Emma Willard's Legacy

"Where England and France excel us here, let us go and be instructed by them; where in these, we are their superiors, let them come and learn of us."

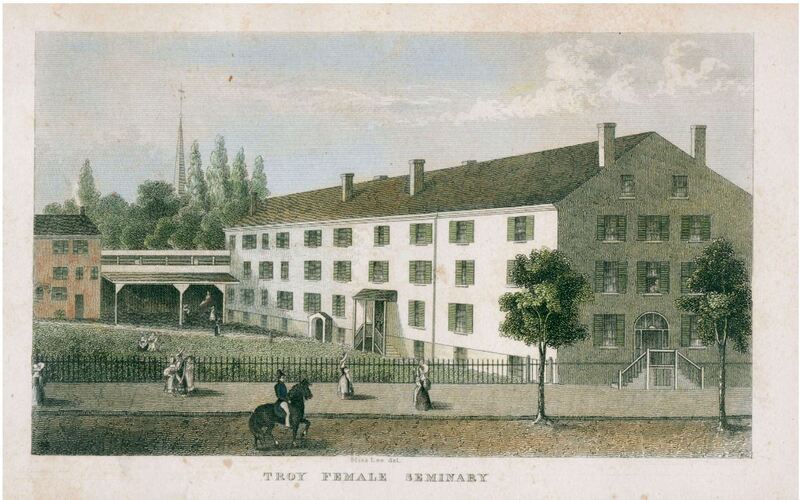

When Emma Willard arrived to Troy Seminary, she was met with great fanfare from her students and teachers. As her young student Elizabeth Cady Stanton, future suffragette and women's right advocate, noted, Willard had a new "profound self-respect (a rare quality in woman) which gave her a dignity truly regal…”1

Willard achieved what she desired, a new outlook on her life and purpose in America. She abolished some preconceived notions, and developed her own opinions on things that once seemed so unique and exciting to her. Her takeway, as summed up in a sentence, was: "Where England and France excel us here, let us go and be instructed by them; where in these, we are their superiors, let them come and learn of us." Willard saw America, Europe, and Great Britain as having strengths that could assist one another, rather than enemies or hierarchical. With the polished continued education from abroad, and the new network of reformers and other women, Willard only gained more footing in America. She continued to further women’s education, successfully establishing her own charity association, through which she developed a system of schooling in Greece in 1837.

Women's education in the nineteenth century developed from ornamental to a more purposeful reason.2 Female academies, which had developed throughout the early-mid nineteenth century, continued to increase. Women's seminaries such as Willard's started to appear across the country, adding in new curriculums found at men's colleges, such as arithmetic, the sciences, and the classics. After her trip to Europe, Willard continued to work on creating new textbooks, and the "researching, revising, and updating occupied much of her time." Some examples textbooks are included below.3 S

Willard's legacy lived on through her current and future pupils, who were inspired by her choices and independence. Willard continued to champion women's education, alongside other reformers such as Lydia Maria Child, Sarah Josepha Hale, and Margaret Fuller. They adapted their views to fit in the context of the broader transatlantic world around them, and with their persistence, furthered the movement of gender equality well into the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.4

1. Susan Grigg, "Willard, Emma Hart (1787-1870), educator and historian," American National Biography, 1 Feb. 2000.

2. Lucia McMahon, Mere Equals: The Paradox of Educated Women in the Early American Republic (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2012), 33.

3. Nina Baym, "Women and the Republic: Emma Willard's Rhetoric of History." American Quarterly 43, no. 1 (1991), 17.

4. Mary Kelley, Learning to Stand and to Speak: Women, Education, and Public Life in America's Republic (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 93.

"This is not so much a subject which I choose, as one which chooses me. It comes unbidden to my mind, and like an intrusive guest, there it will abide, and irresistibly claim my attention."

A selection of Willard's textbooks. Each textbook matches with the map below it.

A System of Universal History, in Perspective Accompanied by an Atlas, Exhibiting Chronology in a Picture of Nations, and Progressive Geography in a Series of Maps

A System of Universal History, published after Willard's return home from her trip abroad, encompasses what Willard considered to be the entire history of man - not only geographic, but the history of nation building, empires, and time itself.

A series of maps to Willard's History of the United States, or, Republic of America. Designed for schools and private libraries.

This atlas, designed by Emma Willard, was a supplement to her textbook The History of America. This is the first edition, which traces the development of the United States through twelve separate maps.

History of the United States, or, Republic of America.

Willard's most famous textbook, The History of the United States, or the Republic of America. This book, first published in 1828 prior to her trip abroad, went through 53 reprintings by 1873, and was translated into German and Spanish. This specific edition includes information on the Spanish American War.

Willard's historic guide. Guide to the Temple of time; and universal history for schools.

This is Willard's later textbook on history and nation building. She includes the Temple of Time infographic within this work.

A selection Willard's maps and infographics are below. Each map matches with the textbook above it.

Picture of Nations, or Perspective Sketch of the Course of Empire

This is an infographic or map tracing the international "course of empires" starting with the Roman Empire up to the empire of Napoleon.

Introductory Map

First map in a series of twelve that accompany Willard's textbook The History of the United States. This map, as Willard writes, shows the "locations and wanderings of the Aboriginal tribes."

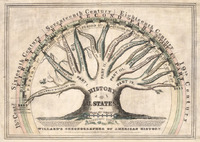

Willard's Chronographer of American History. History of the U. States or Republic of America. Historic Tree, 1845

Willard uses the Historic Tree as a visualization of important events in American history. This is reprinted in smaller form in her textbook History of the United States.

The Temple of Time

Willard's map, the Temple of Time, shows her skills as a cartographer, and the way she believed time was structured. She believed that facts were all connected to one another, and could be stored in the "temple" (or the mind) for future recall. This reflects her curiosity of the antiquities in her time abroad.