Ensuing Electoral College Vote

In the 1800 election, the Republican Party slate was Thomas Jefferson for President and Aaron Burr for Vice President; the Federalist Party slate was John Adams for President and Charles C. Pinckney for Vice President. Electors, however, could vote for anyone and were not limited to the party candidates. Pursuant to the 1787 Constitution, a total of 138 electors from all 16 states met on December 3, 1800 to cast each of their two votes for any of the respective candidates (or anyone else they wanted); no duplicate voting by each individual elector and only one of which could be for a person from his state. The candidate with the largest number of electoral votes would become President (provided that it was a majority of the total number of electors) and the runner up would be the Vice President.

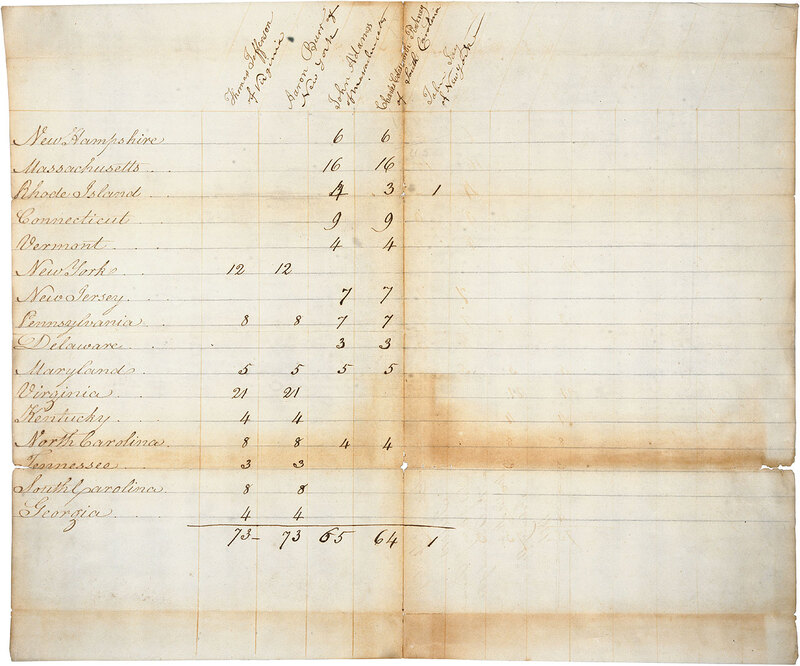

As the original tally sheet recording votes cast by the members of the Electoral College in 1800 shows:

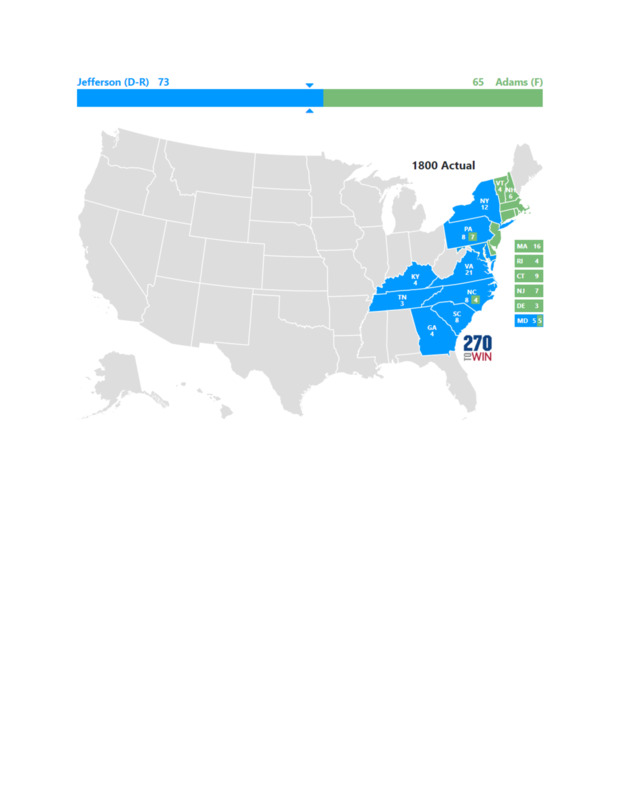

- Seven states supported the Federalist ticket (all but two from New England): Connecticut, Delaware, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont.

- Six states (all but one from the southern region) supported the Republican ticket: Georgia, Kentucky, New York, South Carolina, Virginia and Tennessee.

- Three states split their votes: Maryland, North Carolina and Pennsylvania.

Votes cast were: 73 for Thomas Jefferson, 73 for Aaron Burr, 65 for John Adams, 64 for Charles Pinckney and one for John Jay.

But the Republicans had a problem. Unlike the Federalists, who arranged for one of their electors to cast one of their electoral votes for someone else besides its candidate for President (in this case it was cast for John Jay), the Republicans failed to do something similar. Jefferson had written to Burr urging him to do so. Burr never responded, and in fact, urged every Republican elector to cast a vote for him.[1] One Federalist surmised that no Republican elector could afford to drop his vote because they all presumed that at least some of their party would be disloyal and fail to deliver their vote for Jefferson.[2]

Although the election was close, it was clear that the Republicans had won the election. Their candidates receive a high proportion of the popular vote and more electoral votes than the Federalists. What was not clear was which man would be the President: Jefferson or Burr. Both had received the same number of elector votes. The choice between them would now go to the House of Representatives to decide. Under the 1787 Constitution, a tie was to be broken by the special House of Representatives procedure in which each state had one vote determined by a majority vote of each state legislature and a majority of all states was required.

In the House, the Republicans controlled eight state delegations (Georgia, Kentucky, North Carolina, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia and Tennessee), the Federalists controlled six delegations (Connecticut, Delaware, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and South Carolina) and two delegations were deadlocked (Maryland and Vermont). Neither party had the nine votes necessary to elect the President since the Federalists preferred Burr over Jefferson. Mainly because most Federalists could not abide having Jefferson as President.[3] Although Burr could have stepped aside, he chose not to, in spite of entreaties from Jefferson and others to do so. Burr was self-serving and ambitious, and continued to argue that the Federalists would be in a better position if they supported him for President.[4]

Many different trial strategies were proposed to break the deadlock, but in the end, it was Hamilton who crafted a solution.[5] In a choice between Jefferson and Burr, he preferred the former; despite his party shifting their support to Burr. He further proposed some modest policy assurances be obtained from the in-coming administration to continue certain Federalist polices. When the sole House representative from Delaware received such assurances, he announced he was changing his vote, and this action broke the deadlock. On the 36th and last vote, ten states voted for Jefferson, four against him (Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Rhode Island) and two abstained (Delaware and South Carolina). And then the 1800 Presidential election was finally over.

[1] Larson, Magnificent Catastrophe: The Tumultuous Election of 1800, America’s first Presidential Campaign, page 243

[2] Freeman, Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic, Page 242

[3] Freeman, Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic, Page 242

[4] Foley, Edward B. Presidential Elections and Majority Rule, Page 25

[5] Ferling, Adams vs. Jefferson : The Tumultuous Election Of 1800, Page 176 ff