The Traveler

Emma Hart Willard, was born in Berlin, Connecticut on February 23, 1787. Willard's parents were prosperous farmers, and represent the burgeoning "middle class" of the late-18th and early 19th century Americans.

Willard’s parents championed her schooling and acquirement of knowledge. As many middling class young women did, she first went to a district school and an academy in Berlin, and subsequently two schools in Hartford for the domestic arts, giving their daughter the education of what would have once been considered only for the genteel elite. This practice became more common in the 19th century, as industrial improvement led to cheaper goods, more steady salaries, and development of common schools.1 Her father was a fervent Jeffersonian and Universalist, believed in the universal principle of egalitarianism, and clearly instilled that logic in his daughter.2 While at school, Willard soon discovered her new role in society: champion of women’s education. She believed the “peculiar organization of [her] mind,” and her “inward fires,” to be the force behind her fervent fight for equal education amongst the sexes.3 Her goal throughout her early decades as a teacher was to establish publicly funded female “seminaries,” so necessary to provide education for all women, regardless of wealth and status in society. She borrowed from the classic school of thought initially proposed by Benjamin Rush forty years prior: that education for all women subsequently benefits the entire community.4 If women are educated in all subjects, they will pass that knowledge along to their children, developing the future generations of the American republic.5

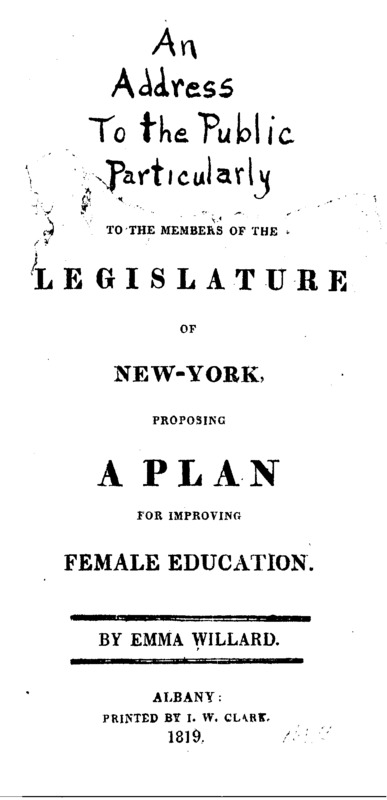

Willard and her husband formally submitted A Plan for the Improving of Female Education, to the New York Legislature in 1819, the first official appeal to the government for universal education in the state of New York. While ultimately not successful on a broad scale, she did achieve a charter for one female seminary, in Waterford, New York. It was there that Willard began her long journey as the head of one of the first in America. Her focus was developing talented teachers to further societal improvement. She flourished in her role, moving the seminary to Troy, and developed a hybrid curriculum, which balanced between the traditional ornamental skills of art, music, and exercise, but also included college level mathematics, philosophy, and the sciences. Her curriculum, though it did not ultimately advance towards an official degree, became highly renowned and her teachers well respected.6

In 1829, Willard decided, with expansion of her own worldview and curriculum in mind, to travel to England and France. She wanted to view the countries she’d written about in her famous textbook, A History of the United States, or Republic of America, which was highly esteemed for its situating America within the broader context of the Atlantic world – somewhat of a rarity for the burgeoning nationalism of the period.7 See the page on Willard’s purpose of her tour for more information on her journey, and what she did after her return.

Willard lived until 1870, after a long life of distinguished work.

1. Richard Bushman, The Refinement of America (New York: Knopf, 1993), 208.

2. Though the Democratic, or Jeffersonian ideals of utopian egalitarianism championed rights for "all," this traditionally was not meant to include women, or people of color. See: Seth Cotlar, Tom Paine's America: The Rise and Fall of Transatlantic Radicalism (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2011) for more information on the developing partisan ideas.

3. Anne Firor Scott, "What, Then, is the American: This New Woman?" The Journal of American History 65, no. 3, (Dec. 1978), 684.

4. Dr. Benjamin Rush’s speech, “Thoughts Upon Female Education Accommodated to the Present State of Society &c., (Philadelphia: Printed by Prichard & Hall, 1787), laid the framework for future education for both young women and men. This speech, originally given at the first board meeting of the Young Ladies’ Academy in Philadelphia in 1787, argued that women should be educated not only in ornamental skills, but also in the principles of liberty and government. He believed these skills were necessary to teach future generations, as “the first impressions upon the minds of children are generally derived from women.”

5. See Linda Kerber’s Women of the Republic, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1980), and Mary Beth Norton’s Liberty’s Daughters (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1980), for the foundational scholarship on “republican mothers.

7. Susan Grigg, "Willard, Emma Hart (1787-1870), educator and historian," American National Biography, 1 Feb. 2000.