A 19th Century Perspective

Richard C. Mason’s dissertation serves as an excellent reflection on predominant theories surrounding menstruation. Rather than break his work down line by line, it is more productive to address the central musings. In doing so, a modern reader has a more grounded understanding of the material Richard C. Mason tackled alongside his own interpretations.

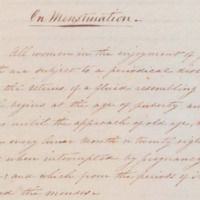

"All women in the enjoyment of good health are subject to a periodical discharge from the uterus of a fluid resembling blood, which begins at the age of puberty and continues until the approach of old age, recurring once in every lunar month or twenty eight days except when interrupted by pregnancy or lactation; and which from the periods of its return is called the menses."

Richard C. Mason presents menstruation as a natural phenomenon within a healthy female body. He thereby establishes a baseline of normalcy that guides the rest of his argument.

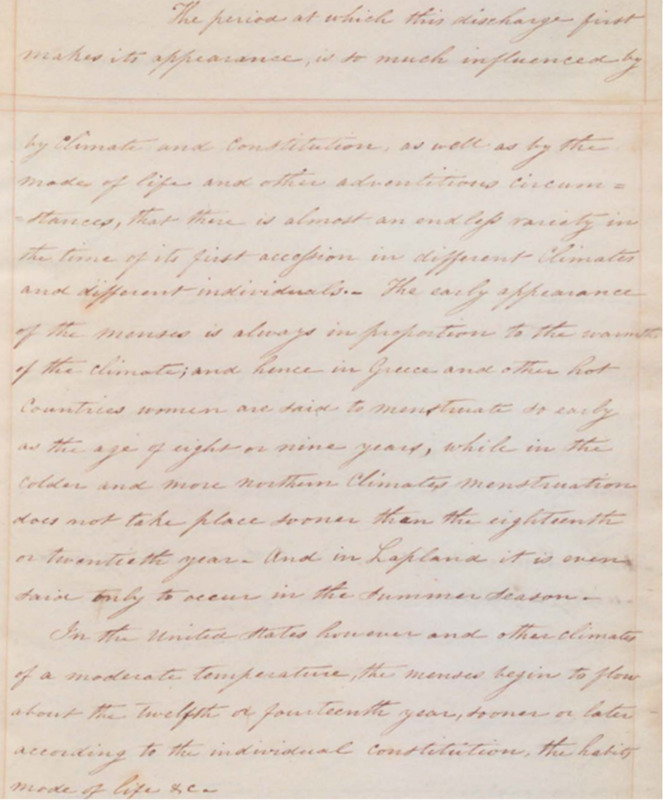

"The period at which this discharge first makes its appearance, is so much influenced by

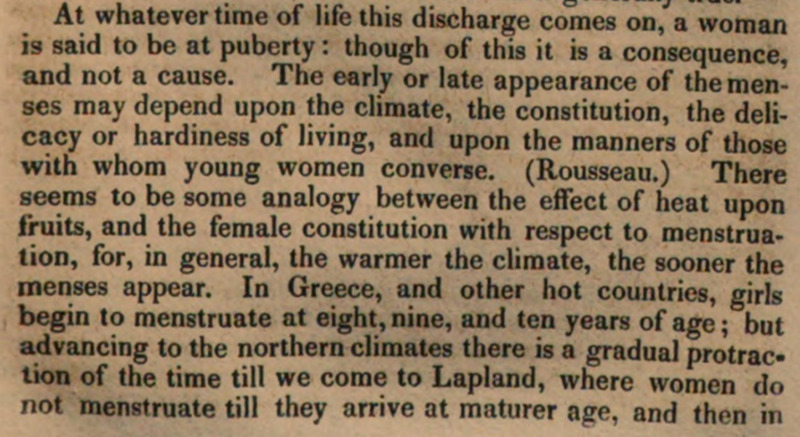

by climate and constitution, as well as by the mode of life and other adventitious circumstances, that there is almost an endless variety in the time of its first accession in different climates and different individuals. The early appearance of the menses is always in proportion to the warmth of the climate; and hence in Greece and other hot countries women are said to menstruate so early as the age of eight or nine years, while in the colder and more northern climates menstruation does not take place sooner then the eighteenth or twentieth year and in Lapland it is even said only to occur in the Summer season.

In the United States however and other climates of a moderate temperature, the menses begin to flow about the twelfth or fourteenth year, sooner or later according to the individual constitution, the habit, mode of life &c."

