Mercy Otis Warren and Frances Wright: A Polarizing Difference

While both women certainly have impacted both feminism and history itself, it is clear that they differed in their opinions on how women could and should participate in the public sphere and how their contemporaries and modern historians have viewed their contributions. In her time, as well as ours, Warren was not considered a radical. She clearly believed women’s rights were a facet of the rising American Republicanism and women’s roles (both public and private) should remain tied to the family and more traditional domestic responsibilities. Fanny Wright, however, believed that women should not be hindered by marriage, motherhood, or other constraints and should stand as individuals in the cause of human liberty. While most historians agree that Warren served up a brand of feminism that could be tolerated and embraced by her contemporaries, they are not so inline when discussing Fanny Wright; her very radicalism has provided fodder for modern historians to continue to question her influence.

What mostly, however, sets these two women apart is how they believed women fit into the grand scheme of society as a whole. Warren felt that a woman’s role within the family unit was fundamental to the success of society. She believed that while women could, when necessary, speak out publicly about politics, particularly if it threatened the foundation of their families. However, it was in their role as a cog in the communal family unit where their dedication to the cause should lie. She maintained that this unit was the most important aspect of society and should be prioritized above all else. In contrast, Wright thought that women were singular individuals in and of themselves. She felt that women not only had a right, but a responsibility to fight for a better society and to share equally in status and stature with men. She avidly opposed the idea that women should be defined by their roles as mother or wife, nor even as a part of organized religion. She believed that women were fundamentally equals to men and should share in the rights and responsibilities that came with that equality. In their contrasting self-identifications Warren saw herself as part of a familial collective identity while Wright saw herself as a strictly individualistic identity; though both expected other women to follow suit.

Despite this underlying disagreement, it is very clear that both women clearly had some impact on the early feminist movement and helped clear the path for other women to move into the public and political realm that had been previously occupied only by men. With further research into both how these women portrayed themselves publicly and how their behavior was seen by their contemporaries, we can attempt to understand a broader picture of how women came to eventually be fully active within the public sphere. By laying the early groundwork for these later feminists, both Mercy Otis Warren and Fanny Wright showed that not only was a woman capable of being publicly active, it was, in fact, a woman’s responsibility to step outside the standard acceptable behavior to do so. While Warren certainly felt that women should incorporate their desire for political action into their motherhood and Wright clearly disagreed, both women readily acknowledged that women had an imperative to activate themselves in some public way for the good of all mankind and both sought to do so in their own way.

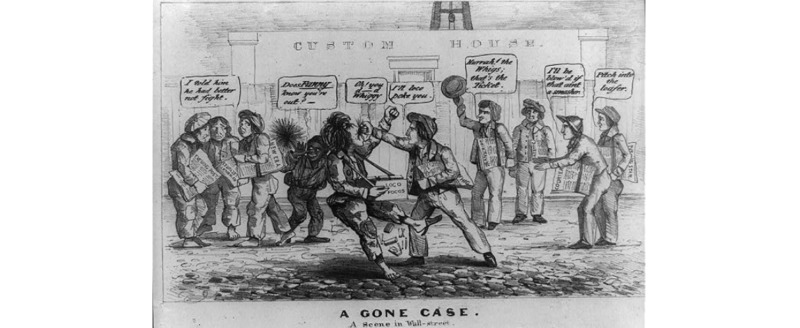

A gone case. A scene in Wall-Street

A cartoon printed in 1850 depicting "the Whigs and the radical Democrats (or ‘Loco Focos’), as scuffling newsboys. On the left three of the newsboys hold Democratic newspapers the "New York Evening Post" and the "New Era," and a copy of radical reformer Frances (‘Fanny’) Wright's lectures. The chimney sweep taunts them, "Does Fanny know you're out?" On the right, a second group of newsboys, holding copies of Whig journals, the "Transcript, Morning Courier and New York Enquirer, Gazette," and the "Evening Star," cheer on the winning fighter.”[1]

[1] “A Gone Case. A Scene in Wall-Street,” image, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, accessed July 12, 2021, https://www.loc.gov/resource/cph.3a09167/.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Beecher, Catharine Esther. Letters on the Difficulties of Religion. Hartford: Belknap & Hamersley, 1836.

