Resistance

“During the summer of 1794, an enslaved woman named Kate petitioned George Washington with an unusual request. She wished to become a paid midwife “[to] serve the negro women (as a Grany) on [his] estate….”[1]

The False Lead

It is tempting to look at examples of enslaved women achieving “respectable” roles within an intellectual, slave-driven economy and call that resistance. While it was certainly an achievement, it is important to understand that these successes further profited slave owners and doctors like Richard C. Mason.Midwives are one such example. They actively participated in medical experimentation on Black individuals under the tutelage of doctors and other midwives.[2] Their pool of tutors was diverse, which granted these women access to knowledge normally distributed through formal institutions.[3] In this manner, enslaved women could cross racial boundaries and become integrated into a larger medical community. However the role of an enslaved midwife remained crucial to the slave economy, and midwives were afforded more financial and geographical freedom accordingly.[4]

Midwives ensured the successful reproduction of slaves while mitigating the loss of enslaved women during difficult pregnancies.[5] Their work made travel a necessity, and the freedom that came with mobility was a happy consequence of a privilege that could be revoked. Moreover, it was the responsibility of midwives to ensure enslaved women “...returned to work in a timely manner following childbirth.”[6] They were essential to keeping slaves productive above all else. This expanded the scope of midwifery, requiring them to take on even surgery in order to preserve the life of the mother and child.

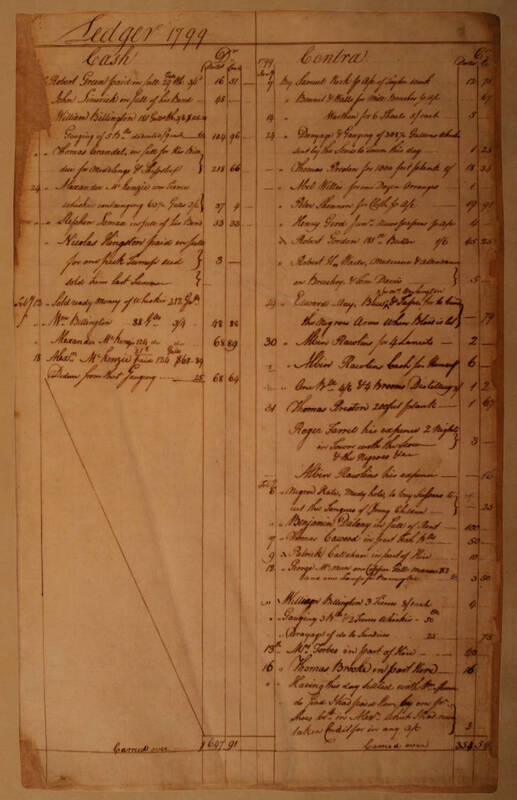

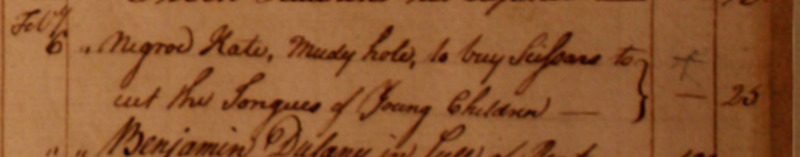

Cases of ankyloglossia or tongue-tie impede an infant’s ability to breastfeed;if left untreated, the infant will die due to a lack of nourishment.[7] A midwife was therefore required. She dispensed her surgical knowledge to correct this through a procedure known as frenotomy.[8] The frenotomy involved cutting the lingual frenulum with scissors or one’s fingernail, a necessary action often sponsored by one’s enslaver. George Washington is recorded to have given his own midwife, Kate at Muddy Hole, twenty five cents to purchase scissors for this very procedure.[9]

George Washington compensated Kate at Muddle Hole for her work, as was customary. Yet in 1797 Washington also petitioned Fairfax County for a tax exemption.[10] This woman who provided an invaluable service was declared unprofitable for his plantation on account of her age. One has to consider that midwifery itself was another means through which slave owners could extract labor from their elderly.[11]

Midwives achieved some financial and geographic autonomy for themselves due to their essential role, but this autonomy was allowed. Midwives were given special treatment within a slave society they continued to reinforce through their participation. They were widgets in the machine as opposed to its counterweight. The choices presented to enslaved Black women when it came to medical experimentation were tragically limited.

