William Lloyd Garrison's Conversion to Radical Abolitionism

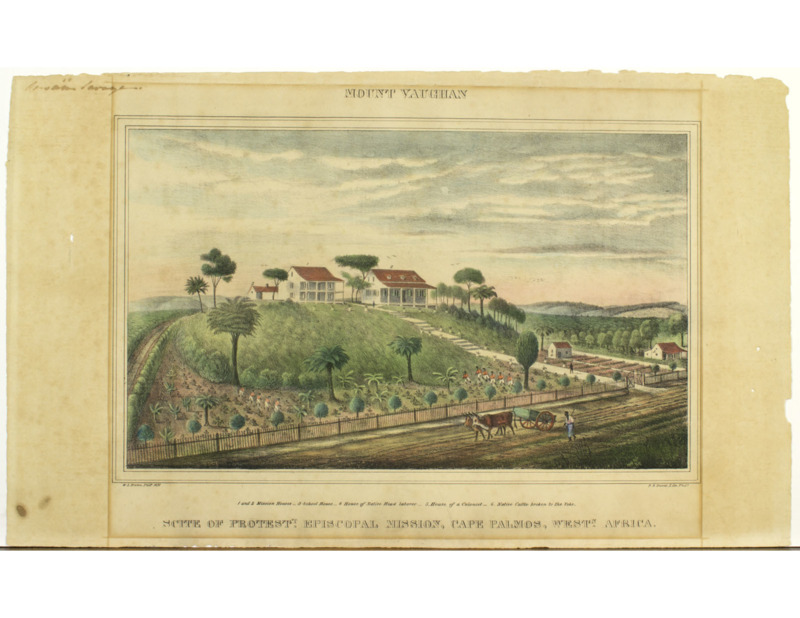

Mount Vaughan [graphic]: Site of Protestant Episcopal Mission, Cape Palmos, West Africa

View of the lush grounds of the mission begun in the black emigrant colony of Liberia in 1835 to educate and spread the gospel in Africa. Depicts the "mission houses," "school house," houses of a "native laborer" and "a colonist," and "native cattle broken to the yoke." A black man guides a cattle-drawn cart on the dirt road outside of the fenced mission fields where black laborers work. Begun under the auspices of the American Colonization Society and the Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of the Protestant Episcopal Church, the mission moved on March 4, 1837 to Mt. Vaughan, named in honor of the Missionary Society's Secretary of the Board, Rev. John Vaughan.

“If there be an institution, the direct tendency of which is to perpetuate slavery, to encourage persecution, and to invigorate prejudice, – although many of its supporters may be actuated by pure motives, – it ought to receive unqualified condemnation.”

William Lloyd Garrison, writing of the American Colonization Society in Thoughts on African Colonization

