The vision of Spencer Baird for the Smithsonian Institution

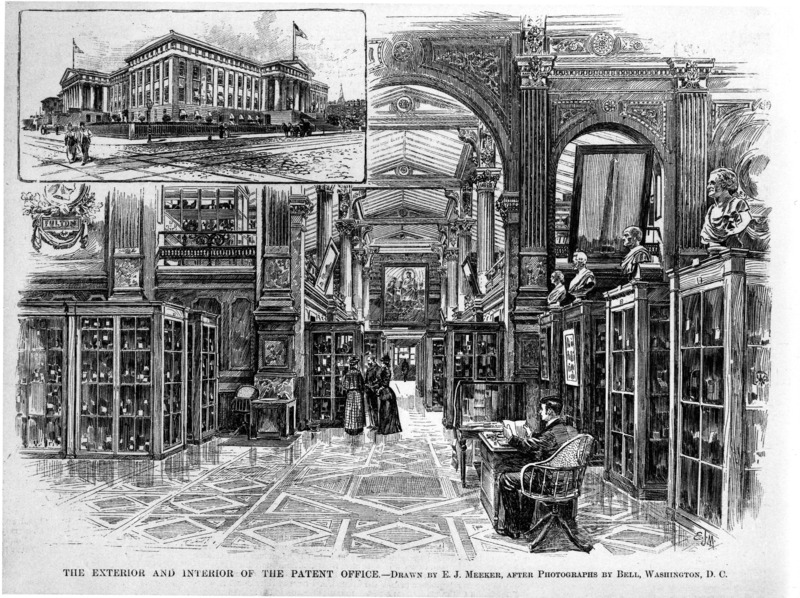

In addition to collections of books, there were also collections of things; of artifacts, plants, birds, maps and charts from previous US government sponsored expeditions. For example, the voyage led by Charles Wilkes from 1838-1842 had brought back thousands of carefully curated treasures, which were then displayed at the US Patent Office. There were advocates who believed that collections of natural history should be placed under the purview of the newly created Smithsonian Institution. However, Joseph Henry was wary, concerned that it would cost too much money to care for these collections, and did not want to see the Smithsonian become the nation’s attic. Still, his first hire in 1850 was for an assistant secretary and the first curator to oversee the natural history artifacts, Spencer Baird.

Spencer Baird was drawn to studying and collecting nature from an early age, making connections with other naturalists, including well known ornithologist John James Audubon. He firmly believed in the significance of preserving natural artifacts in the case of their possible extinction, and for the purpose of research. In fact, he was so interested in natural history collections that in 1842, he walked from his home in Carlisle, Pa, all the way to Baltimore, Md, where he took a train to Washington, DC in order to see the Wilkes Expedition exhibit on display at the US Patent Office. He was teaching natural history at his alma mater, Dickinson College, when he heard of the founding of the Smithsonian Institution in 1846, and wrote to Secretary Henry expressing an interest in overseeing the natural history collections. As much as Henry was reluctant to acquire items, possibly squandering money that should be used to fund scientific research, collections of historical relics, works of art, and scientific artifacts continued to amass at the Smithsonian. As a result, the Smithsonian was slowly turning into a national museum, based on popular interests that were at odds with Secretary Henry’s narrow vision of how to ‘increase’ knowledge. Baird would have to wait a few more years before Henry finally brought him on board.

A prolific writer, Baird was accustomed to sending as many as ten letters a day. In a letter to his mentor George Perkins Marsh, a member of The Board of Regents, Baird revealed his life’s dream, writing in 1853 that his desire was to be the director of a national museum ; “I expect the accumulation of a mass of matter thus collected (which the Institution cannot or will not ‘curate’ efficiently) to have the effect of forcing our government into establishing a National Museum, of which (let me whisper it) I hope to be director. Still even if this argument don’t weigh now; it will one of these days and I am content to wait (Baird, siarchives).”