D’arusmont, Frances Wright. England, the Civilizer: Her History Developed in Its Principles. London: Simpkin, Marshall and Co., 1848.

“Founders Online: Home.” University of Virginia Press. http://founders.archives.gov/documents//lib/home/home.xml.

Harris, Sharon M, Jeffrey H Richards, and Mercy Otis Warren. Mercy Otis Warren: Selected Letters. University of Georgia Press, 2010.

Hayes, Edmund M. “The Private Poems of Mercy Otis Warren.” The New England Quarterly 54, no. 2 (1981): 199–224.

“The Adams Papers Digital Edition, Massachusetts Historical Society,” 1840 1753. https://rotunda-upress-virginia-edu.mutex.gmu.edu/founders/ADMS.html.

The Plot Exposed! Or, Abolitionism, Fanny Wright, and the Whig Party! The Following Sermon, Delivered at the African Church in Church Street, by the Rev. Moses Parkes, a Colored Preacher from Canterbury, Conn, Drew from Miss Desdamont the Letter, 1838. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbpe.05603500/.

Warren, Mercy Otis. Poems, Dramatic and Miscellaneous. By Mrs. M. Warren. [Two Lines from Pope]. Boston, MA: by I. Thomas and E.T. Andrews. At Faust’s Statue, no. 45, Newbury Street, 1790.

———. The Blockheads, or, The Fortunate Contractor, 1776. https://search-alexanderstreet-com.mutex.gmu.edu/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Cbibliographic_details%7C3609897.

Warren, Mercy Otis, and Lester H. Cohen. History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution Interspersed with Biographical, Political, and Moral Observations. Indianapolis: Liberty Classics, 1988.

Wright, Frances. Course of Popular Lectures as Delivered by Frances Wright with Three Addresses on Various Public Occasions, and a Reply to the Charges against the French Reformers of 1789. Second Edition. New York: Office of the Free Enquirer, 1829.

———. Reason, Religion, and Morals. Amherst, NY: Humanity Books, 2004.

———. Views of Society and Manners in America. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1963.

Secondary Sources

Cohen, Lester H. “Mercy Otis Warren: The Politics of Language and the Aesthetics of Self.” American Quarterly 35, no. 5 (1983): 481–98.

Connors, RJ. “Frances Wright: First Female Civic Rhetor in America.” College English 62, no. 1 (1999): 30–57.

Eckhardt, Celia Morris. Fanny Wright : Rebel in America. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992.

Glicksberg, Charles I. “William Cullen Bryant and Fanny Wright.” American Literature 6 (1934): 427–32.

Hayes, Edmund M. “Mercy Otis Warren versus Lord Chesterfield 1779.” The William and Mary Quarterly 40, no. 4 (1983): 616–21.

Kerber, Linda K. Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America. Chapel Hill, UNITED STATES: University of North Carolina Press, 1980. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/gmu/detail.action?docID=4322176.

Kissel, Susan S. In Common Cause: The “Conservative” Frances Trollope and the “Radical” Frances Wright. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1993.

Norton, Mary Beth. Liberty’s Daughters: The Revolutionary Experience of American Women, 1750–1800. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press, 1996.

Parker, Alison M. Articulating Rights : Nineteenth-Century American Women on Race, Reform, and the State. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2010.

Tarantello, Patricia F. “Insisting on Femininity: Mercy Otis Warren, Susanna Rowson, and Literary Self-Promotion.” Women’s Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 46, no. 1–4 (June 1, 2017): 181–99.

Travis, Molly Abel. “Frances Wright: The Other Woman of Early American Feminism.” Women’s Studies 22, no. 3 (1993): 389–97.

American National Biography. “Warren, Mercy Otis (1728-1814), Poet and Historian of the American Revolution.” Accessed June 22, 2021. http://www.anb.org/view/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.001.0001/anb-9780198606697-e-2001086.

American National Biography. “Wright, Frances (1795-1852), Reformer and Author.” Accessed June 22, 2021. http://www.anb.org/view/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.001.0001/anb-9780198606697-e-1500777.

Zagarri, Rosemarie. A Woman’s Dilemma: Mercy Otis Warren and the American Revolution. Somerset: Wiley, 2015.