Mercy Otis Warren in her Own Words

Mercy Otis Warren wrote both plays and poetry during her lifetime[1], most of which were designed to push a political agenda: pro republicanism and often anti-British. She did so in her own name, as a woman, yet always remained true to what she believed her role as a woman was. In her writings and personal letters she maintained that her political and public work was secondary to her domestic responsibilities and not usually the purview of a woman. She wrote to a friend “no one has at stake a larger share of domestic happiness than myself, and while I feel greatly concerned for the welfare of my country, my soul is not so far Romanized but that the apprehensions of the wife and the mother are continually awake.”[2] She believed that concern for her country and politics took a back seat to her role as a wife and mother. Similarly in a Poem entitled “On Primitive Simplicity” she wrote “Critics may censure, but if candour frowns, I’ll quit the pen, and keep within the bounds, the narrow bounds, prescrib’d to female life, the gentle mistress and the prudent wife.”[3]

In her personal writings, Warren often downplayed the constitution of women as less than that of men and prone to emotional motivation. “[B]ut as our weak and timid sex is generally but the echo of the other and like some pliant piece of clock-work the springs of our souls, move slow or more rapid, just as hope, fear, or fortitude give motion to the conducting wires, that govern all our actions.”[4] She also apologized for what she saw as overstepping the bounds of her domestic role. Writing to John Adams in 1775 she asked “parden for touching on War politicks or anything Relative therto, as I think you gave me a Hint in yours Not to Approach the Verge of anything so far beyond the Line of my sex.”[5] The following year, upon John Adams’s request for her opinion she expressed surprise writing “your asking my opinion on so momentous a point as the form of government which out to be preferred, may be designed to ridicule the sex for paying any attention to political matters.”[6]

Warren did, however, recognize the importance of women and women’s personal stake in the success of the country and government. When writing with women, she often justified her political involvement as a facet of her domestic responsibilities, declaring that it was the nature of her role as a mother and wife that forced her to speak out. Writing to Hannah Winthrop in early 1774: “I determined to leave the field of politicks to those whose proper business it is to speculate and to act at this important crisis; but the occurrences that have lately taken place are so alarming and the subject so interwoven with the enjoyments of social and domestic life as to command the attention of the mother and the wife.”[7] Similarly, writing to Hannah Lincoln later that year: “it would argue great want of candour to think there was not many such (more especially among our own sex) who yet judge very differently with regard to the calamities of our unhappy country…But though every mind of the least sensibility must be greatly affected with the present distress; and even a female pen might be excused for touching on the important subject.”[8] It is clear that despite her misgivings about women taking stake in the public, political world, she believed her convictions to be important enough to support her endeavors and place her beyond concern for reproach. In her 1774 letter to Hannah Winthrop she concluded “As for that part of mankind who think every rational pursuit lies beyond the reach of a sex too generally devoted to folly, their censure or applause is equally indifferent to your sincere friend.”[9]

[1] As an example see Warren, The Blockheads, or, The Fortunate Contractor. 1776.

[2] Mercy Otis Warren to Hannah Winthrop, August 1774. Harris, Richards, and Warren, Mercy Otis Warren: Selected Letters, 31.

[3] Hayes, “The Private Poems of Mercy Otis Warren,” 228.

[4] Mercy Otis Warren to Abigail Adams, December 29, 1774. Harris, Richards, and Warren, Mercy Otis Warren: Selected Letters, 41.

[5] Mercy Otis Warren to John Adams, September 4, 1775. “The Adams Papers Digital Edition, Massachusetts Historical Society.”

[6] Mercy Otis Warren to John Adams, March 10, 1776. Harris, Richards, and Warren, Mercy Otis Warren: Selected Letters, 69.

[7] Mercy Otis Warren to Hannah Winthrop, 1774. Harris, Richards, and Warren, 27.

[8] Mercy Otis Warren to Hannah Lincoln, June 12, 1774. Harris, Richards, and Warren, Mercy Otis Warren: Selected Letters, 29.

[9] Mercy Otis Warren to Hannah Winthrop, 1774. Harris, Richards, and Warren, 27.

The solemnity that covered every countenance, when contemplating the sword uplifted, and the horrors of civil war rushing to habitations not inured to scenes of rapine and misery; even to the quiet cottage, where only concord and affection had reigned; stimulated to obser-vation a mind that had not yielded to the assertion, that all political attentions lay out of the road of female life.

It is true there are certain appropriate duties assigned to each sex; and doubtless it is the more peculiar province of masculine strength, not only to repel the bold invader of the rights of his country and of mankind, but in the nervous style of manly eloquence, to describe the blood-stained field, and relate the story of slaughtered armies.

Sensible of this, the trembling heart has recoiled at the magnitude of the undertaking, and the hand often shrunk back from the task; yet, recollecting that every domestic enjoyment depends on the unimpaired possession of civil and religious liberty, that a concern for the welfare of society ought equally to glow in every human breast, the work was not relinquished. The most interesting circumstances were collected, active characters portrayed, the principles of the times developed, and the changes marked; nor need it cause a blush to acknowledge, a detail was preserved with a view of transmitting it to the rising youth of my country, some of them in infancy, others in the European world, while the most interesting events lowered over their native land.[1]

[1] This small section of Mercy Warren’s introduction to her historical work explains her feelings about her role as an historian and a woman. Warren and Cohen, History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution Interspersed with Biographical, Political, and Moral Observations, xli–xlii.

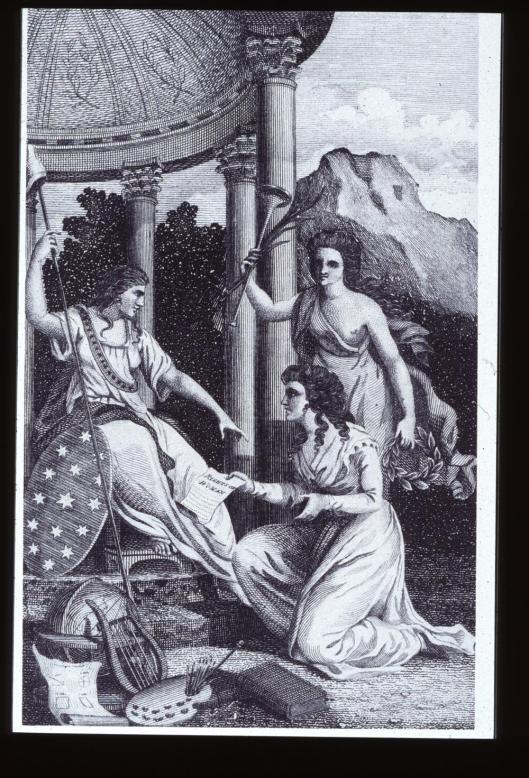

Through literature and the new republicanism, women like Mercy Otis Warren and Mary Wollstonecraft (pictured kneeling), were asserting their authority to have a say into how their lives were overseen. This drawing was the cover for the first journal specifically for women in the United States: The Lady's Magazine, and Repository of Entertaining Knowledge.