Fanny Wright’s biographer wrote that she “was loved and hated with equal extravagance.”[1] Wright’s most ardent support, and criticism, came during the years of her lecturing throughout the Northeast - 1828-1830. During her lecture series, she received no public backing and very little coverage from local newspapers, despite her lectures being thronged with enthusiastically cheering crowds.[2] “The most respectable citizens, almost without exception of class or sect, crowded to hear her; and in neither town could a public building be found large enough to contain those, whom a love of truth, or of novelty, or of both, collected on the occasion.”[3] Such glowing reviews of the crowds could not be found across the board. In 1838, the Cincinnati Chronicle contained an article which described the crowds as “mobs” and claimed that they had “disgraced the nation before the civilized world.” The article referred to Wright as the “high priestess of infidelity” and declared that through her lectures “many a happy home has been rendered a moral desert.”[4]

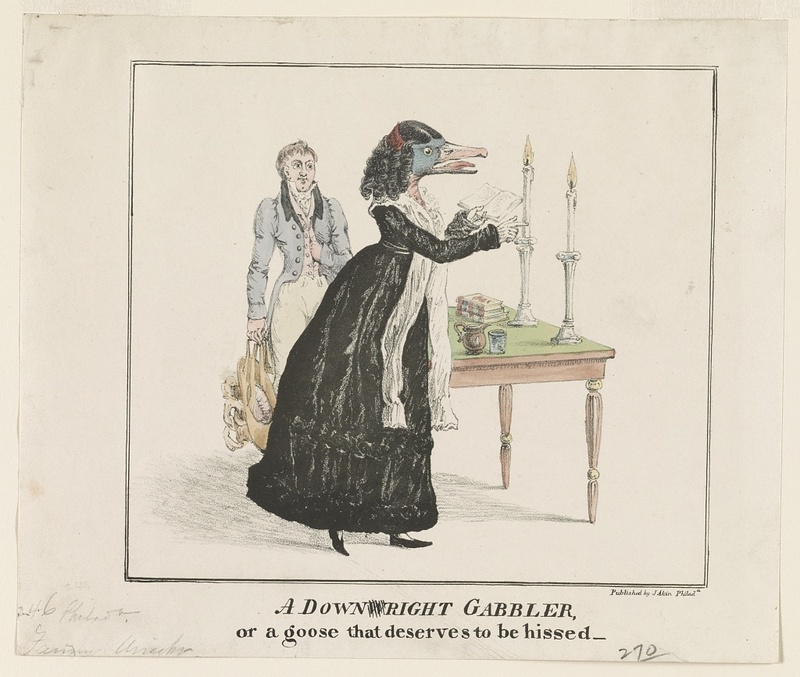

Despite the crowds’ enthusiasm, William Cullen Bryant, editor of the New York Evening Post, attended her first lecture and was affronted by her rejection of organized religion. He wrote afterwards that “for ourselves we confess that female expounders of any kind of doctrine are not to our taste. Aside from the incongruity of the practice with our notions of the proper sphere of their sex…there are other circumstances which go to render them unfit for being public champions of either side of a metaphysical controversy.”[5] Wright’s reputation found no quarter, even from other early feminists. Catherine Beecher, an activist and advocate for women’s education, wrote “who can look without disgust and abhorrence upon such an one as Fanny Wright.” She continued: “there she stands, with brazen front and brawny arms, attacking the safeguards of all that is venerable and sacred in religion, all that is safe and wise in law, all that is pure and lovely in domestic virtue…I cannot conceive any thing in the shape of a woman, more intolerably offensive and disgusting.”[6] Her views, particularly those against religion, categorized her as a radical. “ ‘Fanny Wrightism’ became the sobriquet for any position people wished to ridicule as extreme.”[7]

[1] Eckhardt, Fanny Wright : Rebel in America, 3.

[2] Eckhardt, 185–87.

[3] “Frances Wright’s Lectures,” The Free Enquirer, December 10, 1828.

[4] Cincinnati Chronicle, January 13, 1838. as quoted in Eckhardt, Fanny Wright : Rebel in America, 265.

[5] New York Evening Post, January 10, 1829. as quoted in Glicksberg, “William Cullen Bryant and Fanny Wright,” 427.

[6] Beecher, Letters on the Difficulties of Religion., 23.

[7] Connors, “Frances Wright: First Female Civic Rhetor in America,” 44.

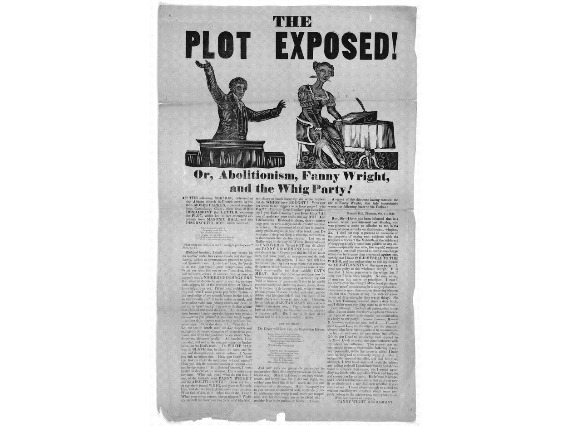

The plot exposed! or, Abolitionism, Fanny Wright, and the Whig party! The following sermon, delivered at the African church in Church Street, by the Rev. Moses Parkes, a colored preacher from Canterbury, Conn, drew from Miss Desdamont the letter

In this sermon, the Reverend declared that Fanny Wright had thrown off her abolitionist principles and sold herself to the Whig party, offering no help to the black slaves. In response, Fanny wrote to the Reverend denouncing his charges and declaring that "no man or set of men can buy me or my principles."