Appropriation

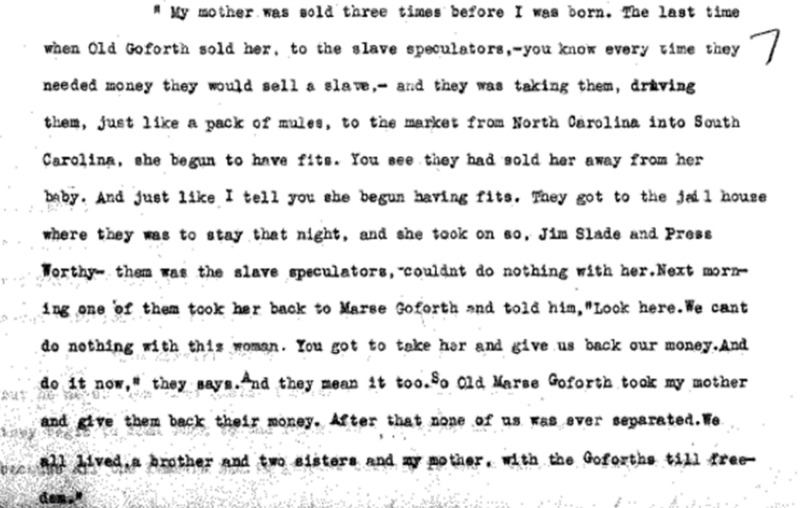

“Another enslaved woman named Wilmot at Fork quarter “always pretended to be too heavy [with child] to work and it cost me 12 months before I broke her.”[12]

When one’s body is a source of capital, choosing to become unproductive is a poignant means of defiance. This could easily take the form of malingering or feigning illness. The frequency with which it was utilized by slaves is debatable, but it was a suspicion that remained a significant concern for enslavers.[13] This is because true illness would hinder the capabilities of the slave while requiring prolonged, potentially expensive care.[14]

Despite the obvious investment in a slave’s productivity, doctors and enslavers alike were quick to deny trauma or abuse as contributing factors to illness.[15] This is particularly true in antebellum discourse on slaves who experienced epileptic fits.[16] In his own medical school thesis (1850), Moses D. McLoud of South Carolina discredited the obvious brain damage his slave endured after severe blows to the head.[17] He did so on the grounds that there was no swelling in the pupil, a requirement for prognosis that medical professionals themselves established.[18] Instead, McLoud asserted that slaves were prone to feigning concussions, epileptic fits, and other brain injuries.[19]

Trauma-induced illness, such as epilepsy, should not be dismissed. That said, malingering is still a possibility that provides greater insight between doctors, enslavers, and the enslaved. A fifteen year old slave named Virginia avoided both execution and the slave market in 1843, and this was accomplished after she had been diagnosed with severe epilepsy.[20] It is possible that Virginia, having been convicted with arson, made the calculated decision to save herself by taking advantage of contemporary, medical understandings of epilepsy and greatly diminishing her resale value. This theory is propped by personal testimony from the people who knew the subject, all of which suggest that she was as opposed to being sold as she was to execution.[21] This same testimony does not indicate that Virginia suffered from epilepsy after her court sentence either.[22]

The testimonies of former slaves indicate that they understood diseases like epilepsy in similar terms to the doctors that treated them.[23] Yet unlike the professionals that lorded over them, these same slaves acknowledged a link between physical trauma and epilepsy.[24] With this understanding came opportunity. These figures held close the possibility that slaves were appropriating medical dialogues[25] to reassert autonomy, escape work, and affect court decisions.[26] The very doctors who use Black bodies to inform their research then had to contend with slaves using them to further personal agendas.

