” written and composed by John J. Hawkins.

Visible signs of political rivalry were everywhere for people to witness. Republicans wore the French red, white and blue tricolor, while Federalists donned black cockades.

[1] Larson, Magnificent Catastrophe: The Tumultuous Election of 1800, America’s first Presidential Campaign, page 169

[2] Larson, Magnificent Catastrophe: The Tumultuous Election of 1800, America’s first Presidential Campaign, page 177

[3] Davies, et al, America at the Ballot Box : Elections and Political History, Page 13

[4] Brodie, Thomas Jefferson: An Intimate Biography, pp. 324-325