The Night Doctors

“Don’t you know the white man taught them all of that about ghosts. That was a way of keeping them down--keeping them under control.” [1]

Mrs. Smith, cited above, is just one of many Black informants whose testimony adds color to the complex, post-colonial tapestry that is American intellectual slave society. Black oral tradition remains a rich yet untapped resource for understanding the community’s widespread distrust of medical professionals. Night doctors. Student doctors. Ku Klux doctors. Night witches. Night riders. Though their names evolve, the dangers 19th century medical professionals represented remains constant.

The night doctor is one of several popular tropes in Black American narratives, dating it as far back as slavery itself.[2] It subjects the imagination to ruthless medical students and their coconspiratures prowling urban streets. Should they fail to steal cadavers from a fresh grave, these night doctors were thought to kidnap the unsuspecting for medical experimentation.[3] Supposed targets were the weak, old, drunk, infirm, disabled, and uniquely ill.[4]

What is especially important is the fact that the spread of this myth intensified as Black Americans migrated to urban centers.[5] This mass urban migration to the North, West, and South had a significant impact on the Southern economy, and so many Southern landowners discouraged it.[6] They circulated rumors about the fate of Blacks at the hands of Northern agents alongside the image of the night riders.[7] These night doctors became a staple of urban legends within Black communities as a result, with Sam McKeever standing as just one example of that fact.

“He sold his wife and didn’t know it. She had been carrying clothes and was sitting in the park. And he stole up there and throwed that mask on her. A big footed fellow like that. And then he got home and asked his children where their mama at. They said, “I don’t know.” Then it came to him what he had done, you see. He run to the doctors. She was breathing her last breath.” [8]

Sam McKeever was not the only bodysnatcher in Washington D.C., but oral tradition has preserved him as one of the most infamous.[9] Between 1880 and 1910, the Black rag seller became a boogeyman for his local community. The extent of his involvement in body snatching and the fate of his wife are subject to debate, given the natural offshoots that occur in oral storytelling, but what is certain is that this community was happy to be rid of him when he died.[10] Attached to the myth of night riders, McKeever was not a welcomed but rather threatening presence. This in itself is a testament to the real fear that Black Americans held towards doctors and the people who supplied them.

The methods Southern landowners employed to control the behavior of Black Americans were conceived in the preceding years of slaveholding. It is through her grandmother’s recollections that Mrs. Smith reanimates the image of overseers “riding through slave quarters covered in a white sheet, tine cans tied to his horse’s tail, in order to keep the slaves indoors at night.”[11] This behavior was not merely motivated by cruelty, but cold calculation as slave patrol systems were put in place to limit the unauthorized movement of Blacks. The men thereby became ghosts who quite literally haunted the steps of every enslaved individual walking the same paths as them. Their goal, of course, was to discourage slaves from gathering in groups and coordinating their escapes.[12]

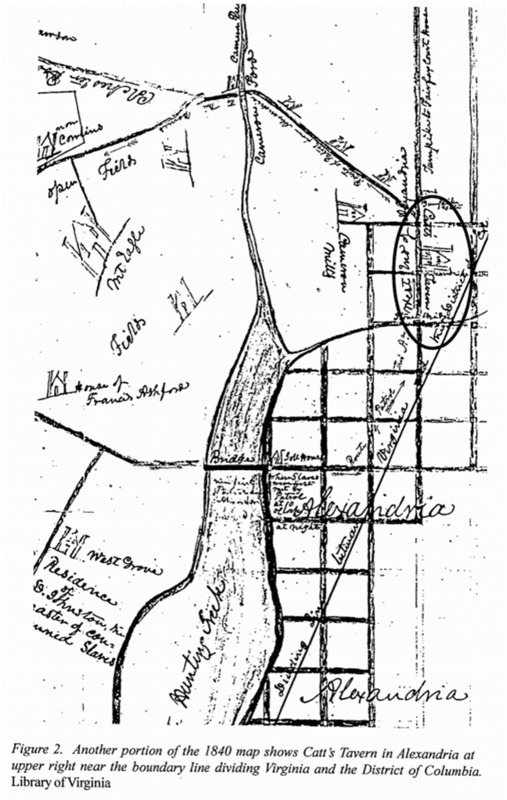

It’s unknown how intensely involved in the happenings of slave patrols R.C. Mason was. Though there is no indication that he joined them in harrying Black Americans in this particular incident, his participation nonetheless paints him as a sympathizer. In 1840, for example, he confirmed the testimony of patrolmen who had been assaulted in Fairfax County.[13]