“Slaves attempted to usurp control by exhibiting the terrifying and incurable physical condition of the epileptic fit, whereas masters attempted to maintain control by exposing their slaves' fits as phony and punishing the slaves for their imposture.”[27]

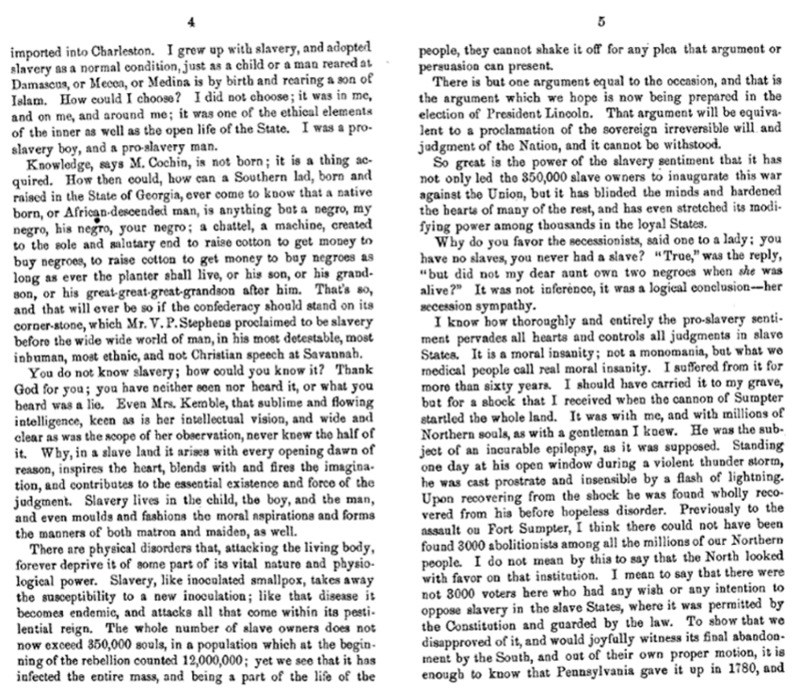

Anti-abolitionists were not shy in their appropriation of medical conditions to further their cause. Often they cited trauma-induced epilepsy as a chronic and devastating disability to highlight the cruel mistreatment of slaves, however these terms were also applied in comparisons for the sake of emphasis and allusion.[28] Charles D. Meigs is no exception. In his 1864 address to the Union League of Philadelphia, Meigs describes pro-slavery in terms of “moral insanity,” “epilespsy,” and “inoculated smallpox.”[29] Here, the association is clear. Slavery is something to be managed, then eliminated for the betterment of society. The technical language of doctors who support slavery, like Rochard C. Mason, is once again thrown back at them.

[1] Barbara Oberg, Women in the American Revolution : Gender, Politics, and the Domestic World (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2019), 19.

[2] Barbara Oberg, Women in the American Revolution : Gender, Politics, and the Domestic World (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2019), 21.

[3] Oberg, Women, 21.

[4] Oberg, Women, 26.

[5] Oberg, Women, 28.

[6] Oberg, Women, 28.

[7] Oberg, Women, 24.

[8] Oberg, Women, 25.

[9] Oberg, Women, 25.

[10] Oberg, Women, 30

[11] Oberg, Women, 30

[12] Oberg, Women, 30

[13] Boster, “An Epeleptick,” 289.

[14] Boster, “An Epeleptick,” 284.

[15] Boster, “An Epeleptick,” 284.

[16] Boster, “An Epeleptick,” 284.

[17] Boster, “An Epeleptick,” 285-286.

[18] Boster, “An Epeleptick,” 286.

[19] Boster, “An Epeleptick,” 286.

[20] Boster, “An Epeleptick,” 271.

[21] Boster, “An Epeleptick,” 287.

[22] Boster, “An Epeleptick,” 287.

[23] Boster, “An Epeleptick,” 288.

[24] Boster, “An Epeleptick,” 287.

[25] Boster, “An Epeleptick,” 291.

[26] Boster, “An Epeleptick,” 292.

[27] Boster, “An Epeleptick,” 291.

[28] Boster, “An Epeleptick,” 287.

[29] Charles D. Meigs, Address Delivered before the Union League of Philadelphia, Oct. 31, 1864 (Philadelphia: [Collins?], 1864), p. 4-5.