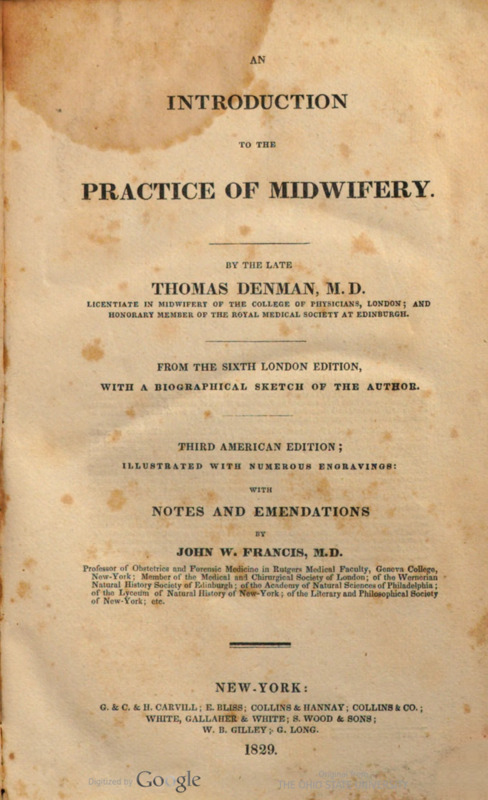

Temperature

The climate a woman is subjected to is of great interest to Richard C. Mason and the scholars he cites. Thomas Denman stands out in particular, and it is his theory of temperature that Mason readily adapts. Richard C. Mason reiterates his conclusions accordingly. In hot climates, one should assume that girls and women begin menstruation as early as eight years old. Conversely, in colder climates women are expected to experience the process in their late teens. Richard C. Mason takes this information and presents the idea that America, being more temperate, induces women to menstruate somewhere in their tweens.

The assumptions R.C. Mason draws on temperature is incorrect, but it provides additional context into how he may have understood maturity. It is at the start of menstruation that R.C. Mason declares a girl transforms into a woman. She is no longer affected by childish fancies and instead reorients to participate in the “female economy” of childbirth. Alone this outdated attitude is not necessarily alarming. Coupled with the knowledge that many enslaved people were taken from warm climates, however, one has to wonder how the above-mentioned theory shaped attitudes towards the maturity of Black girls. No definitive conclusion can be drawn on this matter, but it is important to keep in mind.

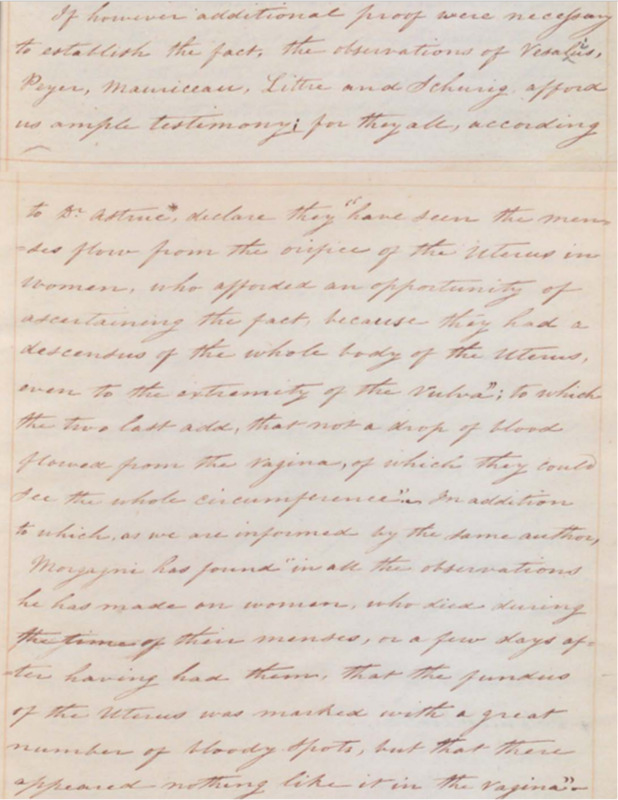

"If however additional proof were necessary to establish the fact, the observations of Vesalius, Peyer, Mauriceau, Littre and Schwig afford us ample testimony; for they all, according to Dr. Astruc*, declare they “have seen the menses flow from the orifice of the uterus in women, who afforded an opportunity of ascertaining the fact, because they had a descendus of the whole body of the uterus, even to the extremity of the vulva”; to which the two last add, that not a drop of blood flowed from the vagina, of which they could see the whole circumference”. In addition to which, as we are informed by the same author, Morgagni has found “in all the observations he has made on women, who died during the time of their menses, or a few days after having had them, that the fundus of the uterus was marked with a great number of bloody spots, but that there appeared nothing like it in the vagina”.