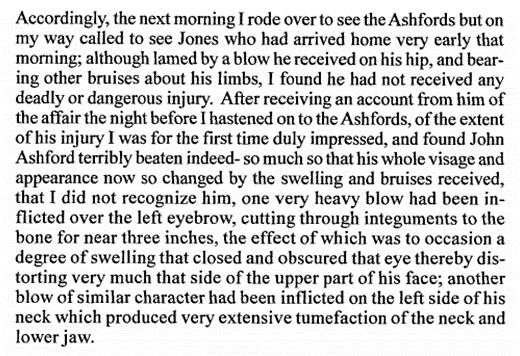

The patrolmen, a small group of four, were ambushed by Black slaves who proceeded to beat them terribly.[14] Richard C. Mason dictates to a court his involvement as the doctor that treated them, his account describing the injuries as “extensive” and the crime scene as “coated with blood.”[15] The language with which he describes both instances is concise and technical.

Richard C. Mason and his cousin, the committing Magistrate, then proceeded to defend the good character of the patrolmen themselves. This came in the face of pushback as some involved wondered whether the patrol was too harsh with the slaves in a previous encounter, therefore inciting such malignance.[16] Though Richard C. Mason and his cousin dismiss the claim on the grounds that the patrolmen were “the most intelligent and respectable men of the neighborhood,”[17] a modern reader should note that abusive slave patrols are prevalent in Black oral testimony.

“Willis Winn recalled an experience in which Klansmen made him dance and stand on his head: “I’s been cetched by them Ku Kluxers. They didn’t hurt me, but they have lots of fun makin’ me cut capers. They pulls my clothes off once and made me run four hundred yards and stand on my head in the middle of the road.”[18]

It is possible to draw several conclusions about Richard C. Mason within the context just provided. First, he carried the clout of someone with significant social standing. His own testimony props the narrative provided by the patrolmen, thus lending it additional credibility. With a relative serving as a Magistrate, one can assume that at least some of this influence stems from his own family position. Richard C. Mason’s profession as a doctor does lend him further respectability, however. His testimony enjoys an extra layer of professional expertise, for Richard C. Mason was “qualified” to assess the condition of the patrolmen injured. His conclusions of those injuries and the crime scene itself, abundant with blood, plays a role in the flow of the court case that follows the ambush.

Readers should also understand that Richard C. Mason’s sympathies lied with the patrolmen rather than the enslaved people who beat them. Richard C. Mason is an authority figure, and the patrolmen are his neighbors. As a slave owner whose profession is also so deeply intertwined with slavery, he has every motivation to reinforce the power structures in place during an intellectual slave-driven economy. The patrolmen could not be guilty of mistreatment, for there were no official complaints filed against them. They could not have deserved the brutality, as they were upstanding citizens.

Without the counterweight of Black oral tradition, one might be inclined to accept Richard C. Mason’s attitude. Though the “ghosts” that imbedded themselves into Black narratives were not real, the bodily threat their inspirations posed to enslaved persons were. In a similar vein, the mythological image of a murderous medical student was likely just that. A myth. What it represented was the very real entitlement of medical professionals to Black bodies. Thus, white slave owners and their Southern, land-owning successors as the original culprits for the night doctor myth.

A Doctor’s Entitlement

“In several instances physicians purchased blacks for the sole purpose of exper- imentation; in others the doctors used free blacks and slaves owned by others.” [19]

Living subjects were sometimes acquired by universities The legal procurement of corpses was impossible in the 19th century, and so many universities sponsored the illegal purchase or outright theft of bodies.[20] This became something of an open secret, as universities who successfully avoided the ire of angry relatives and friends rarely faced the punitive wrath of city authorities.[21] The bodies of slaves, the poor, and the otherwise vulnerable became the primary targets of universities as a result. In extreme cases, some Black Americans were even killed.[22] This continued to occur despite the rise of racial theory, interestingly. Though intellectuals were asserting the medical differences between different races, the day-to-day teaching and research practices reflected the opposite.[23] With the realization that Black bodies were useful for medical experimentation comes the question of agency.

