Women in the Public Sphere: Mercy Otis Warren and Fanny Wright

Most women in the early American Republic understood that their conscribed place in society was to remain outside the public and political sphere. Yet, there were women who both spoke out and acted out against this conscription in what many historians have seen as highly influential to the early feminist movement. Some did it from within the confines of their wifely and maternal roles; others stood against the mainstream and placed themselves directly in the public eye. By investigating two such women, Mercy Otis Warren and Frances “Fanny” Wright, who appear to stand on the polarities of this early feminist movement, we can attempt to understand how they each felt about women’s participation in the public sphere, how they were influenced by the world around them, and how they each held influence over that same world.

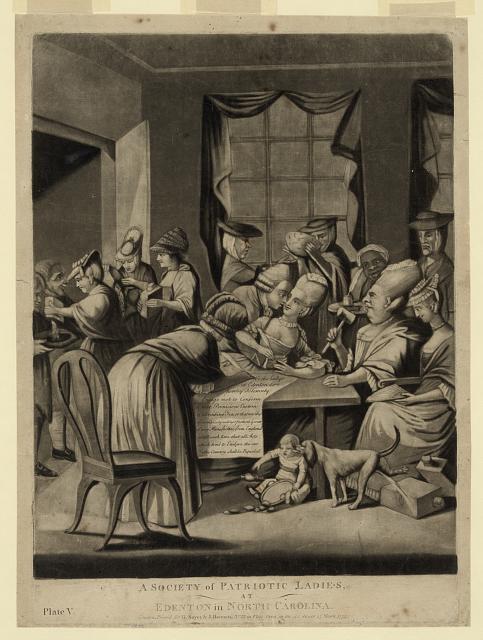

A society of patriotic ladies, at Edenton in North Carolina

This cartoon was produced to be a satire of women participating in the political action of boycott.

Women in colonial America and the early Republic were expected to be strictly domestically motivated. A woman’s role was to place the priorities of her husband, children, and home above all other things, including her own independence and autonomy. “Americans believed women to be innately domestic and endowed with the mission of caring for the home and maintaining the stability of the family.”[1] Not only were wives denied financial and legal autonomy from their husbands,[2] their intellectual independence was not even a consideration as women were expected to be satisfied and fulfilled by their domestic responsibilities. The domestic peace of the home was considered to be a haven for women against the chaos and “dirty politics of a man’s world.”[3] Women were simply expected to be obedient to their husbands and avoid the indelicacy of a public and political life.

The political and public realm was seen as only open to men. “Both men and women believed that it was right and proper for men to govern. Women were officially shut out from the polling place, from the legislative chamber, even from public discussions of political issues.”[4] Women who dared step into this realm via writing were often considered to be less than an ideal woman; to have lost their femininity. “Women’s loss of social value is figured … as a literal loss of beauty, social graces, and moral direction – their transgression supposedly marks their bodies and tarnishes their characters in socially recognizable ways.”[5] Some men even went so far as to believe that women who dared transgress in such a manner ought to lose their right to their own womanhood and all that entailed.[6] If, however, a woman had the audacity to speak in public about such matters, she was considered to have severely broken the rules and was supported by neither men nor even more progressive women.[7] For Mercy Otis Warren and Fanny Wright, would-be politically activated women, the stage was set for them to learn to abide by the rules or chance making their own.[8]

[1] Molly Abel Travis, “Frances Wright: The Other Woman of Early American Feminism,” Women’s Studies 22, no. 3 (1993): 390.

[2] Mary Beth Norton, Liberty’s Daughters: The Revolutionary Experience of American Women, 1750–1800 (Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press, 1996), 45–46 "Under the common law inherited from England, married women legally became one with their husbands, and so they could not sue or be sued, draft wills, make contracts, or buy and sell property”.

[3] Travis, “Frances Wright: The Other Woman of Early American Feminism,” 390.

[4] Rosemarie Zagarri, A Woman’s Dilemma: Mercy Otis Warren and the American Revolution (Somerset: Wiley, 2015), 22.

[5] Patricia F. Tarantello, “Insisting on Femininity: Mercy Otis Warren, Susanna Rowson, and Literary Self-Promotion,” Women’s Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 46, no. 1–4 (June 1, 2017): 181.

[6] Zagarri, A Woman’s Dilemma: Mercy Otis Warren and the American Revolution, 72" in an essay attacking the British feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, Timothy Dwight argued that women who wanted political rights‘ voluntarily relinquish the character and rights of women. Women, as such, have rights to tenderness, delicate treatment, and refined consideration. Men have no such rights. When women leave their character, and assume the character and rights of men, they relinquish their own rights, and are to be regarded and treated as men."

[7] RJ Connors, “Frances Wright: First Female Civic Rhetor in America,” College English 62, no. 1 (1999): 33 Despite supporting the futhering of women’s education “such midcentury English bluestockings as Hannah More, Elizabeth Montagu, and Hester Chapone” did not go so far as to suggest “that women should preach or be trained in rhetoric or oratory.”

[8] For an even broader discussion of women’s role during the early Republic see also Linda K. Kerber, Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America (Chapel Hill, UNITED STATES: University of North Carolina Press, 1980).