The Source

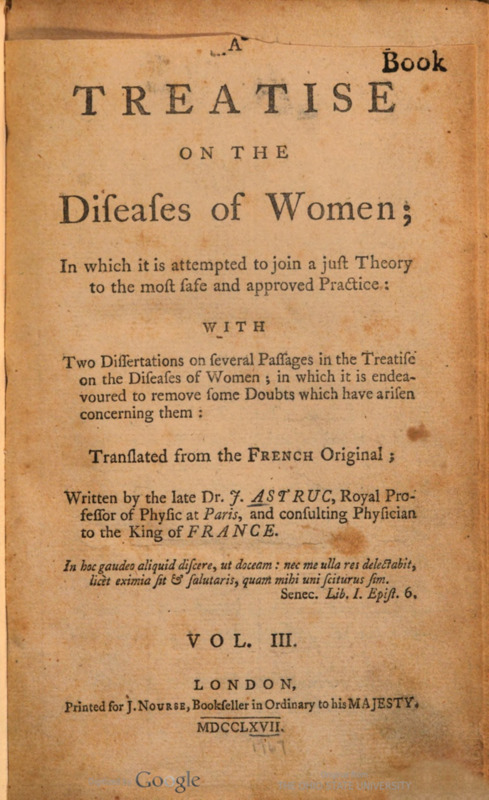

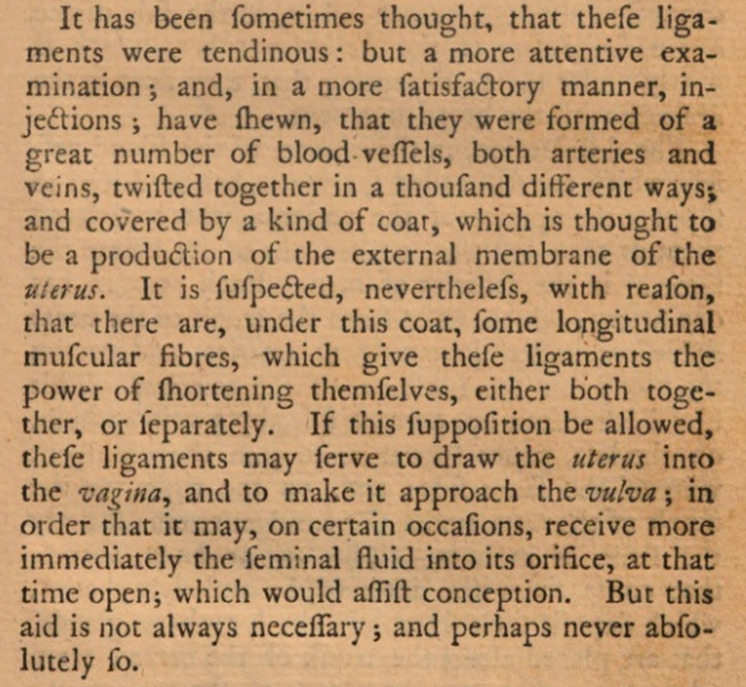

By the 19th century it is apparent to most students of medicine that the blood from menstruation originates in the uterus itself. The question medical experts continued to pose was whether it was distributed through veins or arteries. A Treatise on the Diseases of Women by Dr. J. Astruc is Richard C. Mason’s primary resource when delving into this topic. The fact that an American medical student would not only be aware of this French individual’s work but have access to its translation adds a trans-Atlantic dimension to Mason. The intellectual climate of 19th century America was one that intersected rather than developed parallel to European schools of thought. As to the question at hand, Richard C. Mason admits to being uncertain about the truth of the matter. He does suggest an alternative to what Astruc presents: discharge from menstruation neither comes from the veins or arteries, but vessels of secretory organs.

The reliance on corpses for scientific observation and research becomes evident at this point in the dissertation. Richard C. Mason himself factors their examination by his predecessors into his argument. This fact poses the very important question of whose bodies are being dissected as part of this larger debate on menstruation. These very bodies that make the intellectual exploration of the human body and its practical applications possible.

