Warren and Wright: Their Lives

Mercy Otis Warren was born in Barnstable, Massachusetts on September 25, 1728. Her father, Colonel James Otis, was both a farmer and a militia officer. Like many girls during her time, she did not receive a formal education. However, unusually, at her request and with the permission of her father, she was allowed to participate in the formal lessons being taught to her brother James Otis. She was raised in a Puritan family which kept fairly traditional gender roles for the time.[1] Therefore, as her mother’s eldest daughter, Mercy was also expected to focus on domestic responsibilities and step in as her mother’s assistant when she was incapacitated by pregnancy, childbirth, post partum, etc. She married James Warren, a farmer and politician, on November 1754 and subsequently gave birth to the couple’s five children. The family lived in Plymouth, Massachusetts where she resided until her death October 19, 1814.

Mercy Otis Warren, through both her actions and her relationships, was regularly present in the political and public realm. She maintained a lifelong friendship with Abigail Adams, and regularly corresponded with both her and her husband John Adams (though the two did have a falling out due to one of Mercy’s writings, but later reconciled.) With the support of her husband, throughout her life, despite such restrictions against the behavior, Warren remained politically active through her many published writings. Her first published work, Adulateur: A Tragedy: As it is now Acted in Upper Servia a play, was printed in 1772 in The Massachusetts Spy newspaper. She continued to write and publish regularly in her own name (unlike many of her female contemporaries) and consistently pushed pro-republican ideas such as liberty from tyranny. She railed against the British government and, later, opposed the adoption of the Federal Constitution. Her most prolific work, a comprehensive work of history on the American Revolution titled History of Rise, Progress and Termination of the American Revolution, was published in 1805 and would serve as the reason for the rift with John Adams. Her writings showed a woman who understood and “accepted without question the existing gender status quo”[2] though she often “struggled with the propriety of a woman writing about politics.”[3] In the end, she believed that women, as mothers and wives, had a purpose and stake in the political realm and, through their domestic roles, should play a part in protecting what was important (i.e. their families, homes, and country).[4]

[1] Rosemarie Zagarri, A Woman’s Dilemma: Mercy Otis Warren and the American Revolution (Somerset: Wiley, 2015) 9 "Although hierarchical and patriarchal in structure, the Puritan family also assigned a dignified place to women. As wife and mother, the woman was regarded as the husband’s essential friend, companion, and helpmeet. While she must defer to her husband, she had a particular realm of authority of her own – the household.”

[2] Zagarri, 10.

[3] Zagarri, 70.

[4] For a more in-depth biography see “Warren, Mercy Otis (1728-1814), Poet and Historian of the American Revolution,” American National Biography. For an even more extensive biography see Rosemarie Zagarri, A Woman’s Dilemma: Mercy Otis Warren and the American Revolution (Somerset: Wiley, 2015).

Frances “Fanny” Wright was born in Dundee, Scotland on September 6, 1795. Her father, James Wright, was a linen merchant who passionately supported the works of Thomas Paine. Both her parents died when she was three, forcer her younger sister Camilla to be moved to England to reside with their maternal family. She spent time growing up in London where she witnessed the distinction between poor and wealthy which would later direct the course of her beliefs and work. The two girls left England in 1813, when Fanny was eighteen, moving back to Scotland with her uncle James Mylne, a professor at the University of Glasgow who regularly voiced his avid opposition to the slave trade. Five years later, Fanny and Camilla traveled to America, visiting a variety of places in the Northeast so as to get a feel for the land. Fanny quickly fell in love with America which served as the subject of one of her earliest works Views of Society and Manners in America which was published in 1821 and offered high praise of the new nation. Through her writings and relationships, she too was well connected, eliciting praise from Thomas Jefferson and forming a long-term friendship with the Marquis de Lafayette.

Wright spent her life fighting for the things she believed in; most notably against slavery. In 1825, she purchased a large portion of land and a several slaves in an effort to prove that with education and opportunity, the people who were enslaved would work towards the goal of their own freedom. During the same period, she co-edited a newspaper, The New Harmony Gazette, with her close friend Robert Dale Owen. The paper published many works by Fanny herself as well as others promoting the same ideas including anti-slavery and a progressive ideal of a utopian society. In the end, through the “alleged improprieties”[1] of her foreman, her settlement failed; though that did not stop her desire to preach publicly about her more radical ideals. On July 4, 1828, she spoke publicly in front of a mixed audience of men and women (probably one of the first women to do so) touting anti-slavery, anti-religion, anti-marriage, and the autonomy of women. She continued to travel through the Northeast giving a series of speeches which drew large crowds, though she regularly received derision and very little support from even the more progressive women of her time.

Despite her beliefs in the independence of women, her life played out very differently. During a visit to Haiti in 1829, she began a sexual relationship with William Phiquepal d'Arusmont, a French physician, and became pregnant. In order to legitimize the child, Wright felt obligated to marry d'Arusmont in 1831. Living in Paris with her new husband, Wright was unable to participate in her political and public life. She suffered the loss of a second child and eventually made her way back to America to continue her work, purchasing a church which she converted into a public space she named the “Hall of Science.” By then, however, she had lost much of her vigor and could not entice audiences in the same manner. She eventually went back to France, where she struggled both personally and financially. In 1850, d'Arusmont sought a divorce through which he retained full custody of their daughter as well as took ownership of property that had been brought into the marriage by Wright. Without family or finances, she returned to America, dying in Cincinatti, Ohio on December 13, 1852.[2]

[1] “Wright, Frances (1795-1852), Reformer and Author.” American National Biography.

[2] For a more in-depth biography see “Wright, Frances (1795-1852), Reformer and Author.” American National Biography. For an even more extensive biography see Eckhardt, Celia Morris. Fanny Wright : Rebel in America. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992.

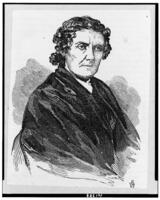

Frances Wright d'Arusmont

One of the only surviving likenesses of Frances Wright in her later years.