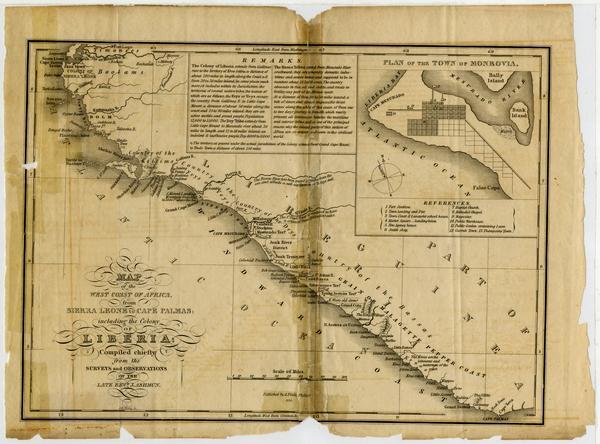

Shifting societal attitudes toward slavery, freedom, and liberty contextualized with Revolutionary war era rhetoric eventually persuaded northern state governments such as Massachusetts to pass gradual abolition laws. Once freed from bondage, however, African Americans in the North continued to face restricted prospects for participating as equal citizens in the United States. The American Colonization Society’s expressed goal to establish a West African colony in Liberia proposed to permit freed American blacks an opportunity to enhance the quality of their lives by bringing civilization and Christianity to their land of origin.[1] In the early decades of the nineteenth century, colonizationist belief that emigration resolved America’s race problem, alleviated the discrimination of freedmen, and offered slaveowners an incentive for emancipation, experienced mixed support from both whites and blacks. Over time, however, much of Boston’s black community, including David Walker, came to oppose the scheme, and committed themselves to staying in the land of their birth, fighting for their civil rights, and helping their fellow enslaved blacks out of slavery.[2] William Lloyd Garrison, associating himself with Boston’s black abolition leaders at the Liberator’s launch, gained a means to strategically distance himself from his prior objectionable support of colonization, by engaging with Walker’s and the black community’s antagonism toward it.

In his 2002 book, A Hideous Monster of the Mind, Bruce Dain tells us that current historical scholarship emphasizes the role that black intellectuals of the 1820s and 1830s played in convincing white abolitionists to adopt radical abolitionism. William Lloyd Garrison’s conversion from gradualism to immediatism, exemplified through his abandonment of the colonization movement, provides one such example of how black antislavery advocates like David Walker influenced broader perceptions about how to best execute abolitionist activism.[1] Although several years prior to launching the Liberator, Garrison expressed support for the American Colonization Society’s mission, similarly to Walker, Garrison came to understand the colonization scheme not as a means to gradually bring slavery to an end, but rather, to perpetuate the institution. In his 1832 publication, Thoughts on African Colonization, Garrison attacked the colonization movement’s logic on several fronts, most importantly, its conclusions about freed blacks’ inability to improve their degraded status on American soil. To expose white hypocrisy and fear regarding the capacity for freed blacks to inspire uprisings against the slavery system, Garrison held in Thoughts that the colonization movement conspired to emigrate freed blacks to Africa under benevolent pretense, “but really that the slaves may be held more securely in bondage.”[2] Demonstrating the validity of his conversion on the matter, Garrison goes on in Thoughts to cite several examples of his attempts to expose the ACS’ true motives in published articles over several early issues of the Liberator.

Garrison’s editorial choices also regularly provided space in the Liberator for black voices, for instance, the following letter to the editor from “A Colored Philadelphian,” published on February 3, 1831, which stated:

“I would also mention to the supporters of the Colonization Society, that if they would spend half the time and money they do, in educating the colored population and giving them lands to cultivate here, and secure to them all the rights and immunities of freemen, instead of sending them to Africa, it would be found, in a short time, that they made as good citizens as the whites.”[3]

Black readers of the Liberator acknowledged and cheered Garrison’s efforts to illuminate and strengthen their perspectives regarding colonization, inviting Garrison repeatedly to speak at black political meetings that gathered in dissent of the colonization movement. Garrison’s speeches continued common themes, present in both Walker’s Appeal and Garrison’s Liberator, that called for immediate emancipation, equal rights for African Americans, and the utter repudiation of the colonization movement. Garrison's conversion to immediatism, and his recognition of and engagement with the black-led radical abolitionism of David Walker and other black activists, endured for decades as Garrison's Liberator became a major force in the antebellum abolition movement.

[1] Dain, A Hideous Monster of the Mind, p. 153.

[2] “THOUGHTS ON AFRICAN COLONIZATION,” The Project Gutenberg eBook of Thoughts on African Colonization, by William Lloyd Garrison., accessed July 19, 2021, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/31178/31178-h/31178-h.htm, p.10.

[3] A, COLORED PHILADELPHIAN. "COMMUNICATIONS.: COLONIZATION HINTS." Liberator (1831-1865), Feb 12, 1831, 1, http://mutex.gmu.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.mutex.gmu.edu/magazines/communications/docview/91260793/se-2?accountid=14541.