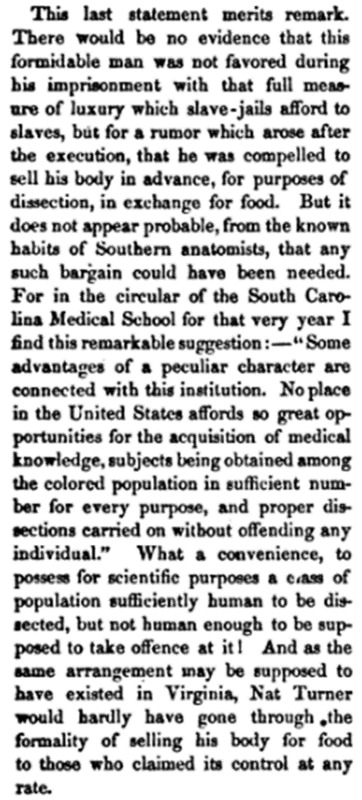

The rebellious Nat Turner found himself similarly exposed to the doctor’s knife when captured and imprisoned in a state jail. He had been, allegedly, coerced into signing a release in exchange for food.[24] In doing so, Turner gave doctors permission to dissect him post-mortem. His own lack of agency is itself a testament to the contentious relationship between doctors and Black Americans, however the reaction to the rumors that he was coerced is equally informative. An 1861 issue of the Atlantic Monthly, for example, went out of its way to dispute the rumor as a fabrication. Its justification as to why remains concerning to a modern reader nonetheless.

According to the Atlantic Monthly, featured to the right, the doctors of the South Carolina Medical School did not need to coerce Nat Turner into signing over the rights of his body. They were amply supplied subjects by the “colored population” already.[25] The source goes so far as to identify advertisements sponsored by the medical school of the time. Note this is just one of many, and that these advertisements are an open admission to past academia’s interest in slave experimentation. This is a merited assumption, for universities offered reduced rates to slave owners regarding the treatment of ill slaves.[26] These factors persuasively argue that Black bodies, dead and alive, were considered valuable research tools for doctors.

Race and Class

“...the bodies of coloured people exclusively are taken for dissection, 'because the whites do not like it, and the coloured people cannot resist." [27]

The climate of the 19th century made it possible for Black bodies to end up on the dissecting tables, operating amphitheaters, classrooms, and experimental facilities dedicated to medicine.[28] This fact should neither be downplayed nor discounted when one considers the other victims of medicine. Transient, poor, and foreign white bodies were also subject of experimentation. This is largely due to class narratives, however, which determined whether one was respectable enough to constitute as the “correct” variation of whiteness.

Irish immigrant women in particular were not afforded a reputation of modesty, and so they were cast with the same racist stereotype that haunted Black women: unabashed, carnal desire.[29] Medical research sought to reinforce this, of course. Irish immigrant women were therefore left vulnerable to exploitation by medical professionals. The same hole in the safety net extended to poorer white women and those who had crossed social boundaries by participating in interracial relationships.[30] Class becomes intermingled with race, then, as opposed to a parallel reason for exploitation. The poor, the rebellious, and the non-white were all some variation of social outcast that allowed doctors easier access to them. It allowed Richard C. Mason to have easier access to them as well. Though it cannot be determined whether he himself held experimented on individuals, the research he used for his dissertation was acquired within that environment.

[1] Gladys-Marie Fry, Night Riders in Black Folk History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 171.

[2] Fry, Night Riders, 171.

[3] Fry, Night Riders, 171.

[4] Fry, Night Riders, 190.

[5] Fry, Night Riders, 172.

[6] Fry, Night Riders, 172.

[7] Fry, Night Riders, 172.

[8] Fry, Night Riders, 204.

[9] Fry, Night Riders, 202.

[10] Fry, Night Riders, 205.

[11] Fry, Night Riders, viii.

[12] Fry, Night Riders, 171.

[13] Edith Moore Sprouse, “Outrage Near Spring Bank: Slave Resistance in Fairfax County,” Yearbook: The Historical Society of Fairfax Country, Virginia 29 (January 2003): 100.

[14] Sprouse, “Outrage,” 99.

[15] Sprouse, “Outrage,” 106-107.

[16] Sprouse, “Outrage,” 111.

[17] Sprouse, “Outrage,” 111.

[18] Fry, Night Riders, 147.

[19] Todd L. Savitt, "The Use of Blacks for Medical Experimentation and Demonstration in the Old South." The Journal of Southern History 48, no. 3 (1982): 342.

[20] Fry, Night Riders, 176.

[21] Savitt, “The Use of Blacks,” 337.

[22] Fry, Night Riders, 176.

[23] Todd L. Savitt, "The Use of Blacks for Medical Experimentation and Demonstration in the Old South." The Journal of Southern History 48, no. 3 (1982): 332

[24] Fry, Night Riders, 176.

[25] “Nat Turner’s Insurrection,” Atlantic Monthly, 8 (Aug. 1861), 185.

[26] Fry, Night Riders, 176.

[27] Todd L. Savitt, "The Use of Blacks for Medical Experimentation and Demonstration in the Old South." The Journal of Southern History 48, no. 3 (1982): 337.

[28] Todd L. Savitt, "The Use of Blacks for Medical Experimentation and Demonstration in the Old South." The Journal of Southern History 48, no. 3 (1982): 331

[29] Savitt, “The Use of Blacks,” 115.

[30] Savitt, “The Use of Blacks,” 115-116.