The Cause

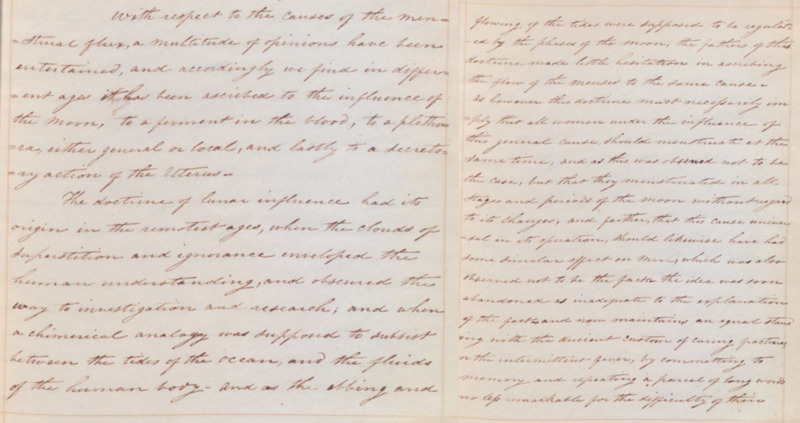

"With respect to the causes of the menstrual flux, a multitude of opinions have been entertained, and accordingly we find in different ages it has been ascribed to the influence of the moon, to a ferment in the blood, to a plethora, either general or local, and lastly to a secretory action of the uterus.

The doctrine of lunar influence had its origin in the remotest ages, when the clouds of superstition and ignorance enveloped the human understanding, and observed the way to investigation and research; and when a chimerical analogy was supposed to subsist between the tides of the ocean, and the fluids of the human body-and as the ebbing and flowing of the tides were supposed to be regulated by the phases of the moon, the fathers of this doctrine made little hesitation in ascribing the flow of the menses to the same cause. As however this doctrine must necessarily imply that all women under the influence of this general cause, should menstruate at the same time, and as this was observed not to be the case, but that they menstruated in all stages and periods of the moon without regard to its changes; and farther, that this cause universal in its operation, should likewise have had some similar effect on men, which was also observed not to be the fact the idea was soon abandoned as inadequate to the explanation of the fact."

The Moon

Perhaps the most ludicrous idea to the author, Richard C. Mason outlines an old theory connecting menstruation to lunar cycles. It also appears to be one of the most adaptable theories. Menstruation as fermentation of blood, plethora, or secretion have all been championed as the natural consequences of the moon’s influence. Yet Mason pushes back on this theory as mere superstition. He supports this position with the supposition that were women to be affected by the moon in this manner, they would all menstruate at the time. Richard C. Mason further argues that were the cause of menstruation so universal, men would also experience it.

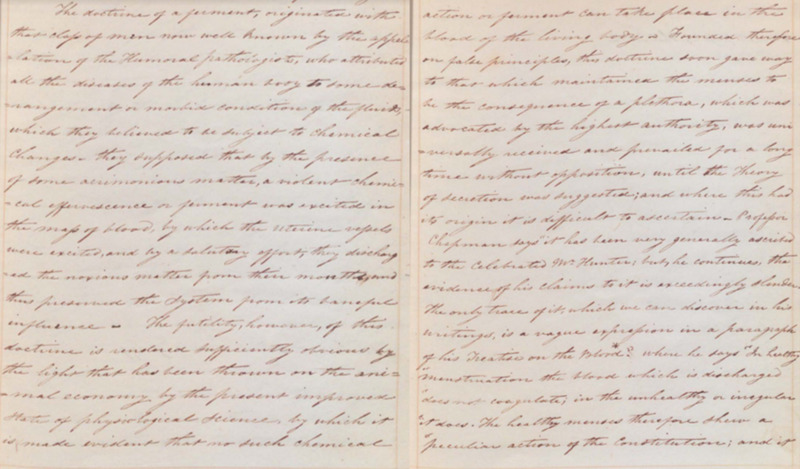

"The doctrine of a ferment, originated with that class of men now well known by the appellation of the Humoral pathologists, who attributed all the diseases of the human body to some derangement or morbid condition of the fluids, which they believed to be subject to chemical changes-they supposed that by the presence of some acrimonious matter, a violent chemical effervescence or ferment was excited in the map of blood, by which the uterine vessels were excited, and by a salutary effort, they discharged the noxious matter from their months and thus preserved the system from its baneful influence. The fertility, however, of this doctrine is rendered sufficiently obvious by the light that has been thrown on the animal economy by the present improved state of physiological science, by which it is made evident that no such chemical action or ferment can take place in the blood of the living body. Founded therefore on false principles, this doctrine soon gave way to that which maintained the menses to be the consequence of a plethora, which was advocated by the highest authority, was universally received and prevailed for a long time without opposition, until the Theory of secretion was suggested; and where this had its origin it is difficult to ascertain. Professor Chapman says “it has been very generally ascribed to the celebrated W. Hunter; but, he continues, the evidence of his claims to it is exceedingly slender. The only trace of it, which we can discover in his writings, is a vague expression in a paragraph of his Treatise on the Blood*.” where he says “In healthy” menstruation the blood which is discharged” does not coagulate; in the unhealthy or irregular” it does."

Plethora

The theory is plethora is one Richard C. Mason is quick to dismantle. He first establishes plethora with rival assumptions that women produce an abundance of blood or noxious chemicals. Menstruation, past experts have argued, is the body’s attempt to relieve itself of this excess quantity. Mason goes on to state that some medical professionals have theorized the inactivity of women in domestic spaces is the reason for why men do not suffer from a similar condition. The author dismisses this thought immediately on the basis that (presumably) working class women also experience menstruation.

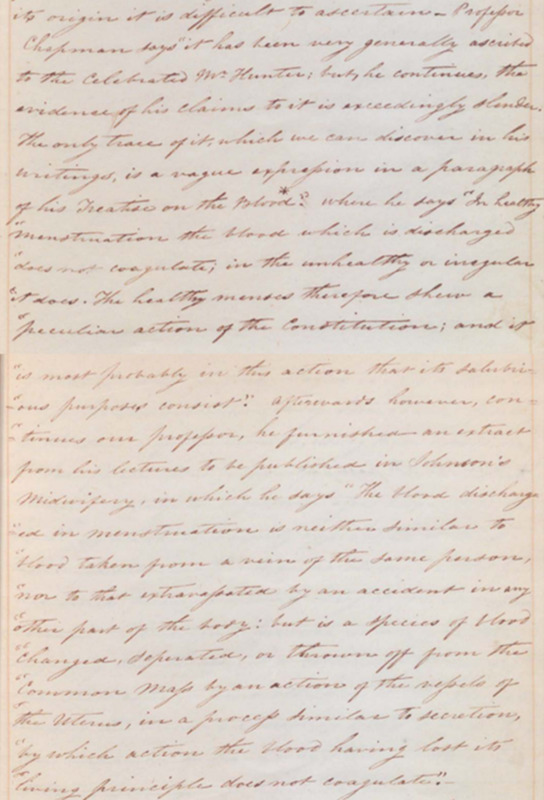

"Professor Chapman says “it has been very generally ascribed to the celebrated W. Hunter; but, he continues, the evidence of his claims to it is exceedingly slender. The only trace of it, which we can discover in his writings, is a vague expression in a paragraph of his Treatise on the Blood*.” where he says “In healthy” menstruation the blood which is discharged” does not coagulate; in the unhealthy or irregular” it does. The healthy menses therefore shew a “peculiar action of the constitution; and is “is most probably in this action that its salubrious purposes consist.” Afterwards however, continues our Professor, he furnished an extract from his lectures to be published in Johnson’s Midwifery, in which he says “The blood discharged in menstruation is neither similar to blood taken from a vein of the same person, nor to that extravassated by an accident in any other part of the body: but is a species of blood changed, separated, or thrown off from the Common Mass by an action of the vessels of the uterus, in a process similar to secretion, by which action the blood having lost its Curing principle does not coagulate.”

Secretion

Richard C. Mason cites two professors by the name of Chapman and James. He pulls from their own research to establish that menstruation discharge does not coagulate in the way blood is expected to. Building off of this basis, Mason asserts that the blood from menstruation is not the same as blood from a vein. It therefore cannot be the result of an overproduction of blood. Neither can this discharge be an attempt to expel bodily toxins, for by his logic men should have the same capabilities. Richard C. Mason instead argues that menstruation discharge is a secretion of the uterus that prepares it for conception. He satisfies the question of why men do not experience menstruation with this conclusion.

The culmination of Richard C. Mason’s argument firmly leads one to the topic of reproduction. The question that a modern reader would benefit from asking, then, is what relevance would menstruation and fertility have to a slave-owning, well-connected doctor? The answer is plenty. The post-colonial America that Richard C. Mason inhabited was still heavily reliant on slave labor. This labor replenished itself primarily through the reproductive process, and so the ability to understand it remained essential from an economic and professional standpoint. Medical knowledge of the 19th century messily intersected with the lives of enslaved people, particularly women, and the economic system that exploited them as a result.

Previous Next